The tough-nosed cop with a disdain for the rules is a staple in film. Always butting heads with desk-bound lieutenants and mayors more concerned with getting reelected than cleaning up the streets, this breed of law enforcement officer has little time for procedure or the niceties of due process. Largely a fabrication of Hollywood, this cop operates in a world where the worse the crime, the more likely the guilty will go free due to the dreaded plot device known as “technicalities.” It’s all the more galling because there is never any doubt to the audience or to the hero that the bad guy is bad. Letting the bad guy go free because his rights were violated is nothing less than a miscarriage of justice, and it’s always left up to the hero cop to right such grievous wrongs. No film comes to mind that explored these ideas more effectively than 1971’s Dirty Harry.

The tough-nosed cop with a disdain for the rules is a staple in film. Always butting heads with desk-bound lieutenants and mayors more concerned with getting reelected than cleaning up the streets, this breed of law enforcement officer has little time for procedure or the niceties of due process. Largely a fabrication of Hollywood, this cop operates in a world where the worse the crime, the more likely the guilty will go free due to the dreaded plot device known as “technicalities.” It’s all the more galling because there is never any doubt to the audience or to the hero that the bad guy is bad. Letting the bad guy go free because his rights were violated is nothing less than a miscarriage of justice, and it’s always left up to the hero cop to right such grievous wrongs. No film comes to mind that explored these ideas more effectively than 1971’s Dirty Harry.

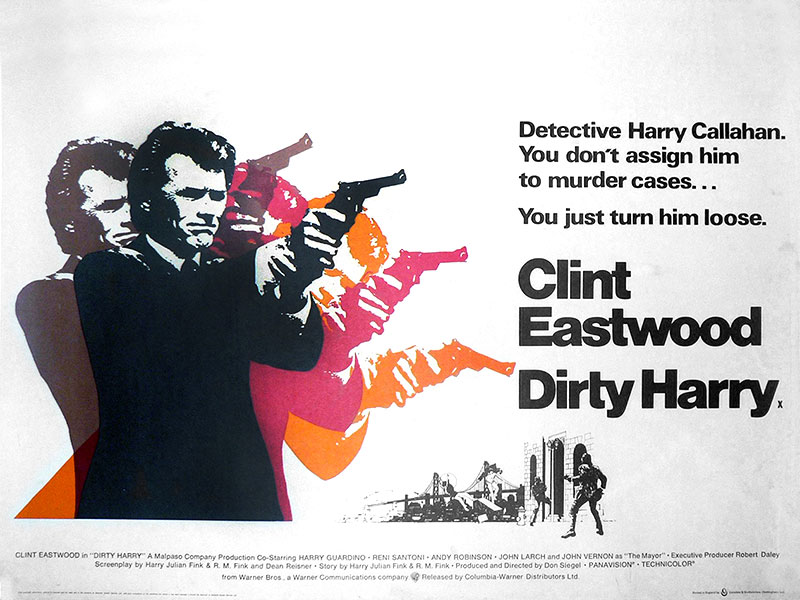

Directed by Don Siegel, Dirty Harry is the story of Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood), an inspector in the San Francisco Police Department. He’s gruff and unorthodox, but in a very polished way. To him the city is a sewer that should be walled off and left to consume itself. He has little faith in the inherent goodness of man, his job as a homicide detective taking him to very dark places on a seemingly daily basis. He’s a man full of hate, but with a pointed amount of compassion for victims. He’s also a fan of large caliber handguns, as evidenced by the cannon he carries in his shoulder holster, a weapon that has become as iconic in film as the character of Harry Callahan himself.

At that point in his career, Eastwood had spent the bulk of his time acting in westerns. A lot of cowboy swagger makes its way to 1971 San Francisco in Eastwood’s portrayal of Callahan. It would be easy to dismiss the performance as a masterpiece of stone-faced one-dimensionality, but that wouldn’t be fair. It’s worth taking the time to appreciate the nuance in the performance. Westerns are full of tough guys, and Callahan is no wimp, but he also carries around a lot of horror at the state of American society on his shoulders. Callahan seems to feel it’s all breaking down, and far from being resigned to the fact, he’s fighting it. All it takes is one look from Eastwood at a crime scene or when dealing with a suspect, and this sense of burden is conveyed to the viewer. Add in a feeling that Eastwood could make Callahan come unhinged at any second, and it becomes clear Eastwood nailed the role.

The film opens with a sniper shooting a swimmer in a rooftop pool. He calls himself Scorpio (Andrew Robinson), and he’s holding the city hostage for a pile of cash or he will kill again. In fact, Scorpio is a psychopath, and it’s clear that even getting his money would not stop the killing; he’s having too much fun. Robinson is gleefully scary as the killer. It’s such a signature role, and such a departure for the recognizable character actor, that I did a double take while doing my research for this review. I had no idea it was Robinson that I had just watched playing Scorpio. He inhabits the role so completely that he seemed to leave his face behind on the set when filming wrapped. Eastwood and Robinson, Dirty Harry and Scorpio, operate on an even plain in this film, the highlights being when they share screen time.

Most of the film is Callahan following the trail of Scorpio and trying to keep him from killing again. There’s no mystery for the audience as to who the killer is. It’s not a whodunit. It’s a manhunt. Twists and turns lead to a number of tense and brutal scenes, and it’s in these that the film shows its true hardboiled nature.

Dirty Harry is not popcorn entertainment. There’s little letup from the meanness that permeates throughout. What makes this impressive is it’s hard to picture the film not being dumbed down if it were made today. In the other direction, noir thrillers from the decades before Dirty Harry tread lightly compared to this film. It exists in a sweet spot of festering realism, yet before cultural mores changed what is acceptable for mass audiences to see on screen. To wit, other than the 1970s, in what other era of film could there be a full frontal nude shot of the corpse of a teenage girl being hauled out of a culvert? Far from the highlight of the film, this image does drive home its raw nature.

Of course, much of the realism of the film finds itself undercut by its fantasy. As hinted at above, Dirty Harry is an exposition on megalomaniacal police as much as it is a crime story. It’s simple and ignorant to think that rights exist to protect criminals only. Rather, they exist to protect the innocent from cops like Harry Callahan, who don’t always operate with the benefit of such cut and dried madmen like Scorpio. Dirty Harry takes the easy way out when it comes to confronting the issue of crime. Remove Scorpio from the equation and replace him with a misidentified innocent, and the film becomes the tale of the worst cop known to man. Even a little civic knowledge can make this film raise a viewer’s hackles. But never mind all that. Dirty Harry is a classic of cinema. It’s tough, tense, well-acted and directed; a fantastic film from a time when the studio system showed a substantial amount of bravery.