Teleportation is a fascinating subject. Most sci-fi fans have watched the transporters in Star Trek or elsewhere and thought how cool it would be to travel instantly from one place to another. But then science rears its ugly head. Sure, it’s a novel idea, and would change the way we live in ways that are hard to comprehend. For instance, if distance becomes meaningless, so does security and privacy. There’s no point in having locked doors if anyone at anytime can just teleport into your apartment and steal your stuff. There’s no point in living in cities if you can have cheap housing in the boonies and just teleport into midtown for work. Hungry for some Italian food? Forget the quaint little place that just opened in the old downtown, in the spot the shoe store used to be. Go to fucking Italy! Teleportation would be such a revolution in the way we think about distance that it would remake society in ways we can scarcely imagine. But there’s a dark side.

Teleportation is a fascinating subject. Most sci-fi fans have watched the transporters in Star Trek or elsewhere and thought how cool it would be to travel instantly from one place to another. But then science rears its ugly head. Sure, it’s a novel idea, and would change the way we live in ways that are hard to comprehend. For instance, if distance becomes meaningless, so does security and privacy. There’s no point in having locked doors if anyone at anytime can just teleport into your apartment and steal your stuff. There’s no point in living in cities if you can have cheap housing in the boonies and just teleport into midtown for work. Hungry for some Italian food? Forget the quaint little place that just opened in the old downtown, in the spot the shoe store used to be. Go to fucking Italy! Teleportation would be such a revolution in the way we think about distance that it would remake society in ways we can scarcely imagine. But there’s a dark side.

Much of the literature, and even a fair bit of science, regarding teleportation revolves around the breakdown of an object or a person into base particles. Those particles are either transmitted over distance, or the sequence is recorded as a digital file which is then reassembled elsewhere. (Quick aside: storing an object as a digital file means it is reproducible. All one would need is the raw material and the right file, and literally anything could be reproduced by a teleporter. Strawberries, the best bottles of wine, televisions, etc. A successful teleporter would be the culmination of the post-scarcity economy, which also coincides with the end of human ambition.) Part of both of these events requires that the material at the source is disassembled. That is, an object, or a person, is ripped apart into billions and billions of tiny bits as part of the teleportation process. Many people have noticed that the process does not sound like it is survivable.

