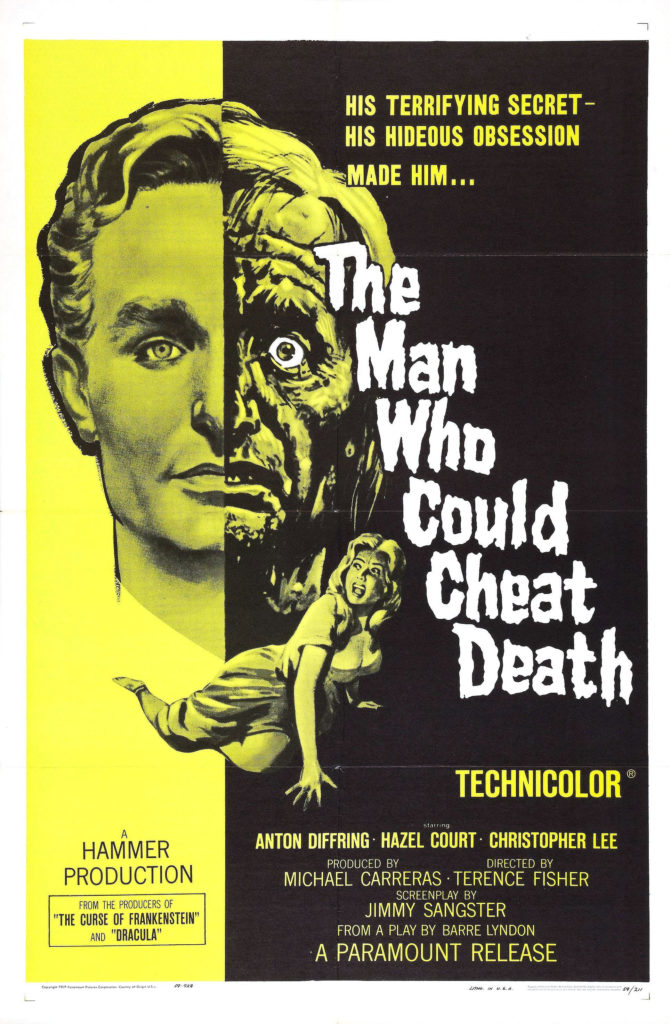

Terence Fisher directing, Jimmy Sangster writing, and Christopher Lee in a supporting role. The Man Who Could Cheat Death, one of Hammer’s efforts from 1959, should have been among the best films in this month of reviews. But it’s not, and that’s because while three of Hammer’s top names appear in the credits, a fourth, Peter Cushing, does not. He had been set to star in this film, but the lead role instead went to Anton Diffring, who was not equal to the task.

The setting is Paris, 1890. There, a successful physician to the aristocracy by the name of Georges Bonnet (Diffring), hosts posh salons where he debuts his latest sculptures. By all accounts, Bonnet is as talented an artist as he is a skilled physician. All the ladies love posing for him. But Bonnet has a secret. The youthful, energetic doctor has had plenty of practice — much more than people suspect. Georges Bonnet is, in actuality, over 100 years old, his youth sustained by a foggy serum and an operation he must undergo every ten years.

It’s time for a new operation, but the doctor who performs the operation, Bonnet’s oldest friend and confidante, Ludwig Weiss (Arnold Marlé), is now old and infirm following a stroke. A replacement must be found. Enter Christopher Lee as Dr. Pierre Gerard. He knows  Bonnet because his romantic interest, Janine Dubois (Hazel Court), knows Bonnet from earlier days. In fact, Janine and Bonnet had a torrid affair, which still lingers on in both their minds.

Bonnet because his romantic interest, Janine Dubois (Hazel Court), knows Bonnet from earlier days. In fact, Janine and Bonnet had a torrid affair, which still lingers on in both their minds.

Bonnet needs the operation badly. He has spent decades with his youth, all diseases and maladies held at bay by the procedure. But, those conditions haven’t been alleviated. Rather, they’ve been piling up like PCBs behind a dam, waiting for any breach to burst forth all at once. Every six hours Bonnet must ingest his mysterious serum or he begins to transform into a twisted monster.

A potential viewer might think they know where this story is headed at this point. It sets itself up like a Jekyll and Hyde story, where Bonnet prowls the night in his monstrous guise, eventually returning to normal and having to deal with the horrors his rabid, uncontrolled self committed. That’s not where this story goes. Bonnet is enough of a bad guy that there didn’t need to be a monster lurking within.

Sangster’s screenplay is an adaption of the play The Man in Half Moon Street, by Barré Lyndon. If the screenplay is any indication, the play was a talky one. For his part, Sangster looks to have made little effort to expand the screenplay beyond its stage play origins. Scenes are long, packed full of dialogue, much of it redundant, and locations are few. It doesn’t hurt the film, but there are missed opportunities.

The film, shot by Jack Asher, wasn’t photographed like a play, which helps tremendously. There aren’t a lot of wide shots or long takes, but these scenes have a somnambulistic pace that does hurt the film. A couple of these scenes are overlong and hard to sit through.

So, although this was a Fisher and Sangster film, this was not their best work. But the biggest problem with this film was its star. From his first appearance to his last in this film, Diffring could be counted on to overact. Sometimes he would overact a little, sometimes a lot, but if there was one constant, it was that he just could not turn off the intensity of his performance. His character was dealing with his prospective death, but that happens in countless movies, with countless other actors managing to convey some believability to the idea of impending mortality. There was nothing about Bonnet to root for, and, because the performance was so unpleasant, nothing about him as an antagonist to root against. I just wanted the film to be over so I wouldn’t have to watch Diffring any longer.

The Man Who Could Cheat Death is a missed opportunity. The story was just fine, but the execution was off by enough to keep it from being memorable or special.