Apocalypse Now dropped into my cinematic experience like a bomb. When I was a teenager, I had been vaguely aware that it was a film about the Vietnam War, but I thought nothing more about it other than that it had an interesting title. I had seen other Vietnam War films, notably Platoon and Full Metal Jacket, and felt like I was familiar with the material I would see in Apocalypse Now, so there was no great rush on my part to seek it out. Also, there wasn’t anyone my age (somewhere in the early years of high school, I’m not exactly sure when) who had seen it, so there weren’t any peer recommendations or condemnations to go with the film.

I first saw Apocalypse Now at my father’s house in Philadelphia. I was digging through the tapes in the television cabinet looking for something to watch and came across a home recording of the film taped off of the Movie Channel sometime in the early 1980s. I asked the old man if the movie was any good and he gave me the astonished look of the learned man suddenly confronted with ignorance in a place he had not known it had previously existed. It was getting close to midnight, and Apocalypse Now is a long film, but my father insisted I put the tape in the VCR, crank up the volume through the stereo, turn the lights off, and sit back. To add to the drama, he went upstairs to bed, leaving me alone with the film, like some cinematic equivalent of a young Indian brave going on his first vision quest. It was overdramatic, but I played along.

The tape was grainy and dark, the result of it being cheap consumer stock, and shelf-bound for a decade, but on the screen the opening scene dissolved in from black. A green, monochromatic expanse of jungle tree line stretched beyond the breadth of the camera, swaying back and forth in slow motion. There were brief glimpses of helicopters flying past in the foreground, heralded by the noise of their rotors, slowed and distorted, made to sound as they would if a chopper could fly through molasses. The opening strains of The End by The Doors began to play, and when Jim Morrison began to sing, the jungle exploded in napalm and fire. Apocalypse Now was about a minute old at that point and it was unlike anything I’d ever seen.

Through the weirdness of that first scene,  after the jungle dissolves into a very close and personal setting with Martin Sheen descending crazily into a bottle of brandy, to the tragicomic melding of Wagner and Colonel Kilgore, to the acid soaked wretchedness of the ghetto soldiers thrown mercilessly into the shit at Do Long, to the final half hour of bizarre company with Marlon Brando, I was rapt, wide-eyed at what I was seeing, body and mind thumped by the deep blows of every explosion that came through the speakers, and every piece of synthesized mayhem in the music that Carmine Coppola composed for his filmmaker son’s study in controlled chaos.

after the jungle dissolves into a very close and personal setting with Martin Sheen descending crazily into a bottle of brandy, to the tragicomic melding of Wagner and Colonel Kilgore, to the acid soaked wretchedness of the ghetto soldiers thrown mercilessly into the shit at Do Long, to the final half hour of bizarre company with Marlon Brando, I was rapt, wide-eyed at what I was seeing, body and mind thumped by the deep blows of every explosion that came through the speakers, and every piece of synthesized mayhem in the music that Carmine Coppola composed for his filmmaker son’s study in controlled chaos.

Francis Ford Coppola once said famously about his film that it was not about Vietnam. It was Vietnam.

“We were in the jungle, there were too many of us, we had access to too much money, too much equipment, and little by little, we went insane.”

