The year 1984 was an unforgettable year in geopolitics, and not for the reasons George Orwell thought. Overseas, the Soviet Union was dealing with a wheat harvest from the previous year that matched lows not seen since the 1920s. Even the scorched earth of western Russia during the Nazi invasion saw more plenty. Things were worse in Poland, a situation the Soviets took advantage of after food riots began and the Soviets occupied the country as peacekeepers.

In West Germany, elections saw the establishment of a radical isolationist government that demanded the removal of nuclear weapons from all European countries. The pressure they put on Washington with their demands, while not replicating said pressure on Moscow, effectively neutered NATO in all areas east of France.

South of the United States, Cuba’s and Nicaragua’s crash efforts to expand their militaries reached fruition, straining relations with Washington and further destabilizing a Mexico that was teetering on the brink. Not too long after, that country did indeed fall into rebellion, destroying law and order on our southern border.

Meanwhile, back in the states, what should have been an easy election year for Ronald Reagan saw his and the nation’s attentions absorbed by the spreading crises around the world. Not even a month after the GOP convention in August, NATO went belly  up and all the pressures of the world seemed to bear on the U.S.

up and all the pressures of the world seemed to bear on the U.S.

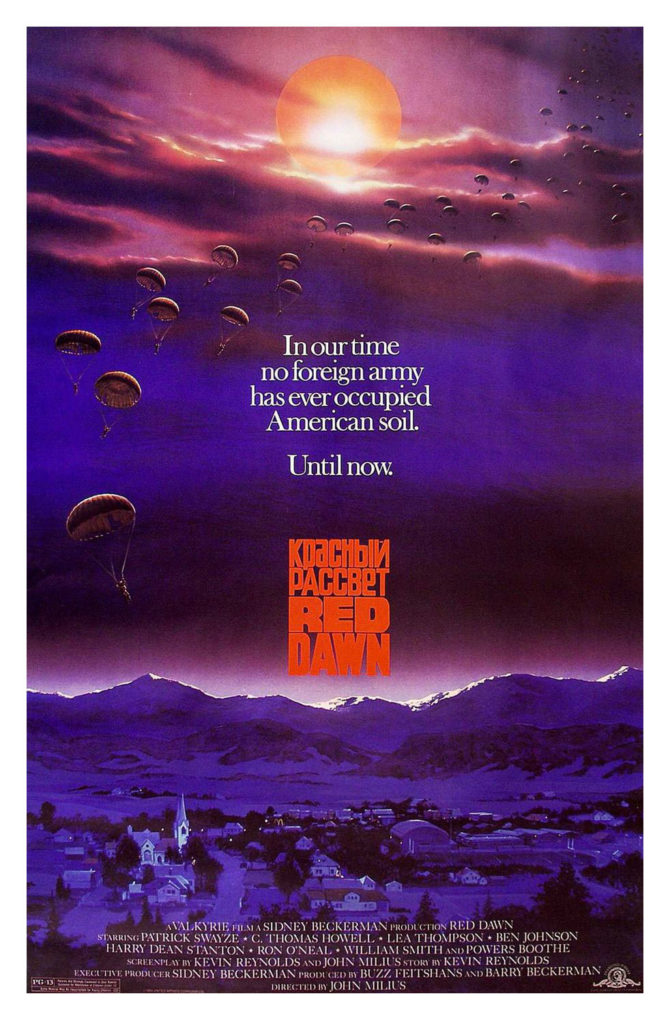

While what happened after should not have been a surprise, it was. American soil had not seen significant hostile military action since the Civil War, and not from foreign aggressors since the War of 1812. So when massive waves of Soviet paratroopers dropped into the middle of the country, acting as pathfinders for the Cuban and Nicaraguan armies which followed through Mexico, shock was the only reaction which seemed reasonable. Horror set in when it became clear that limited nuclear strikes had decimated Washington D.C. and other strategically located cities. Resolution set in when it became clear that though we had been bloodied, the foe we were facing could be hurt, too, and the long slog of war really set in.

Such was the framework director John Milius worked from when he and Kevin Reynolds wrote the film that became Red Dawn. Nominally the story of World War III, the wider tale of the penultimate war between east and west, that great conflict which captured a nation’s fears and imaginations for fifty years, served as backdrop to the story of a small group of young adults as they dealt with the invasion of their homeland. Mostly high school kids, led by an older peer, Jed (Patrick Swayze), they flee the city of Calumet, Colorado as the Soviet paratroopers land, hightailing it into the Rockies. There they intend to hide and wait out the war, but the atrocities the Soviet, and also Cuban, troops visit upon the friends and families they have left behind turn them into resistance fighters. The film follows the transition they make from green rookies to ruthless and efficient combatants who serve the greater good of the war by tying down enemy forces in rearguard actions.

Jed and his band, notably his brother Matt (a quite believable Charlie Sheen), Robert (a quite unbelievable C. Thomas Howell, but a favorite nonetheless), among many other classic characters, set out on a crusade to free the Rockies from the Reds.

