Baron Victor Frankenstein is back. At the end of the previous film, The Evil of Frankenstein, the series’ antihero was dispatched along with his box-headed creation. It was a scene of ultimate finality, even if there wasn’t a shot of a dead Frankenstein putting an exclamation point on his story. But death is never permanent in film should the producers wish it. I don’t just mean the death of a character, either, but the actor who plays the part. This film’s star, Peter Cushing, finds his character resurrected for further use in this film, but Cushing himself was resurrected digitally, more than twenty years after his death, to make an appearance in the latest Star Wars flick. It won’t be much longer before actors find themselves under the same threat of obsolescence as the rest of us in the workforce. But I digress…

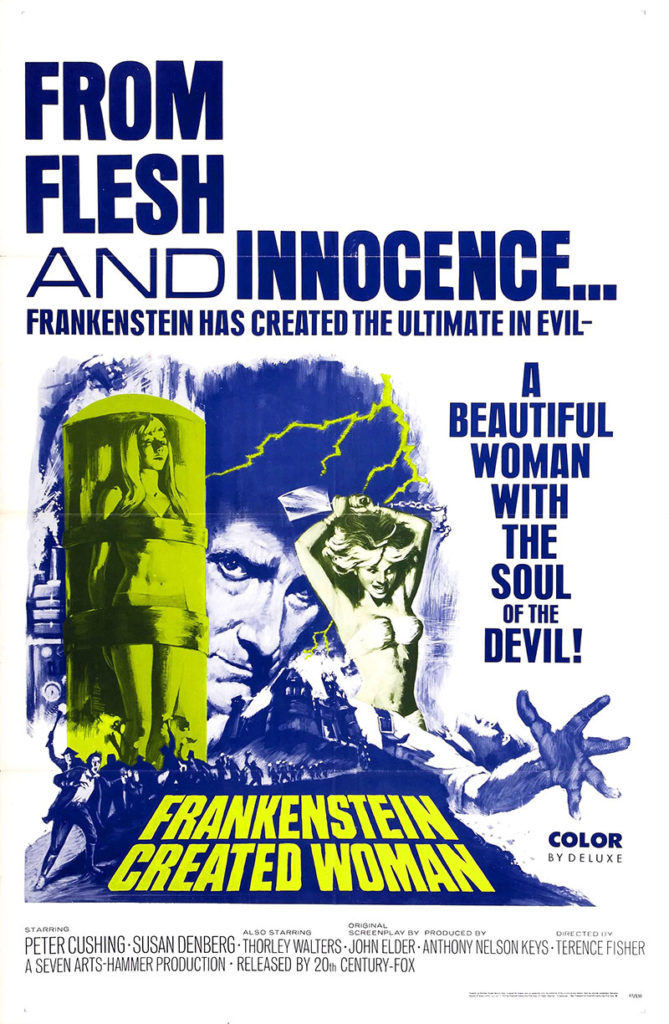

From 1967, Frankenstein Created Woman is the fourth entry in Hammer’s Frankenstein series. Directed by the immortal Terence Fisher and written by Anthony Hinds, the film finds Frankenstein again with a new lab in a new city full of people who are creeped out by Frankenstein’s mysterious nature. He also has a new assistant, aging town doctor Hertz (Thorley Walters), who, for reasons unknown, has decided to spend his retirement aiding Frankenstein in his efforts to perfect human resurrection. Frankenstein’s methods are a bit different in this film.

Unlike the previous film, this film ditches the similarity to the Universal Frankenstein films, and returns to producing more original ideas. Frankenstein isn’t just cobbling together parts anymore. Through experimentation, he has discovered that he can remove and hold the soul of a deceased individual, and place it in another, whole, body. Much of the film’s science concerns the soul, in fact, which makes it poor science, but it’s fine for a movie. If a movie can bring the dead back to life, who am I to quibble with its poor understanding of neuroscience? It is just a movie, after all. And this film’s purpose is to entertain, not inform.

A trio of spoiled aristocrats, led by the loathsome Anton (Peter Blythe), finds joy in tormenting a local innkeeper (Alan McNaughtan) and his daughter, Christina (Susan Denberg). Another of Frankenstein’s assistants, the poor peasant Hans (Robert Morris), who smitten with the lovely but disfigured Christina, takes exception, and violence ensues. Honor is defended and all that. But later in  the evening Anton and company decide to wrap up their night with a little murder, returning and killing the innkeeper, for which Hans is blamed. Justice is swift and brutal. Hans loses his head. Christina witnesses the execution, and distraught at seeing her lover perish, ends her own life by jumping into a river. How tragic. But not for Frankenstein! That guy is always in need of bodies to carry out his experiments, and now he has two.

the evening Anton and company decide to wrap up their night with a little murder, returning and killing the innkeeper, for which Hans is blamed. Justice is swift and brutal. Hans loses his head. Christina witnesses the execution, and distraught at seeing her lover perish, ends her own life by jumping into a river. How tragic. But not for Frankenstein! That guy is always in need of bodies to carry out his experiments, and now he has two.

I don’t know what, exactly, he thought he would accomplish by cramming two souls into a single body, but that’s what he does. Along the way he also gives Christina’s body a makeover, and we see that not only did Frankenstein create woman, he created sexy woman.

Like Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, the last film I reviewed for this month, Hammer crammed some clumsy sex into this movie. Before her brief forays into film, Denberg had been a Playboy Playmate in 1966. Fisher and producer Anthony Nelson Keys took advantage of this, but still couldn’t bring themselves to show a nipple on screen.

What follows is a revenge film. No bumbling creature, this. Christina is awake, whole, and with an extra soul who is pretty pissed at losing his head.

It was wise for Hammer to return to its own ideas when it came to Frankenstein. The people involved in these films have always felt more like craftsmen than true artists, but when they did have an opportunity to stretch their wings creatively, it has usually paid off, especially for the writers. It’s still a Frankenstein film, though. By that, I mean the core elements are the same. Frankenstein will resurrect a dead person. That dead person will show some promise, at first, of fulfilling Frankenstein’s dream of perfecting eternal life, but then the killing starts. It’s a pattern as reliable as that in the Mummy or Dracula films. But what makes this series more engaging than the other two is the writers, with the exception of The Evil of Frankenstein, have been better at switching up some of the details.

Also, Cushing has always been good in his role. The character of Frankenstein has gone through metamorphosis, as Hammer has altered his backstory from film to film. But whether he was called upon to play Frankenstein as stubborn, insane, vengeful, or compassionate, Cushing did the job well. He is Frankenstein.

Frankenstein Created Woman is one of the better Hammer flicks I’ve seen this month, owing to Cushing, a decent screenplay, and a care shown in the production that has been lacking in some of the other Hammer films.