A general rule: films that are adaptations of books are not as good as the book. Why should they be? A film removes all the grace of prose, and by necessity compresses the story. Sometimes, though, films are better than their source material, and the rule is reversed. Jaws, Wolfen, Die Hard (aka Nothing Lasts Forever), Full Metal Jacket (aka The Short-Timers)...a list like this could go on and on. It’s strangely satisfying to watch a film that’s better than the book. But also confusing. All those films I cited above come from mediocre books. Yet the mind of a filmmaker was able to read them and think, “Yeah, this would make a good movie.” Okay.

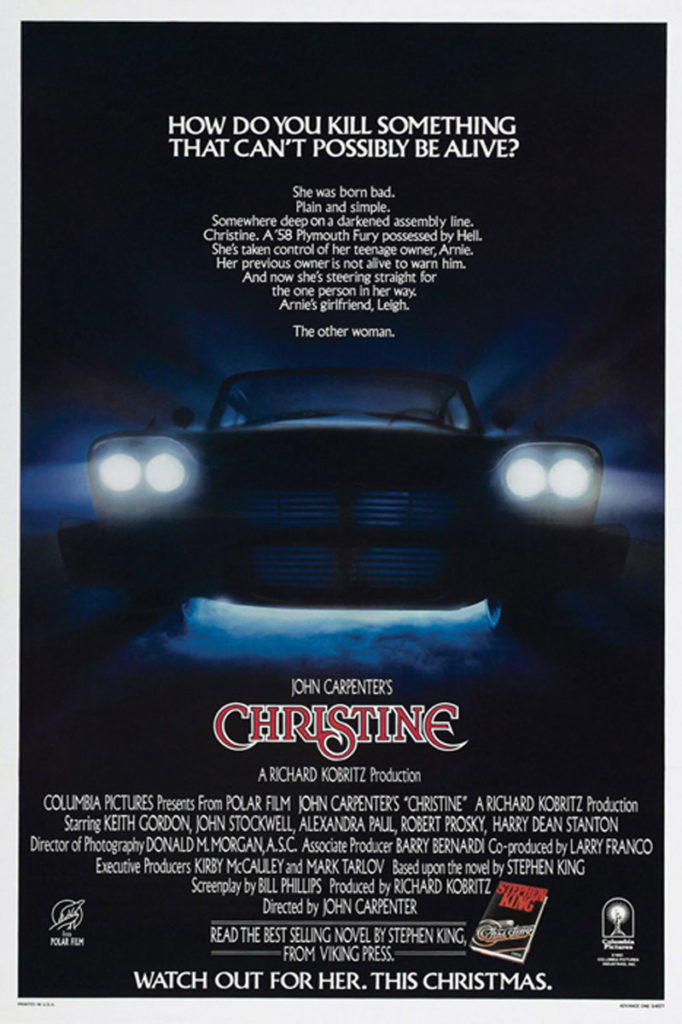

Another film that could be added to the list is John Carpenter’s Christine, adapted from a rather sloppy Stephen King novel of the same name. Christine, King being the hot commodity in Hollywood that he is, had yet to be published before Carpenter began filming. I’ve read that book. It should have stayed in King’s filing cabinet. But the film is a fine example of Carpenter in his prime. From 1983, Christine is sandwiched right into the middle of a five-year run that began with Escape from New York and The Thing, and ended with Starman and Big Trouble in Little China. That’s five years where Carpenter saw his infinitesimal budgets upped to merely miniscule, and his films were released widely. Like all his films, Christine is hardly a work of art, but is solidly crafted, with a well-executed story, and little evidence it was made on the cheap.

Christine tells the tale of teenaged  Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon), a bespectacled misfit who falls in love with a junker of a car he sees for sale in an old man’s yard, a 1958 Plymouth Fury the old man has named Christine. Arnie pours his heart, soul, and checkbook into restoring the car, but he becomes obsessed. It’s not completely his fault. Christine isn’t just some innocent, inanimate object. She’s sentient, and malevolent. She has a hold over Arnie, and is also very jealous and very possessive of him. For his part, Arnie’s mind is warped by Christine, until he becomes aggressive, paranoid, and dangerous. The film becomes a showcase of what happens when people, friends, family, enemies, what have you, come between Arnie and Christine.

Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon), a bespectacled misfit who falls in love with a junker of a car he sees for sale in an old man’s yard, a 1958 Plymouth Fury the old man has named Christine. Arnie pours his heart, soul, and checkbook into restoring the car, but he becomes obsessed. It’s not completely his fault. Christine isn’t just some innocent, inanimate object. She’s sentient, and malevolent. She has a hold over Arnie, and is also very jealous and very possessive of him. For his part, Arnie’s mind is warped by Christine, until he becomes aggressive, paranoid, and dangerous. The film becomes a showcase of what happens when people, friends, family, enemies, what have you, come between Arnie and Christine.

She’s a demonic piece of rolling iron, and there are some deaths.

Watching all this, and seemingly helpless to stop it, are Arnie’s best friend Dennis (John Stockwell), and his girlfriend Leigh (Alexandra Paul). They have to figure out a way to separate Arnie from Christine without being killed in the process.

The film consists mostly of set pieces bookended by violence of some sort. For a horror movie, it’s not scary, but it’s not that type of horror film. It wasn’t meant to shock, just to tell a horrifying story. A murderous car that runs people down in the street and that can regenerate damaged parts? That’s horrifying.

And the car itself serves that purpose well. A ’58 Fury might not be scary on its face, but replace it with a Honda Civic and it begins to make more sense. It’s a long-hooded beast with a big engine and huge fins. It weighs almost two tons. It’s a car from an era of body design that looked old less than a decade after it hit the road. It’s a ghost of the 1950s, and Carpenter made sure only the darkness came through, a surprising feat of filmmaking when you consider the nationwide nostalgia we have for the false innocence of the decade. Carpenter does such a fine job that he even manages to make Robert & Johnny’s We Belong Together sound like an evil theme song.

The film is a bit of a departure for Carpenter. His films have always been informed by an inherent mistrust of authority, even paranoia. But none of that comes through here. He hewed close enough to King’s novel that his own mischievous nature was set aside in service to the story. That makes Christine an interesting entry in Carpenter’s filmography. The film is still distinctly his, however. Anyone with even a passing familiarity with his films would be able to pick it out in a blind tasting. It just looks like a Carpenter film. More tellingly, it sounds like one, Carpenter having continued with his practice of scoring his own films. So while the troublemaker is gone, the filmmaker is still here. Check it out.