I like Psycho II better than Psycho.

— Quentin Tarantino

Slow your roll, Quentin.

I’m taking that quote out of context. It is possible to like one film more versus another, while recognizing that film A is not as good as film B. For example, I have a short list in my head of my favorite movies. Star Trek II is on that list. I can watch that film at anytime. I love it because it’s a wonderful sci-fi flick, with lots of action and a comprehensible story. I also love it because if there had never been any other Star Trek film made, if there had never been any of the television series, it could stand on its own with none of the decades-long backstory. But I will never, ever, say that it is a better film than, say, A Prophet, or Jiro Dreams of Sushi, to name two better films I saw this year. Those two films are better, but they will never come close to attaining the same level of appreciation I have for Star Trek II. It just cannot happen. So I understand how Quentin Tarantino, who has a much more thorough understanding of cinematic history than I, could like Psycho II more than Alfred Hitchcock’s original classic.

Sequels to cinematic masterpieces face an enormous challenge, not just in telling a good story, but in establishing legitimacy. Truly great films like Psycho become such a part of the fabric of cinema that any attempt to continue the story with a sequel risks offending the sensibilities of the audience more often than not. Only a handful of sequels have managed to pull it off, the common thread being the original cast and crew reuniting for subsequent productions. The Godfather and its sequel, The Pink Panther and A Shot in the Dark, Batman Begins and The Dark Knight, Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back.

Even more rare is the successful sequel that changed creative teams. Think Alien and Aliens. What Hollywood had normally fed audiences were films like Jaws 2, petty attempts to cash in on a recognizable brand. Before the current Hollywood era of reboots and  trilogies, this is what audiences could expect, so there was a tacit understanding that any sequel not only could not measure up to the original source material, but would be a subpar film to boot.

trilogies, this is what audiences could expect, so there was a tacit understanding that any sequel not only could not measure up to the original source material, but would be a subpar film to boot.

Any lover of Psycho therefore could be forgiven for dismissing the film without ever seeing it. But Tarantino, despite his bluster, has a point. Psycho II is not as good a film as Psycho. But, quite frankly, it is a damn good film, and a worthy sequel.

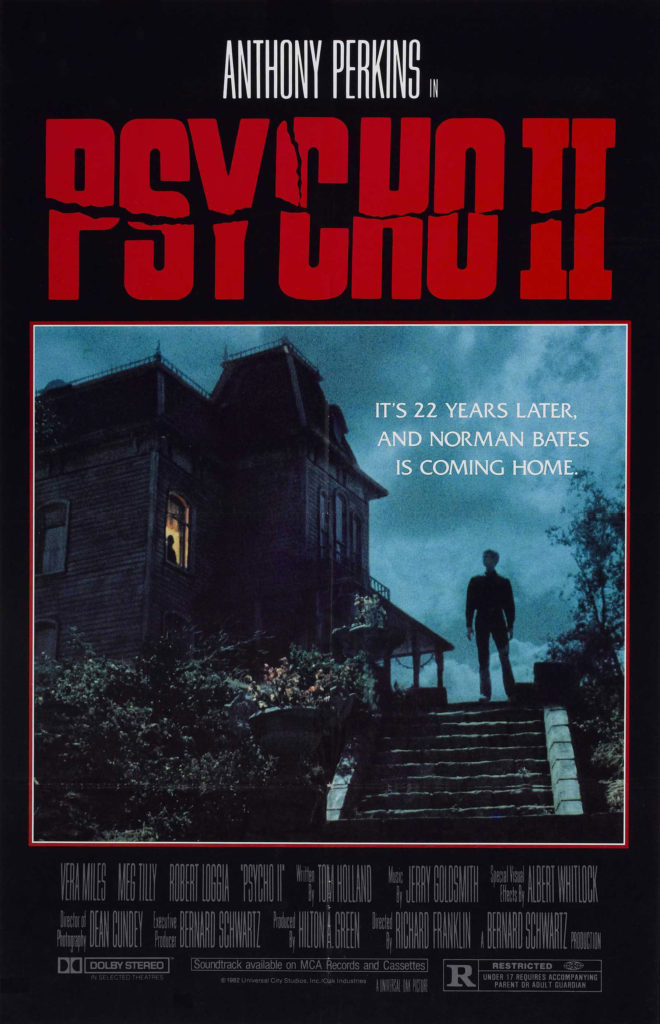

Taking place twenty-two years after the events of the first film, Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), after spending the intervening years committed to an insane asylum for his crimes, has been declared cured and released. He returns to his house and the Bates Motel, totally free to resume his life and live in peace. At least one person isn’t happy with the court’s decision, waving a petition in front of the judge to keep Bates locked up during his final hearing. But she can’t stop the wheels of justice from turning.

After being driven home by his psychiatrist, Dr. Raymond (Robert Loggia), Norman makes his way to a local diner that has agreed to take him on as a kitchen employee. There, he meets Mary (Meg Tilly). After a bit of cinematic acrobatics, Mary ends up moving into the Bates house. From there, the film gets going.

Norman may be cured, but he is hardly stable. Norman is conscientiously battling his demons, but he has to maintain constant vigilance over his mind to keep from falling back into the murderous abyss that landed him in the asylum in the first place. Mary is a reassuring presence he latched on to, but by this point a viewer is left wondering why she isn’t repelled by the sheer creepiness Norman oozes in every scene. There are ulterior motives I won’t go into here, but in short, there are people in the populace that do not want to see Norman Bates succeed. As the film rolls on, it becomes less clear whether events are the result of the conspiracy against Norman, or whether he has relapsed.

The lack of clarity regarding Norman is a great strength in the film. It keeps the audience guessing, and serves to keep Norman grounded as a character to root for. This is a character that murdered a whole pile of people in the original film, but the sequel successfully portrays him as a victim, as someone a viewer wants to see move into a stable and serene life. Any character that intrudes on this idea is seen as the enemy. What an accomplishment for the filmmakers.

As things continue, Norman begins to lose his grip, and it’s a wonderful process to watch. It doesn’t happen immediately, but is rather a slow burn from beginning to end, making it more satisfying and believable. Most of this has to do with Perkins. He was relegated to some serious b-movie roles during his career, but the fact remains, he was a very talented actor. In the original Psycho, he acted circles around everyone in the film, including Janet Leigh. This performance was not as stellar, but it was still very fine work, loaded with subtleties that reward multiple viewings. He plays Norman as one would expect a man who had spent almost his entire adulthood locked away from society and found himself suddenly turned loose. He is nervous, more than a little scared, and lacking in social skills that normal people take for granted. He is very childlike, but aware of his situation in a way that true innocence cannot be. It’s a joy to watch Perkins as Norman loses his grip on reality.

The machinations that surround Norman eventually reach their peak, setting up a very complicated and unexpected ending, but one that works quite well.

I was surprised at how good this film was. Much of this had to be due to the efforts of director Richard Franklin. He was a student of Hitchcock, sure to treat the material with respect. Combine this reverence with a strong script and a serious treatment from a cast that saw more than just a payday, and we have a winner for the October Horrowshow.