Some actors transcend the characters they play. Some become so familiar to us that no matter the effort we make, it is impossible to suspend disbelief, to see the performance before the performer. Such is the price of fame, at least from the perspective of the audience. As an example, think of Al Pacino’s portrayal of Ricky Roma in Glengarry Glen Ross. An incredible performance from a legendary American actor, seething with Pacino’s own brand of exuberance. That role, however, was where Pacino slipped into type. Moviegoers no longer see the characters he plays. They see Al Pacino, which is not necessarily a bad thing.

In a biopic, however, such a close identification with a star can mean that the focus of the film, the person whose life was so compelling Hollywood felt the need to intervene, can become lost behind the performance. The makers of biopics end up having to walk a fine line, making choices about who is more important, subject or star. More importantly, it is the actors themselves who must decide on their own whether to let their talent overshadow the great figures of history.

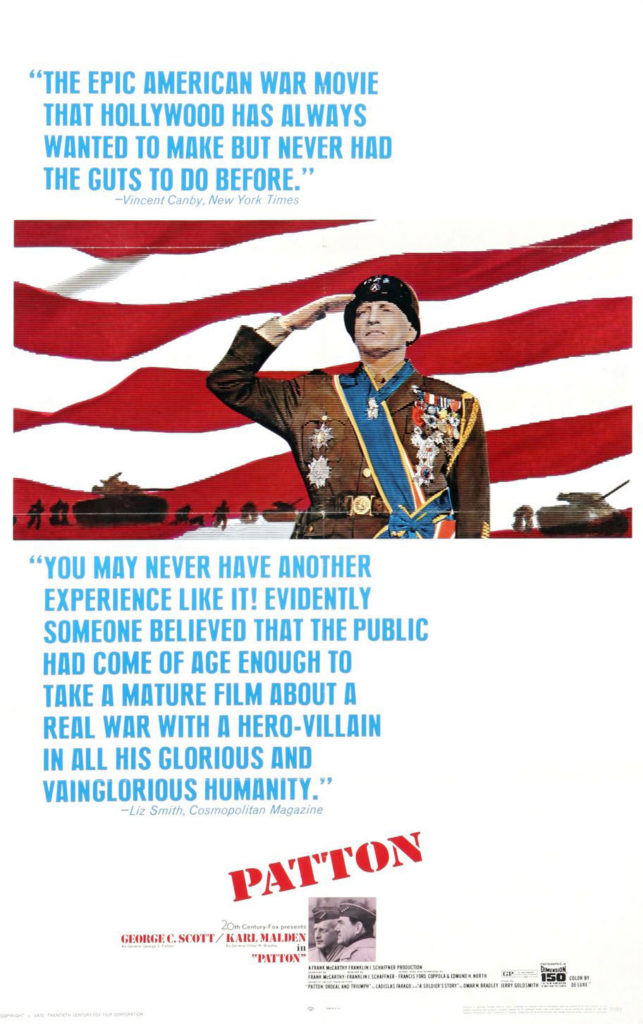

So there is the conundrum. In 1969’s Patton, which is more important, the larger than life figure of General George S. Patton, or the larger than life performance of George C. Scott playing Patton? Caesar himself or the play? It’s a false choice, really, when Scott so effectively becomes the man.

Scott won an Oscar for this performance, and famously declined the honor. Not because he didn’t feel his acting was up to snuff, but because he didn’t feel competition among actors was right. But no matter his motivations, his performance was indeed worthy. His  portrayal of Patton is his signature role, the first line in his obituary. Not Bert from The Hustler, or Buck Turgeson from Dr. Strangelove, regardless of their respective excellence. Patton.

portrayal of Patton is his signature role, the first line in his obituary. Not Bert from The Hustler, or Buck Turgeson from Dr. Strangelove, regardless of their respective excellence. Patton.

The film opens with a medal bedecked Scott in front of a towering American flag backdrop delivering an animated address to the unseen soldiers of his command. Brutish, foul-mouthed, confrontational, also subdued and reverent, this speech informs the viewer within the first minutes of a long film that Patton is not just a man of passion, but is governed by fierce emotions. He is a man whose entire life has been spent preparing for this moment. And what a moment. World War II. War’s greatest stage. History’s most tragic era. There could never have been a more opportune time for Patton to have stars on his shoulders. He believed it was his destiny.

Scott captures all of Patton’s well-known characteristics, with the exception of the general’s voice. Apparently, Patton had a strangely high-pitched voice, the one thing about him that didn’t seem large. Scott as Patton growls when he talks, gravel transforming into boulders when he roars. It works.

Besides Patton as leader and tactician, Scott channels the rest of the man. All of him centered on war, but there was also a poet...who applied war to his verse. And a student of history...who studied war. And a mystic who believed in reincarnation. Of course, he believed he was a general in his previous lives. Patton was brash and blunt, with a mouth as perilous to his own person as his generalship was to our enemies. All of it Scott makes his own.

Patton follows the general’s service in the war from when he took command of II Corps in Africa after their spectacular defeat at the Kasserine Pass in 1943, and finishes with his leaving 3rd Army in peacetime Europe after the war’s conclusion. The film plays fast and loose with the facts, but it is a movie. I have yet to see a scholarly book of history, politics, science, etc., that has ever listed a movie in its footnotes. Three hours is not enough time to compress three years of a very busy life, but the filmmakers managed to squeeze the major anchor points, if somewhat paraphrased, into the story.

Designed more to entertain than inform, Patton does its job well on the backs of Scott, and Karl Malden, who played General Omar Bradley. In real life and on the screen, Bradley is Patton’s counterweight. Humble to contrast with Patton’s bombast, Bradley at times also acts as Patton’s conscience. In the scenes they share, Patton becomes as much the story of two generals as one. But why have two generals, when you can have three?

Apparently the Nazis weren’t enough of an adversary for Patton, so the filmmakers play up a rivalry with Britain’s Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, played by Michael Bates. He plays Montgomery with the perfect amount of pettiness and ego. While there is an effort at times throughout the film to build this rivalry into the central focus of the plot, Patton has his own mass and gravity, and there really isn’t enough room for another Herculean, yet rodomontade, warrior.

As for this rivalry’s accuracy, one sequence, where Patton has a cavalier attitude towards his soldiers’ lives in racing Montgomery to Messina during the Sicily campaign, is fiction. Patton and Montgomery were in no race to rob each other of personal glory. Such behavior would have been abhorrent. Having read multiple histories of the war (but admittedly not the works cited in the credits as sources) that make no mention of such a ghastly competition, I have no reason to believe that it occurred.

Scott dominates the film, but behind him is a well-crafted epic with some good acting in important roles, and some mediocre acting in bit parts. Many of the locations are expansive. Even when they are not, director Franklin J. Schaffner manages to make a handful of tanks feel like an armored battalion. There’s a fair amount of sap to contend with, and were it nor for Scott, and Malden, many of the clichés would prevent Patton from being a great film. Don’t look for Patton to delve into the morality of war too deeply, either.

The battle scenes are what one would expect from a movie almost four decades old. Wounds are rare, exploding shells leave soldiers dead, but intact, and there isn’t that much blood. No matter, though. The film doesn’t suffer from its lack of battlefield realism. War was Patton’s great desire. For the audience, fulfillment is reached simply by watching Scott.