In 1998 Peter O’Toole played Dr. Timothy Flyte in Phantoms alongside Ben Affleck, Liev Schreiber and Rose McGowan. I love it when fine actors slum it. One can read just how closely their patience is being tested on their faces. Oh? Filming my part is going to stretch longer than a week? My apologies, but I must be on a flight back to England by Friday. What’s that? You have more money? I would be delighted to stay!

I bring up Phantoms not to slam O’Toole for chasing a paycheck. I bring it up because the man was only in his mid-sixties when that film was made. Watch the film, though, and you see the face of a man much older. That was nothing new for Peter O’Toole. He always had the presence and bearing of a man older than his true age. It was a combination of acting skill, personal attitude, and the ravages of alcohol that allowed him to play above his age when he needed to. A dash of makeup here and there, a bit of grey in the hair, and a 35-year old O’Toole slips easily into the role of a 50-year old king. Put in a less roundabout way, the now retired Peter O’Toole was a versatile actor. He displayed this in a unique way by playing the part of England’s King Henry II in two different films made in the 1960s four years apart, but taking place approximately a decade and a half apart.

In one, Becket, he plays Henry in his mid-thirties. In the other, The Lion in Winter, Henry is fifty. Fifteen years is a long time in a person’s life. Sure, the years begin to fly by the older we get, and it seems as if we settle into a static, unchanging existence at some point, but that’s false. Any glance at old pictures from fifteen years ago should be enough to disabuse a person of the idea that they are the same person they were back then. The accumulation of small changes is imperceptible on their own, but taken cumulatively, they seem to grow exponentially the more time passes. My point is, Peter O’Toole was such a skillful actor that he seemed to have no trouble playing Henry at different stages in his life. It had to have helped that the two films are unrelated productions. There was no need for continuity between the two performances.

More people than can be counted have  portrayed the same character in multiple films, sometimes at quite different stages in that character’s life, but it’s fairly uncommon for that to happen in films that have little to nothing to do with each other. A couple examples come to mind. Paul Newman played “Fast Eddie” Felson twice, twenty-five years apart. Although The Color of Money could be considered a sequel to The Hustler, the distance in time and filmmakers sets it apart. Sean Connery played an older James Bond in a non-Eon production, Never Say Never Again. That had the added weirdness of being a remake of Thunderball, which also starred Connery!

portrayed the same character in multiple films, sometimes at quite different stages in that character’s life, but it’s fairly uncommon for that to happen in films that have little to nothing to do with each other. A couple examples come to mind. Paul Newman played “Fast Eddie” Felson twice, twenty-five years apart. Although The Color of Money could be considered a sequel to The Hustler, the distance in time and filmmakers sets it apart. Sean Connery played an older James Bond in a non-Eon production, Never Say Never Again. That had the added weirdness of being a remake of Thunderball, which also starred Connery!

Both of these examples showed actors revisiting characters after a good deal of time had gone by in the real world, but O’Toole went back to Henry II after only four years, and had to act his way through the aging. It’s only one of the things that made both performances a bit special.

Becket, adapted from the play Becket ou l’honneur de Dieu, tells a highly fictionalized version of the true conflict that arose between Henry II and Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, which led to Becket being assassinated inside Canterbury Cathedral. Much of the real life slow build in the conflict was expunged for dramatic expediency, and some whoppers were told to explain Becket’s actions in the film. Obscure to modern viewers, the Norman conquest of England established a dichotomy of class between the native Saxons and the conquering Normans. In the film, Becket is portrayed as a Saxon who harbors inbred resentments against the Norman King Henry, despite their friendship. It makes for some overblown drama in the film, but in real life, Becket was also a Norman. Well, there goes much of the justification for the drama of the film.

Who’s a Norman and who’s a Saxon doesn’t really much matter to this American. Luckily, while there’s a lot of Saxon-this and Norman-that, the viewer can discount all that nonsense. The incident that sets Henry and Becket against each other is not an ethnic conflict, but a religious one. Oh boy.

