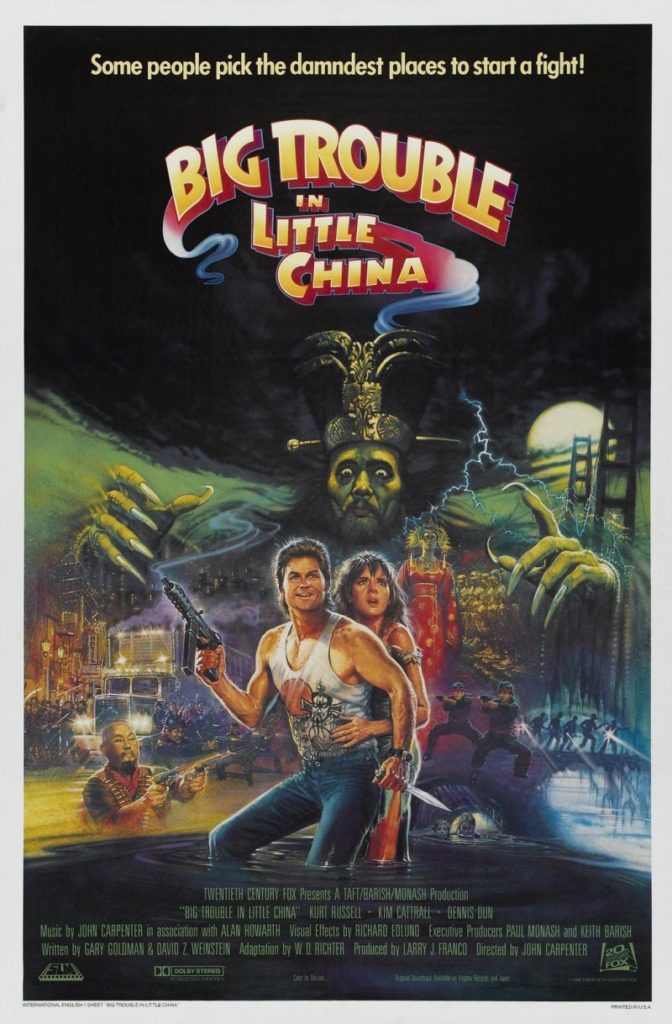

As I was watching John Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China recently, I was struck by the familiarity of the material. I felt I had seen it before, but in some other context. Confined, mazelike, and windowless environments; various tricks and traps the heroes must overcome; goons, monsters, and the bosses that control them, etc. And there it is. Big Trouble in Little China plays like a videogame. Considering it was released in 1986, before videogames became complex enough to compare, does that mean John Carpenter was breaking new ground, that Big Trouble in Little China is ahead of its time? No. It just reaffirms that the pacing and storytelling of today’s videogames are derivative of cinema. There are plenty of other films from around the same time that are akin to videogames (Aliens, Commando, and Total Recall all come immediately to mind, among many others).

In this day when videogames have taken an equal place alongside the other media that entertain us, and projects routinely cross from one to another, perhaps it is inevitable to watch a film like Big Trouble in Little China and think about how it would work with a controller in hand. Twenty years ago, Carpenter didn’t think about these things, nor could he have been aware that there would come a day when the comparison could be made. He was only aware of the kind of movie he wanted to make.

Big Trouble in Little China is an action film in the tongue-in-cheek subgenre. There is a large amount of violence, but it’s mostly cartoonish. It is almost devoid of blood and gore. The film is a story of heroes and villains, boiled down to base elements. There are no complications or moral dilemmas. There are no ambiguities. There aren’t even any betrayals. In an early fight scene, one of the characters helpfully explains that the guys in the gold sashes are good, and the guys in the red sashes are bad. That’s it. The battle lines are drawn that quickly and simply, and stick throughout the film.

One of the good guys is Jack Burton,  played by Kurt Russell. He’s a swaggering, truck-driving, beer-swilling, blue-collar philosophe who tries to channel John Wayne in both speech and mannerisms. He’s not afraid to take or throw a punch, and is exceedingly comfortable in the black and white world of the film. He shows remarkable patience for things he doesn’t understand, absorbing initial shock and disbelief at the mystical Chinese world he is thrust into, until the simple-minded focus of the character requires that the bitching stop as soon as action is required.

played by Kurt Russell. He’s a swaggering, truck-driving, beer-swilling, blue-collar philosophe who tries to channel John Wayne in both speech and mannerisms. He’s not afraid to take or throw a punch, and is exceedingly comfortable in the black and white world of the film. He shows remarkable patience for things he doesn’t understand, absorbing initial shock and disbelief at the mystical Chinese world he is thrust into, until the simple-minded focus of the character requires that the bitching stop as soon as action is required.

In many ways, Jack Burton is peripheral to the movie, an Anglo plopped into a faux-exotic set piece to keep an American audience grounded in the story. Burton is the hero, but he, and the audience, would have no clue about what was happening with the plot if the other, Chinese, characters didn’t take the time to educate Burton. Russell’s naïve, blustering Jack Burton is a neat indictment of American exceptionalism, in its way. There’s little reason to get too deep about it. Yet, the story of an American getting involved in Asian affairs he doesn’t understand was poignant in 1986, even in bubblegum fashion.

The heroes and villains of the film live in a fictionalized, transplanted China, one where black magic and demons are real. In the words of Victor Wong’s mysterious Egg Shen, leader of the gold-sashed good guys, “China is here!” Indeed it is, sort of. Carpenter’s vision of Chinatown is exotic and otherwordly. It’s a place westerners don’t understand, nor do they belong. As Jack Burton is a caricature of the self-absorbed American, Carpenter’s Chinese are all instant kung fu experts who run restaurants, fish markets, and import/export businesses. But it’s all in fun.

The villains are led by Lo Pan, played by James Hong, a veteran character actor who appears to be having loads of fun with the screen time Carpenter afforded him. He never appears in anything less than what looks like fifty pounds of costume and eight hours worth of makeup, but he breezes through the role. Other characters include Wang (Dennis Dun), whose actions ignite the plot, and Gracie Law (Kim Cattrall), who weighs it down.

Big Trouble in Little China is a good action flick. Every year that goes by leaves it that much more dated (there’s a bizarre amount of neon in the underground evil lair), but as 80s action movies go, it succeeds. It’s goofy and light-hearted, never takes itself too seriously, and doesn’t spend any substantial amount of time mired in a plot that could have gotten out of hand. As with many other Carpenter films, it’s advisable not to expect much, or to spend too much time trying to make sense of a plot even the characters ignore at times. The film is typical John Carpenter. There’s nothing award winning about it, but it has its qualities.