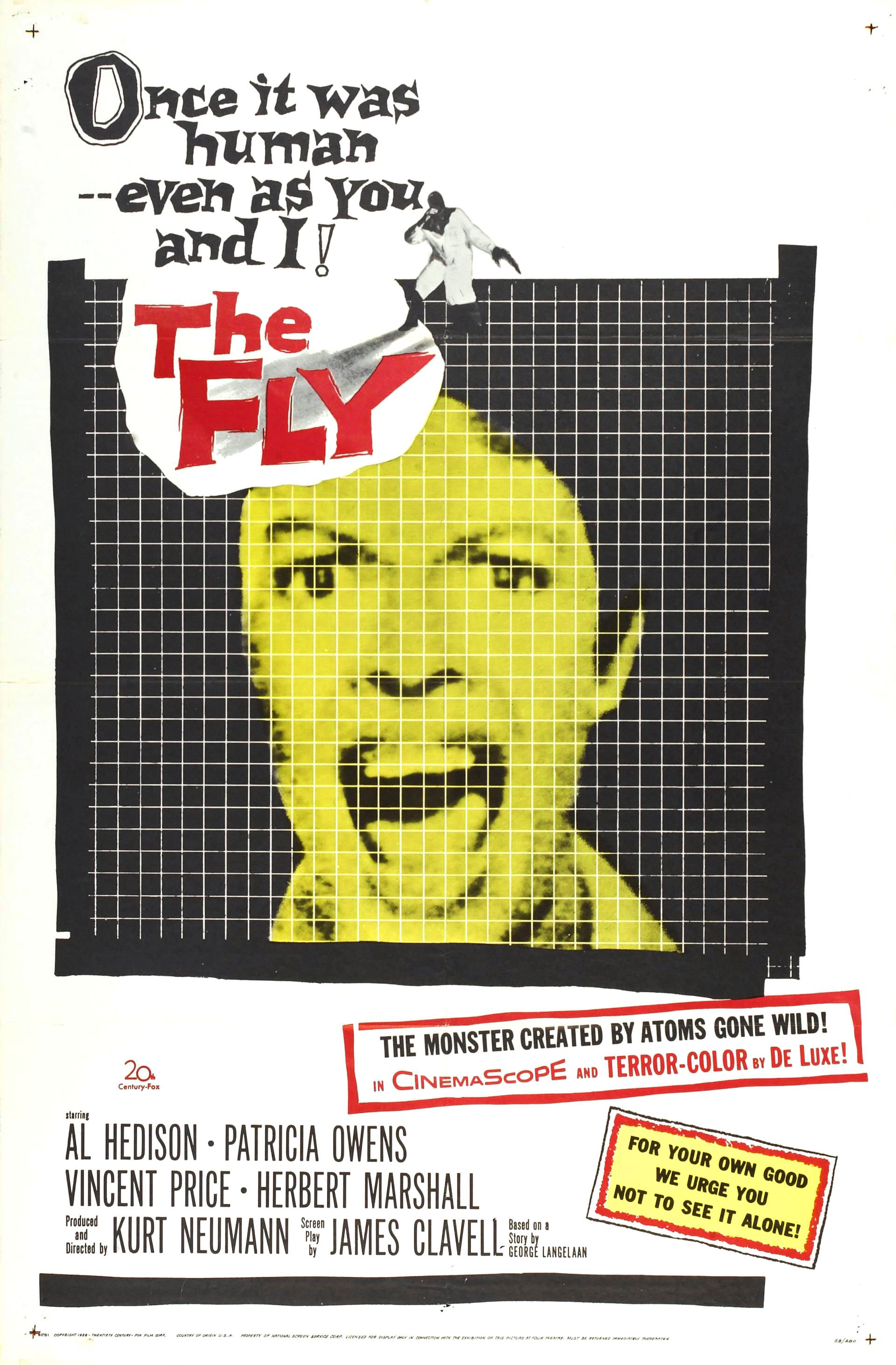

Most of the films featured in the October Horrorshow: It Came from the ’50s reviews haven’t been all that good. Some have been downright cheap and awful. Such is the life of the shitty movie fan. But then there is something like today’s film, The Fly. I wouldn’t characterize it as a classic, other than in the sense that it’s old. Rather, it’s just a decent film from the time.

Released in the summer of 1958, The Fly was produced and directed by Kurt Neumann from a screenplay by James Clavell, who would go on to write some of the lengthiest novels known to man. There’s a plodding nature to this film that I think can be blamed partly on Clavell.

The Fly follows the trials and tribulations of the Delambre family, industrialists in Montreal. The film opens with a grisly discovery. One of the Delambre brothers, André (David Hedison), has been murdered. His head was placed in a hydraulic press and crushed beyond all recognition. That’s a rather poor way to go, made worse by the fact André’s wife, Hélène (Patricia Owens), has confessed to pushing the button. André’s brother, François (Vincent Price), has a hard time believing that his sweet sister-in-law could be a killer, but she insists that’s what happened, and begins to relate events to François and the audience in flashback.

André and François own their company equally. François handles the business side of things, while André spends his time in a basement laboratory cooking up ideas for new products. His latest idea is a whopper, one guaranteed to change the very nature of  human civilization. André has invented a teleporter, similar to what would later be featured on Star Trek. He can send living or dead matter from point A to point B at the speed of light, perfectly intact and unharmed. There were some misfires at the start, but for all appearances, the process works.

human civilization. André has invented a teleporter, similar to what would later be featured on Star Trek. He can send living or dead matter from point A to point B at the speed of light, perfectly intact and unharmed. There were some misfires at the start, but for all appearances, the process works.

However, André didn’t test what would occur if two different objects were sent at the same time. André, in a fit of hubris, decided to send himself through his teleporter. But, he wasn’t alone. A fly snuck into the booth with him, and the teleporter machine combined the two on the other end of its cycle. André is now deformed, with the head and appendage of a fly (credit to Ben Nye for creating the excellent and twitchy fly mask that Hedison wore).

The remainder of the film follows André and Hélène’s efforts to reverse the process that harmed André. Because of his fly’s head, André can only communicate in writing. Very slowly, in writing.

Remember that plodding nature to the film I wrote about, above? It’s in this sequence that a viewer will feel it the most. The setup before the accident took up over a half hour, which was pushing it. This second act hardly ever leaves two or three sets, however, with most of the scenes taking place in the basement laboratory. The film feels much like a modest stage production by this point. Sometimes there’s a maddening lack of forward motion in the dialogue, as if Neumann was trying to pad the running time. But he didn’t need to. At 94 minutes, this film is actually a little long. There is plenty of excess footage that could have been done away with to address the lack of pace.

Of final note is a scene near the end where we see what happened to André’s human head and arm, and it’s a howler. Back in 1958 this little sequence might have been terrifying. In 2019, it made for a much-needed moment of levity.

The Fly is regarded fondly as a part of film history. Perhaps that has more to do with the big reveal of André’s deformity than it does with the actual quality of the film. The film was a success, and it deserved to be, but it is flawed. The pace makes viewing somewhat of a slog, and, not being a work of high art, that hurts the film. For a viewer interested in the history of film sci-fi and horror, though, it’s worth seeking out.