In the film, Henry maneuvers to have Becket, his closest adviser, appointed Archbishop of Canterbury, because Henry fears the growing power of the Catholic Church in England. Politically, it’s a brilliant move, and appears to neuter any church opposition to Henry’s rule. But then one of Henry’s Lords arrests a priest and has him killed. This was more than a breach of etiquette in Medieval England. Once upon a time, the Catholic Church reserved the right to arrest and try its clergy in their own courts, making them, in effect, above the law of the king. Becket, having become, in a sense, born again after taking on the Archbishopric, chooses to take Henry to task over the killing, and their friendship dissolves into threats and, in the end, violence.

The film was made right on the cusp of aesthetic changes in filmmaking. It’s long, and has the air of being an epic tale, even though it’s a little close in for that. The sets are all bright and colorful, quite sanitary in appearance, and there’s an overabundance of loud horns in the soundtrack. It’s all supposed to be very profound and regal, but it makes the film look dated.

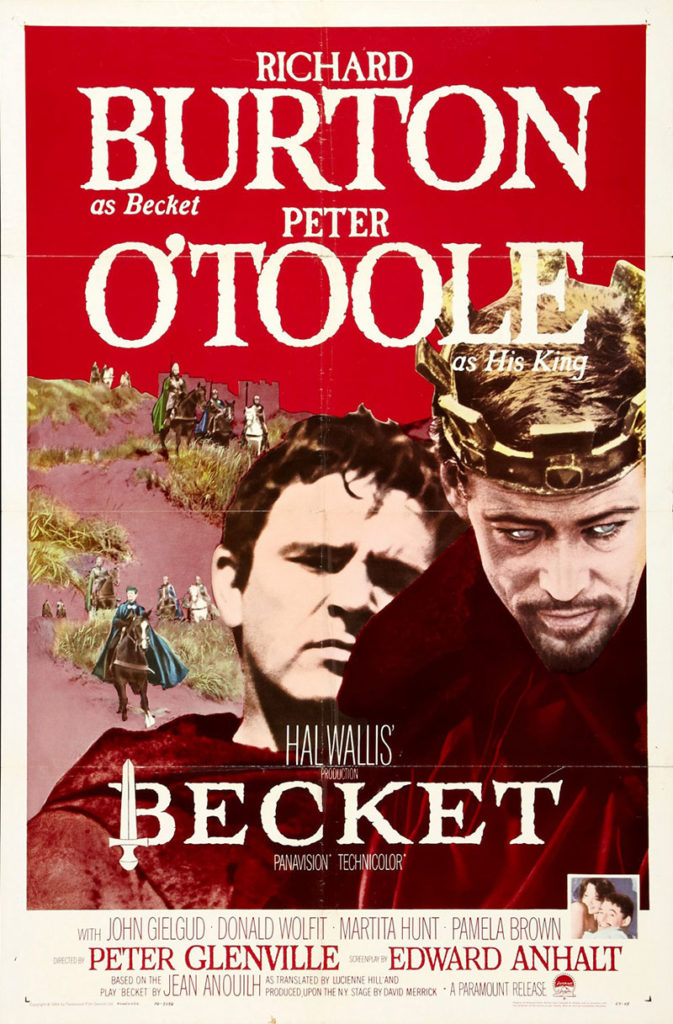

Luckily, the performances of the two leads make nitpicking the production irrelevant. O’Toole was joined in the film by Richard Burton as Becket. He delivers a typically stern performance, one that conveys Becket’s sincerity. It is good Burton’s acting was able to do that, because Becket’s sudden piety seemed to be thrust on him by nothing but a change of clothes. His intensity was important, as both Becket defying Henry, and Burton playing off of O’Toole, required strength in the character.

O’Toole gives a bit of a shouty performance, but even when he doesn’t resort to this technique, he commands every scene he’s in. Medieval kings were notoriously egotistical, something about being chosen to rule by God, and they could never, ever take second to anyone else in the room. Such behavior today would seem boorish, maybe even abhorrent, but for a king it was essential. And anyone who complained would regret it. O’Toole goes so far that he seems to make everyone in scenes with him very nervous. If none of the supporting cast was directed to act that way, then bravo for Mr. O’Toole — he played kingly intimidation to its proper level. If they were directed to act so, it certainly doesn’t take away from O’Toole’s uncomfortable exuberance.