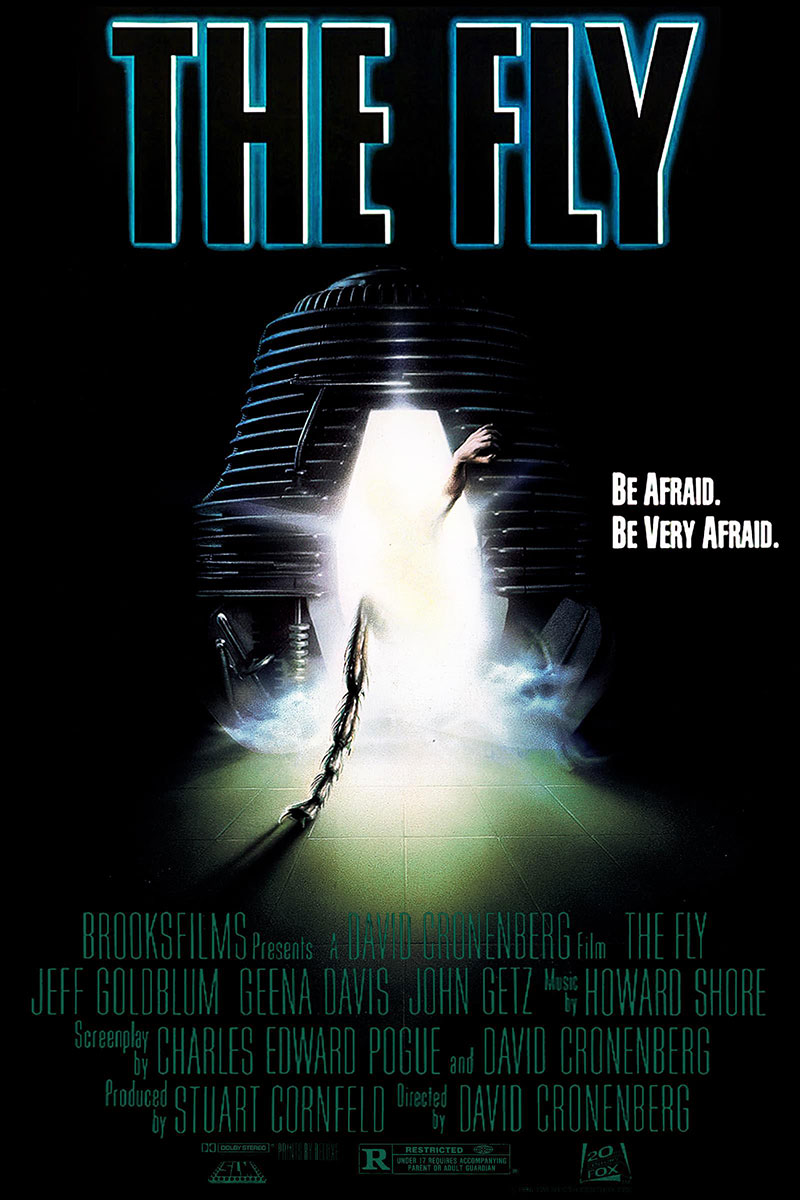

Then come all the wild ideas. Such as, if a person teleports, and the base material is destroyed at the source, then the person that materializes at the other end is not the original, but a copy. The original has died a gruesome death, pulled apart in a violent spasm on an atomic level. It’s not a pretty thought. Then there’s the idea that, yes, a person could be teleported, but they would arrive at the other end dead, because breaking down a living thing into base elements and reassembling does not confer life. After all, a corpse is made up of the same material as when they were alive. One would have to build a machine that can understand what it means to be alive, and transmit that information along with the raw material. What a mountain to scale. Either way, teleportation, for now, anyway, is the province of science fiction. It is also the main premise behind what I am declaring to be the marquee film of this year’s October Horrorshow, David Cronenberg’s The Fly.

From way back in 1986, The Fly stars Jeff Goldblum as a socially awkward scientific genius, Seth Brundle, who has uncovered the secret of teleportation. He keeps it in his living room. It consists of two Giger-esque booths and a computer that is advanced beyond all realism, but so what. It’s a movie.

Seth can teleport all the inanimate matter he wants. But he’s having problems with living things, carrying out unfortunate experiments on baboons, when surely mice, or anything else smaller than a baboon, would have been sufficient. Never mind, though. Seth Brundle has invented a working teleporter! He’s the greatest genius in the history of science, yet he, and journalist/love interest Veronica (Geena Davis) can’t seem to grasp that it doesn’t matter whether or not he can re-materialize a steak that doesn’t taste like plastic. It’s the biggest plot hole in the film. Here we have the means to send any inanimate object anywhere, and it’s regarded as a failure because it turns living things into raspberry jelly. Get past that, though, and there’s a hell of a film to be had.

Veronica spends her time torn between her love and devotion to Seth, and fending off the creepy advances of her ex-boyfriend Stathis (John Getz). Stathis is a weird character. For half the film, he hovers just above being a rapist. There are no redeeming qualities to his character whatsoever. Then all of a sudden, about halfway through, he becomes Prince Valiant. I cannot think of another character in a film that did that much of an inexplicable 180 with so little warning. It makes me think the character would have been better served being a stalwart fellow from the start, but what do I know about filmmaking and character development?

Anyway, Seth, in a jealous drunken stupor, decides that the time is right to give his teleporter a personal try, and he sends himself through the machine. All seems to go well, except a fly found its way into the booth right before he took his trip, and the computer, not knowing any better, combined Seth and the fly. What follows is a gruesome series of scenes where Seth is overcome by the wayward genetics of the fly, and transforms into a monster.

Cronenberg is a master at fostering uneasiness in an audience, and his technique is on full display here. There’s nary a manic moment throughout until the climax, but there’s always a feeling that things could go violently wrong. The brutal nature of some of the scenes as Seth loses his mind never come off as expected, and the disturbing imagery, coming one after another, is just downright disgusting. The Fly is an opus of disquietude. And through it all Goldblum is a rock. It’s a signature performance. Sure, it has a lot in common with everything he’s done since, but the man is no Olivier. It’s this role that set the bar for everything he’s done since. Even when he’s slathered in pounds of makeup, the character of Seth comes through.

The Fly is a tough film. It requires a strong stomach to watch, but the viewer will be rewarded with a fantastic exploration of a person in physical and emotional breakdown. And, it’s actually a bonus that this idea is wrapped in a gory horror film.