Cameron Crowe has made a number of films of note. His films consist of entertaining, escapist, happy storytelling that has about as many sharp edges as a bowl of jello. He made the type of films that challenge no assumptions, and throw in just enough emotion to tug on the heartstrings. The worst part about this is not all the squishiness, but the fact the only reasons his films arouse any emotional responses at all is because they are manipulative, reducing human emotion to a formula. Crowe doesn’t evoke emotions in a viewer — he extracts them.

Cameron Crowe has made a number of films of note. His films consist of entertaining, escapist, happy storytelling that has about as many sharp edges as a bowl of jello. He made the type of films that challenge no assumptions, and throw in just enough emotion to tug on the heartstrings. The worst part about this is not all the squishiness, but the fact the only reasons his films arouse any emotional responses at all is because they are manipulative, reducing human emotion to a formula. Crowe doesn’t evoke emotions in a viewer — he extracts them.

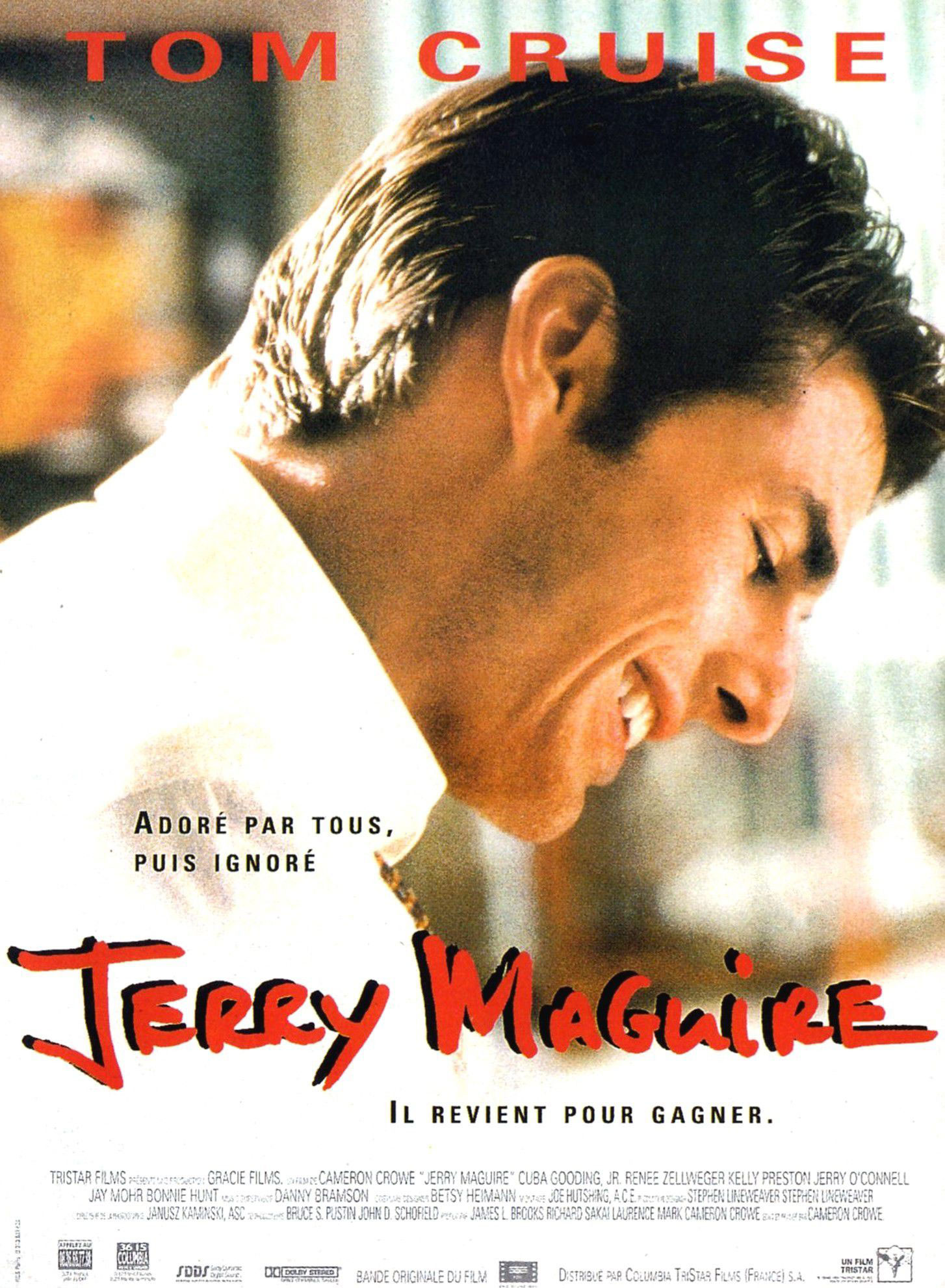

At the start, Jerry Maguire, Crowe’s film from 1996, freewheels its way through the life of the titular character, played by Tom Cruise. He’s a sports agent, and his life is shown as one of glitz and glamour, right until the moment he finds himself the public spokesperson for clients in trouble with the law or in trouble with the media. (Is there really any difference when it comes to sports?)

Jerry Maguire is on the cusp of being a wonderful film about the compromises, lies, manipulations, and confrontations of being a sports agent. There is a hard-hitting film waiting to be made about people like Jerry, but this isn’t it. Rather, this film is a romance whose main character happens to be a sports agent. It doesn’t matter what career Crowe could have chosen for Jerry. Lawyer, doctor, politician, etc. These and more all have potential for its practitioners to suffer crises of conscience, which is what happens to Jerry.

Jerry’s crisis leads him to become romantically involved with Dorothy Boyd, played by Renée Zellweger, a single mother who has placed far too much confidence and love into the struggling Jerry. The film flows back and forth between Jerry’s struggles with his fledgling agency and his faltering romance with Dorothy. It’s here that Crowe shows he has a large amount of deftness as a storyteller. Jerry is not the type of person whose life is divided in two — work and personal. Jerry’s crisis and his career collapse have made it impossible to set up the type of dividing lines in his life that so many of us do. And that’s not a good thing for Jerry. There being no separation, there is no opportunity for him to step back from the edge. Again, there’s a hell of a movie somewhere in here.

Jerry’s only client is bombastic NFL wide receiver Rod Tidwell, played by Cuba Gooding Jr., who won an Oscar for the role. Despite having myriad reasons to find representation elsewhere, Tidwell sticks with Jerry. This being a squishy film, it’s fairly obvious that by the end, Jerry gets Tidwell a good contract, and also patches things up with Dorothy. But, before that happens, viewers are forced to endure some of the most excruciatingly soft scenes ever put to film. It’s like being beaten to death with a feather pillow.

Then there are what I have come to think of as The Four Horseman of the Cinepocalypse — four iconic lines that crept into and poisoned pop culture for years after this film was released.

“Show me the money!”

“Help me help you.”

“You complete me.”

“You had me at hello.”

Whenever I hear these lines I close my eyes and picture the earth being scorched by flames. I see cities and fields crushed beneath the hooves of the four demonic horses. One is ridden by a pale rider with black holes for eyes, just visible through a slit in a soot-black helmet. The rider stops as he notices people fleeing at the feet of his steed. He lifts the visor of his helmet and the face of Jonathan Lipnicki stares out. He breaks out into cackling laughter as he swings his sword to riven the earth.

I will leave you, dear reader, with this single word sentence, written at the bottom of the notes I took for this review:

BARF.