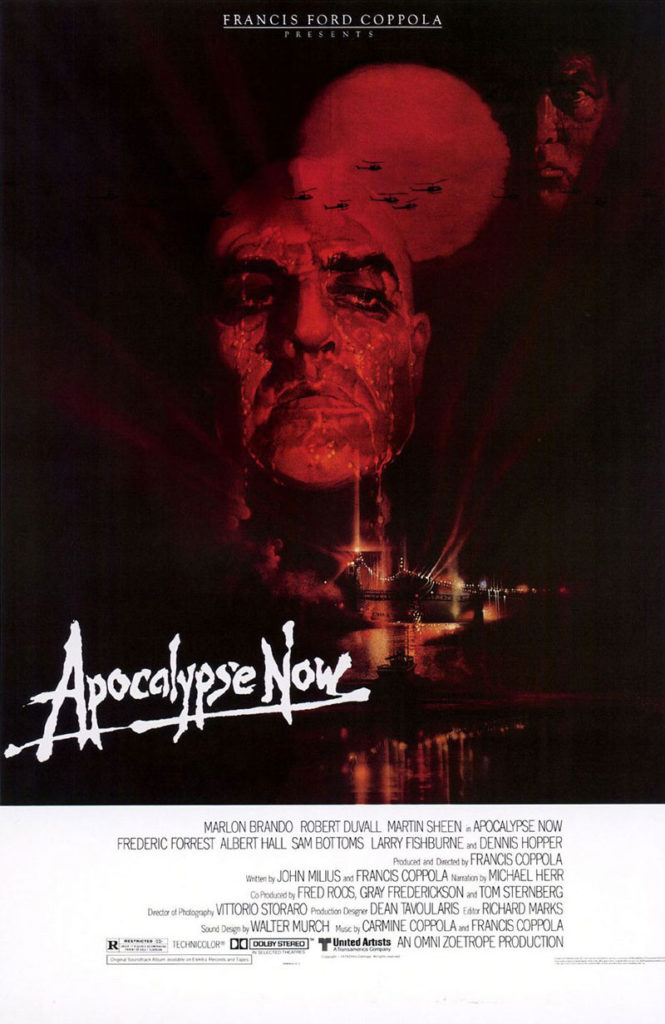

It took him more than a year of filming in the jungles of the Philippines, standing in nicely for South Vietnam and Cambodia, to finish principal photography. During that time he fired the original star of the film, Harvey Keitel, and replaced him with Sheen, who almost died from a massive heart attack a year into filming. Another star, Marlon Brando, arrived on set obese (although he was playing a green beret), and completely uncooperative, insisting on rewriting or improvising his scenes. Entire stretches of shoot were ruined by typhoons and wretched locally based French actors. The production ran out of money, forcing Coppola to commit all of his assets to the film’s production. Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. All of this and more acted as barriers to completing possibly the most complicated project ever put on film.

Production took so long that the film was dubbed Apocalypse When? by many in Hollywood before its release. Finally, in 1979, three years after cameras began to roll, it was shown at Cannes, winning the Palme d’Or. Apocalypse Now was Coppola’s personal hell, much of it his own creation. It’s small wonder he attached such significance to its production when, broadly considered, it did mirror the war it was about.

Apocalypse Now is adapted from the Joseph Conrad novella Heart of Darkness. The setting has been moved from turn of the 20th century Belgian Congo to 1960s war torn Southeast Asia. The Congo River has been replaced by the fictional Nung River, and the Belgian trading company employees have been replaced by the U.S. military.

Captain Willard (Sheen) is a special forces soldier, an assassin, recently returned to Vietnam for a second combat tour after finding himself unable to adapt to his return to the world. He waits in a dingy Saigon hotel room for a mission and is given one, which he refers to, as part of excellent narration written by Michael Herr, as “...a real choice mission. And when it was over, [he’d] never want another.”

Willard is tasked with traveling up the Nung in a navy patrol boat into Cambodia, locating a rogue special forces colonel named Kurtz (Brando), and killing him. It’s an insane mission for an insane war, and an insane idea for a story about our military, but times have changed. Vietnam was traumatic for our country, far more so than Iraq has been. Trust in our leadership was destroyed by the war. The Vietnam War was far more public and bloody, and we could see in the faces of the dead every day, and in the stellar efforts of the era’s war correspondents, just how much we were being lied to by generals and men in suits. By contrast, the bad times in the Iraq War were far less bloody and far less visible. We have, by conscious decision of those in charge, been kept at arm’s length in Iraq. The public nature of the Vietnam War soured the public on it so thoroughly that while outlandish, the idea that an army colonel could be targeted by his own was actually regarded as plausible in the 1970s.

The small boat in which Willard undertakes his journey is populated by one officer, Chief Philips (Albert Hall); and three draftees, Lance (Sam Bottoms), Chef (Frederic Forrest), and Clean (Laurence Fishburne). They’re all green, even though a couple have been in country for some time. One gets the idea that Willard is the only person on the boat who has any inkling of what war really means. Willard certainly seems to think so, but as the journey progresses it becomes clear that even Willard hasn’t seen war like this.

On his way to confronting Kurtz, Willard sails through a menagerie of the war’s horrors. One of his first encounters is a village destroyed, in order to save it, by a battalion of airmobile infantry. It’s there that he meets Lt. Colonel Kilgore, played by Robert Duvall.

Kilgore is a cartoon warrior. Gung-ho, focused, lethal, and wrapped so thoroughly into the insanity of the war he doesn’t realize how far away from humanity he’s gone. He’s bold, loud, loves to blow stuff up and lives by the doctrine of overwhelming force. He never stops to consider if what he is doing is right, or even whether it is working. He has a mission and is incapable of finding flaw in it. His one introspective moment is capped by the phrase, “Someday this war’s gonna end.” That’s it. No prediction about winners or losers, just that the killing will one day stop. It’s the only crack we see in Kilgore’s façade — as close as he ever gets to doubt. Kilgore acts as allegory for America itself. He represents American excess and ignorance. He understands nothing and destroys everything.