Despite its length, Becket moves along swiftly enough. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s a must-see classic, the story being a bit thick and the enormity of the production being off-putting, but O’Toole was nominated for an Oscar in this one for a reason.

He was also nominated for playing Henry in The Lion in Winter, adapted from a play by the same name. Rather than exploring ethnic and political intricacies spanning many years and reaching many countries, The Lion in Winter is the story of the Christmas family get-together from hell.

Henry is in the winter of his life, how clever, and has summoned his Queen and his sons to his castle for Christmas. Unlike any other family that faces tension when they gather for the holidays, these five central characters sometimes seem intent on killing each other. A cursory examination of history shows that, when it comes to royalty, killing each other is what they sometimes did.

Even during the holidays the family can’t set their intrigues aside. And why should they? Henry is old. His reign will soon be coming to an end. Each of the players has an interest in his successor. Besides Henry looking to secure his legacy, is his wife, Eleanor of Aquitane (Katherine Hepburn). She’s more than just an estranged spouse. She has been imprisoned by Henry for her machinations in trying to depose Henry from the throne.

This lovely pair have three surviving sons: Richard (Anthony Hopkins), Geoffrey (John Castle), and John (Nigel Terry). Each of them wants to succeed Henry, and each has their own plan. Richard and John have an ally in Henry and Eleanor, respectively, leaving poor Geoffrey the odd child out, but he manages to create his own mischief.

The film is all about the scheming and interplay among the family members. It’s such a relentless and petty, vindictive spat, that were it not for the scale of the hate, and the ever-present prize that is England, it would be easy to forget the losers may end up with their heads separated from their shoulders. And there is where the differences between a simply dysfunctional family and a Medieval royal family lie. At the head of it all O’Toole’s Henry commands the room, as he did in Becket, but this older Henry is clearly wearying of the role, recognizing it’s all a game that must be played. Stop, and he dies.

“I’ve snapped and plotted all my life. There’s no other way to be alive, king, and fifty all at once.”

So says Henry, and no other line encapsulates the film.

The entire film is full of witticisms and insults as well written as that line. James Goldman adapted his own play for the screen, and his screenplay has quite a bite to it. Whether it’s O’Toole screaming at his sons, or Hepburn delivering deadly insult after deadly insult to her king, it never lets up, and it’s engrossing. One could almost feel pity for these people, as their only escape from this razor’s edge is death. There is no true victory. After all, Henry is king, and he is just as trapped as the others.

The performances from the featured players are quite good, although Nigel Terry went too far with John’s bumbling simplicity. To be honest, his performance seemed more suitable for a Monty Python sketch parodying the film, but c’est la vie. He’s in it, and that’s that.

O’Toole and Hepburn had the greatest pedigree among the cast, and it shows. The scenes they share together are intimate and brutal. The viewer sees an actress that is a long way from the flat ingénue that Dorothy Parker once lambasted.

This was also Anthony Hopkins’s first film. He was already thirty at the time it was made, so much of the rough edges were smoothed out working in theater. Having reached stardom after his youth was passed, it’s surprising to see him in such a physically intimidating role. He carries himself like a centurion.

His prince is the brute of the three, John of course being the idiot, while Geoffrey is the sneaky manipulator. Maybe if all three were united, they could do battle with Henry, but separated, they are nothing. Henry fully realizes this, and the climax of the film comes when it appears his lies, cajoling, promises, rebukes, and manipulations drive all three sons away.

The production is markedly different from that of Becket. The polished nature of that film has been expunged for dirty floors covered in thrushes, and mangy dogs seemingly everywhere. Elegant, this vision of a Medieval castle, it is not. This makes the film feel a bit more real than it should, which is a good thing. We’re watching a play on film, only superficially expanded from the constraints of the stage. It’s small in all the right places, whereas Becket tried to be large in all the wrong places.

Christmas with the Angevins is serious business, and makes for a lively film. The best part is a viewer doesn’t need to know a damn thing about history for this film to be accessible. Just know that it’s a king, a queen, and three rotten sons trying to work out who will be the next King of England. Sit back and enjoy the show.