I’ve mostly steered clear of torture porn when it comes to watching horror flicks. Grievous physical injury has always been a part of the horror genre, but it’s only in the last couple of decades that depictions have crept closer and closer to reality. Every person out there has a threshold for how much violence they can stomach before a film is no longer enjoyable. Torture porn usually crosses mine. While most of the films in the Saw franchise not only cross that line for me, but go sprinting past it, the first film has far less violence than its reputation would lead one to believe. To be sure, having less violence than its successors leaves it room for still quite a bit, but when it comes to the Saw franchise, less is more.

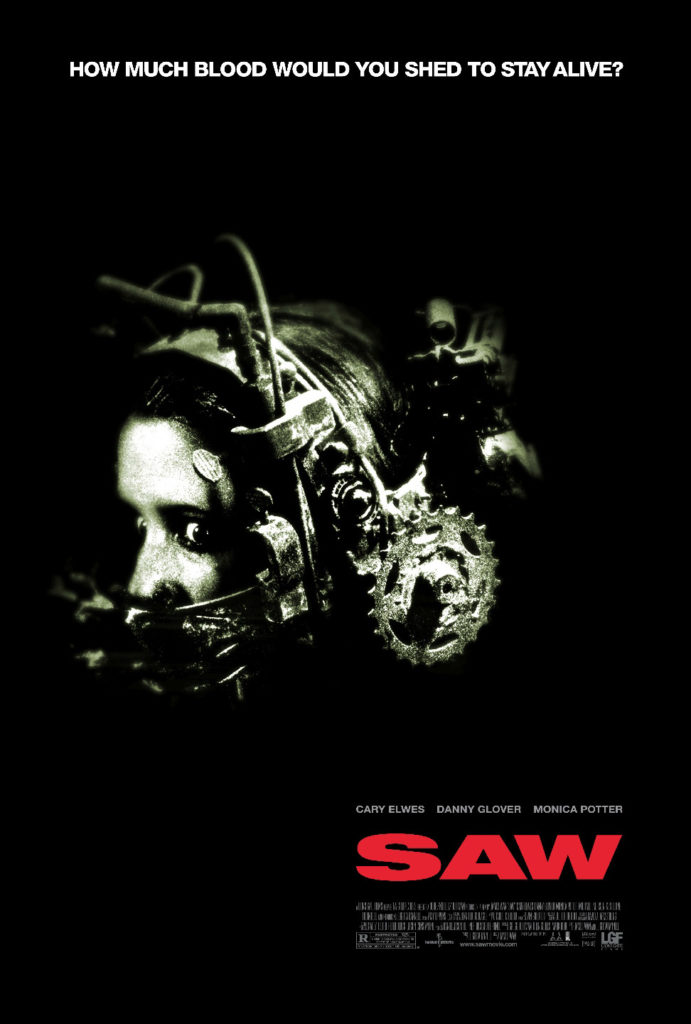

Written by Leigh Whannell and directed by James Wan, the debut feature for both, Saw tells a convoluted story used to justify atrocious acts of violence. Two men, Dr. Lawrence Gordon (Cary Elwes) and Adam Stanheight (Whannell), awaken in the world’s worst bathroom, chained to the plumbing on opposite sides of the room. They don’t know each other, and neither has any memory of how they got there. In the middle of the room, out of reach of the both of them, lays a corpse, a gun in one hand and a tape recorder in the other. It doesn’t take them long to figure out they are trapped in some sort of sick scavenger hunt, with the two pitted against each other. The prize for winning is life, while the loser dies. Such is the way of the games masterminded by the mysterious Jigsaw, the city’s newest serial killer.

Unlike other serial killers, Jigsaw doesn’t actually kill anyone. Rather, he creates elaborate puzzles and traps, testing his victims’ willingness to inflict horrible pain on themselves, or others, versus their desire to live. Play the game correctly, and a person survives. In Jigsaw’s twisted outlook, the survivors have been liberated.  They now understand what it means to truly be alive, having faced death and overcome it. Jigsaw has given them a gift. It’s nonsense, but that is what Jigsaw thinks.

They now understand what it means to truly be alive, having faced death and overcome it. Jigsaw has given them a gift. It’s nonsense, but that is what Jigsaw thinks.

Whannell and Wan appear to have come up with the idea of Jigsaw’s puzzle rooms, of which viewers see numerous examples throughout the film, before coming up with the thread that ties them all together. This is what I mean by torture porn. Saw consists almost entirely of these scattered locations where people are subjected to Jigsaw’s tortures, but these rooms are much more thought out than the plot. Time and effort was put into making Jigsaw’s puzzles gut-wrenching and sickening. But outside of the rooms, Jigsaw’s machinations, all the twists and turns leading to denouement, feel tacked on, contradictory, and purposefully confusing. If there was a way for the film to have been released without having to tell a story amidst all the gory showmanship, I am sure the two would much rather have done that. In that, Saw is like a Halloween funhouse. A viewer is taken from room to room where they are confronted by one gory spectacle after another, but little attention is paid to the other fine points of filmmaking.

It’s not like the two are incapable of doing that, as evidenced by later work in the horror genre. This was their first feature film, so perhaps there was still much room for their skills to grow. But this film exists solely to show its characters in pain. Everything else was conceived after the fact.

As to the quality of the filmmaking, at times it is no less gimmicky than Jigsaw’s traps. There are all sorts of quick cuts and hyper-fast camera movements, used as triggers to show the audience that something important just happened in the plot. The style is the filmmaking equivalent of auto-tuning, and it’s not holding up well a decade later.

James Wan has shown he is capable of directing a film with some depth since Saw was first made. But I think this movie had more to do with him getting the Fast and Furious gig than did Insidious or The Conjuring.

But does the spectacle of Saw overcome its lack of depth as a film? In many ways, it does. The reason Saw became a franchise is because there is an appetite for these types of films. Saw had a small budget, coming in at around 1.2 million dollars, and had box office of over a hundred million. That type of return is not a fluke. Whannell and Wan found an area of horror cinema that had not previously been satisfied by other films. Saw is a more base appeal to a viewer’s visceral sense of horror than most of what came before. Even with the strained and complicated story, Saw is a simplification of the horror genre. It assumes that what people want to see is the payoff, the journey being less important. The two filmmakers read their audiences correctly. Excoriating them for recognizing what audiences wanted to see is a little bit too high and mighty for this reviewer. Saw has all the narrative depth of a 1990s music video, and in many ways is stylistically the same. But in 2004, audiences were primed for just such a film. If Whannell and Wan had not made it, someone else would have.