In fact, every stop that Willard makes on his journey upriver plays like a visit from one of Dickens’ ghosts from A Christmas Carol. Instead of showing Willard the folly of his ways, however, these encounters confront him and the viewer with America’s follies. Willard sees ridiculousness and absurdity everywhere the American military machine treads. He witnesses a foolish effort to bring American pop culture to the deep jungle in the form of Playboy bunnies. He sees the absurdity of shooting, then offering help to those who have been mortally wounded by our bullets. Willard and the crew find themselves in a wretched place, next to a bridge across a river that is blown up by the enemy every night, and rebuilt by the Army everyday, an epic illustration of pointlessness.

Finally, after Willard, and the viewer, have been presented with a scathing picture of war, we reach journey’s end, and meet the conscience of America in the form of Colonel Kurtz.

Kurtz is the one man, though insane, who understands the war. That knowledge itself is what drove him over the edge. He’s seen what Willard, Kilgore, and every other soldier in Vietnam have seen. More importantly, he has seen what the generals and politicians haven’t. But he can’t reconcile what he has seen with what he knows is right. He can’t equate the myth of America with its actions, actions he himself engaged in. His response has been to rebel, in mind, spirit, and how he fights the war. And he is still fighting, almost as if it’s all he knows how to do. But now he follows the rules of the jungle, not those invented under fluorescent tubes half a world away. Kurtz has stripped away all lies and delusions from war and what he has done. Consequently he has been stripped of all comfort, and is left the very personification of guilt, as ruthless in his introspection as he is with death.

At this point, Willard is only sure of one thing, and that is he had no idea what to expect of Kurtz. Once again, it’s another part of the journey the viewer shares with Willard. After two hours of accompanying Willard upriver it’s impossible to predict what Coppola has planned. He wasn’t all too sure, either, until he filmed it. For many viewers, the entrance of Kurtz is when Apocalypse Now descends into cinematic overindulgence. For others, myself included, after seeing and listening to Kurtz, there is nothing else that could have been waiting for Willard. There is man and monster; man made into monster, in fact, by his experiences. There is no doubt that Kurtz is, indeed, insane. But sentencing him to death for it...The man is as much victim as beast, and there is no way to envy Willard for the decision he has to make.

With Apocalypse Now Coppola presented the first silver screen indictment of our involvement in Vietnam. American filmmakers have always been at their best when they turn the mirror towards the country, and Coppola is no exception. One of the things that continues to keep Apocalypse Now so powerful is its honesty. Its message hasn’t been distorted by the lens of time, or the ready dismissal of culpability we have ascribed to the Iraq War. Lately, our perception of the Vietnam War has been colored by our latest misadventures, upgrading a clear losing effort in the jungle to at worst, defeat because of lack of fortitude. Those who fought in it are heroes again. All the blood spilled, washed away. In watching Apocalypse Now, it becomes impossible to forget that for a decade, it was the entire nation on that boat with Willard, and it was we who lost our minds in the jungle.

In 2001 Coppola released Apocalypse Now: Redux, an updated cut of the film with over an hour of excised footage restored. Like many director’s cuts or special editions, Redux makes clear that there was a reason the footage was on the cutting room floor in the first place. But at least he resisted the temptation to spruce things up with CGI effects.

There’s also a five-hour long work print floating around on the internet. This cut is strictly for the curious only. It’s a cut made with temporary score and unmastered sound before it was handed off to Walter Murch for editing. It’s interesting as a peek into how Coppola was picturing the final product.

For insight into the shooting process itself, Coppola’s wife Eleanor filmed much behind the scenes footage, and this footage was incorporated into the documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. It’s a great companion piece to the film in the same way Burden of Dreams is to Fitzcarraldo.

There’s at least one more person that deserves mention, and that is cinematographer Vittorio Storaro. Apocalypse Now was shot beautifully, and Storaro is responsible for that. Perhaps the most striking sequence he shot was a nighttime bombing raid. It was spectacular, and the entire sequence was cut from the film. It was restored as backdrop to the end credits on some 35mm prints, and on television release versions, so I saw this sequence the first time I saw the film. Coppola cut the scene because audiences regarded it as a continuance of the ending, whereas Coppola didn’t want that impression to be made. It’s a haunting sequence shot with multiple frame rates scored with abstract music by the Grateful Dead’s Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann. The sequence is included as an extra on DVD releases.