Indeed, the commies have no clue how to deal with this small band of resistors, who have dubbed themselves the Wolverines after the local high school’s mascot. It doesn’t matter if they’re taking down a scout party or an armored column, the Wolverines kill every commie they see, and take nary a wound in the process as they build their reputation. Only the need for dénouement led Milius to place his protagonists in any real danger, but by then his creations had attained the ability to inflict supernatural levels of violence. Up until the point where the characters gain mortal attributes, Red Dawn is little more than predictable action fare with a substantial amount of propaganda thrown in for anyone who gives a damn.

What a turnaround for Milius. This is the man who wrote Apocalypse Now. Whether it was his intention or not, that film is decidedly anti-war. Nothing good happens in the entire film. Nothing. There is no message other than it is always wise to avoid war.

The Reagan years must have had an effect. Sometime between the late ’60s and early ’80s the Soviet bugaboo must have gotten to Milius. Not that it didn’t really exist. The conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States was very real, and resulted in far more deaths than the history books give true attribution to, but still. When you go from Colonel Kurtz to number 15 on National Review’s list of the best conservative movies, some monumental personal transformation must have taken place, right?

Maybe not. In dissecting the National Review rankings, another bugaboo appears: the old standby of liberal demonism.

First a disclaimer. National Review itself makes no claim that filmmakers represented in the list are conservative, or that even the films themselves are necessarily conservative, just that the films resonate with conservatives, because they “offer compelling messages about freedom, families, patriotism, traditions, and more.” This is familiar claptrap. Such generalizations apply to most, if not all, human beings, regardless of political beliefs. The continued co-opting of terms such as these by conservatives is one of the things that drives liberals and progressives crazy, mostly because there are a fair number on their side that buy it, as well.

The encapsulated review of Red Dawn offered by National Review, written by John Nolte, states in lofty mannerisms that “the truth that America is a place and an idea worth fighting and dying for will not be denied, not under a pile of left-wing critiques or even Red Dawn’s own melodramatic flaws...this story of what was at stake in the Cold War endures.”

Yes, the stakes were high. No stakes could be higher than that of Mutual Assured Destruction, and it is quite a lucky outcome that we came out of the Cold War without it going hot. That’s not hyperbole. Luck had so much to do with the lack of nuclear craters dotting the cities of the world that it is downright scary. But where I find issue is in the idea that only conservatives think the United States is worth fighting and dying for. I think that idea is insulting. For one, before the Gulf War, the previous four major wars the United States fought in were presided over by liberal Commanders-in-Chief. Woodrow Wilson: World War I. Franklin Roosevelt: World War II. Harry Truman: Korean War. Lyndon Johnson: Vietnam. That’s quite a track record of militarism, and all these men had wide popular support for their policies at the outset.

For Wilson and Roosevelt, the opposition from conservative isolationists as they led the country towards war made today’s rhetoric look tame by comparison.

Secondly, political ideology is the refuge of the comfortable. Despite what Chris Rock has said, if Russian tanks were rolling down Flatbush Avenue, ideology would have little place among the hate, anger and fear felt by the populace of the United States. What doubt could there be that an invasion of the magnitude depicted in Red Dawn would not lead to massive resistance among Americans of all political stripes? There’s never been a test of this theory, thank goodness, but the idea that conservatives would be solely responsible for keeping the flame is ridiculous. It’s one of the great illusions of American history that only conservatives are patriotic, and National Review is doing little more than stoking the flames of polarization. There are more meaningful arenas in which to wage such fights. That goes for Missile Test, as well. But they started it, I say.

With that in mind, upon taking a close look at Red Dawn, it is mostly neutral in the political ideology department. The main concern of the characters in the film is the invasion of their home by a hostile force, and their actions against said force. There is a price paid in blood on both sides. The message of the film is heroism. It is persistence in the face of adversity. It is resistance against oppression. It is the idea that freedom is worth fighting for, and it doesn’t call on any one ideology to acknowledge that. Red Dawn depicts a situation when the United States and the American people are actually given an opportunity to live up to the lofty rhetoric which both sides of the debate fling about with merciless abandon. Despite the film being a b-movie epic, it’s this underlying statement that gives it nuance and resonance.

Everything the characters of Red Dawn go through is absurd. The story is absurd, the invasion is absurd. But Red Dawn makes a person think. What would happen if we were to put our money where our mouths are, for real?

Is it worth watching, though? Well, Red Dawn came close to being a Shitty Movie Sundays review. The thing is, all of the complicated aspects of Red Dawn present themselves after watching it, and only if one were to look for or think about them. At heart, it’s a shoot-em-up. The first PG-13 film, for a time it was considered the most violent film ever made. That’s a flimsy claim, seeing as how it didn’t carry an R rating. In order to really appreciate Red Dawn, one cannot think about what they are watching. It’s that kind of movie. It’s that stupidly violent. Everything else was thrust upon Red Dawn after the fact because it involves communism and freedom fighters. I have to wonder sometimes if John Milius is sitting back, counting his checks, and laughing his ass off. Or whether he’s crying.

If the above is too opaque, I can write this unequivocally: a person’s film experience needs to include Red Dawn.