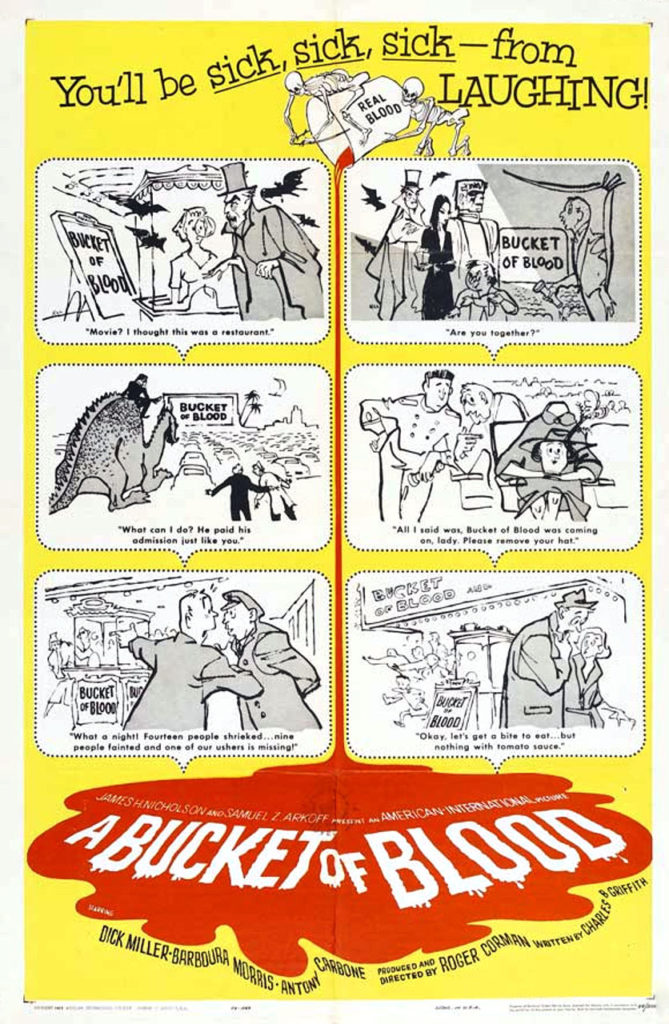

This year’s Horrorshow is nearing the end, and I could not let the month pass by without adding a Roger Corman flick to this list. It’s one of his best.

A Bucket of Blood, released in 1959, had a budget of $50,000, and a five-day shooting schedule. That type of swiftness and frugality was perfect for Corman, who never met a budget that was low enough to his liking. The first of Corman’s comedic collaborations with writer Charles B. Griffith, A Bucket of Blood is satire of the highest order. Its target are beatniks, a subculture which faded away decades ago. It features all the familiar targets of beatnik mockery. Berets, black turtlenecks, coffeeshops, poetry, folk guitar, heroin, pretentiousness. It’s that last part that made the beatniks such an easy target, and, in this film, a hilarious one. A typical line in the movie said by a swelled-headed beatnik was, “One of the greatest advances in modern poetry is the elimination of clarity.” That says it all about the artistes of this movie.

The late, great Dick Miller plays Walter Paisley, a busboy at a beatnik coffeeshop who wants nothing more than to be an artist and gain the respect of the cafe’s patrons. The self-appointed lord of the local set is Maxwell H. Brock (Julian Burton). He is the arbiter of artistic legitimacy, and bestows it on Walter after he produces a lifelike clay sculpture of a cat with a steak knife in its side. What Maxwell, and the other patrons of the cafe, don’t know, is that there is a real cat inside the sculpture, which Walter had accidentally killed.

Walter is flush with success. But, what will be his followup? Enter Lou Raby (Bert Convy), an undercover cop who follows Walter to his apartment to make a drug bust. Walter brains him with a pan, and he has his next sculpture. Walter is now a murderer.

Meanwhile, back at the cafe, the owner, Leonard de Santis (Antony Carbone), knocks Walter’s cat sculpture off a shelf and discovers the dead cat underneath. Leonard does little more than shake his head at what Walter has done, until he sees the next sculpture of a  man with a gaping head wound, and is horrified at the realization that Walter is a killer. He doesn’t go to the police, though. Rather, he begs Walter to change his style from realism to freeform sculpture. The customers of the cafe are aghast. Why should Leonard try to steer Walter away from what his genius is producing?

man with a gaping head wound, and is horrified at the realization that Walter is a killer. He doesn’t go to the police, though. Rather, he begs Walter to change his style from realism to freeform sculpture. The customers of the cafe are aghast. Why should Leonard try to steer Walter away from what his genius is producing?

Walter, for his part, kind of feels guilty about what he is doing. He never tries all that hard not to be a murderer, though, and finally just goes with it.

Of course, the only way this story could go is Walter’s murderous fraud being uncovered. There follows chase, denouement, fin.

One of the great things about this movie is that it doesn’t overstay its welcome. A Bucket of Blood clocks in at 66 minutes, and it didn’t need to go on any longer. What could Corman really have accomplished with another twenty minutes, or more, in the can? The story is spare, consisting of mainly two things: activity in the cafe, and life and murder in Walter’s studio. The cafe is the heart of the satire, while Walter’s meager living situation is where we learn the most about Walter as a character. The dialogue in the cafe scenes is the most precious, while the studio scenes are a comedic look into the life of a lovable loser. Even when he’s murdering people, Walter is still a sympathetic character.

Besides Griffith’s writing, the cast does much of the hard work that makes this movie work. Miller and Burton were both great, with Burton’s haughty affectation only off-putting if he happened to be a real person. Carbone was also good, his role being the closest this film gets to an audience surrogate. His is the only character that had an eye-rolling awareness of the beat subculture, and just who Walter really was. The other performances of note were Barboura Morris as Carla, Walter’s would-be love interest, and Myrtle Vail, as Walter’s bewildered landlady, Mrs. Swickert.

A Bucket of Blood may have targeted beatniks, but it’s still funny today because pretentiousness is still with us, and deserving of mockery everywhere it rears its ugly head. A film like this is a reminder that every generation has a tiny revolution at some point, where the mores of the squares are rejected in favor of light hedonism, at least until the immortality of one’s twenties is left behind.