True Grit, one of John Wayne’s most celebrated westerns, was released in 1969. The day it was released, it was already somewhat of an anachronism. The ’60s saw the western genre embrace more depth in its storytelling, something that was already common in many other genres. Before True Grit, there was the trilogy of films by Sergio Leone featuring Clint Eastwood as the man with no name. Just a week after True Grit was released, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch hit theaters. The western has rarely been a genre that strived for realism, but the violence of The Wild Bunch was a direct challenge to a film like True Grit, where violence and death are done by rote, removing much emotional punch.

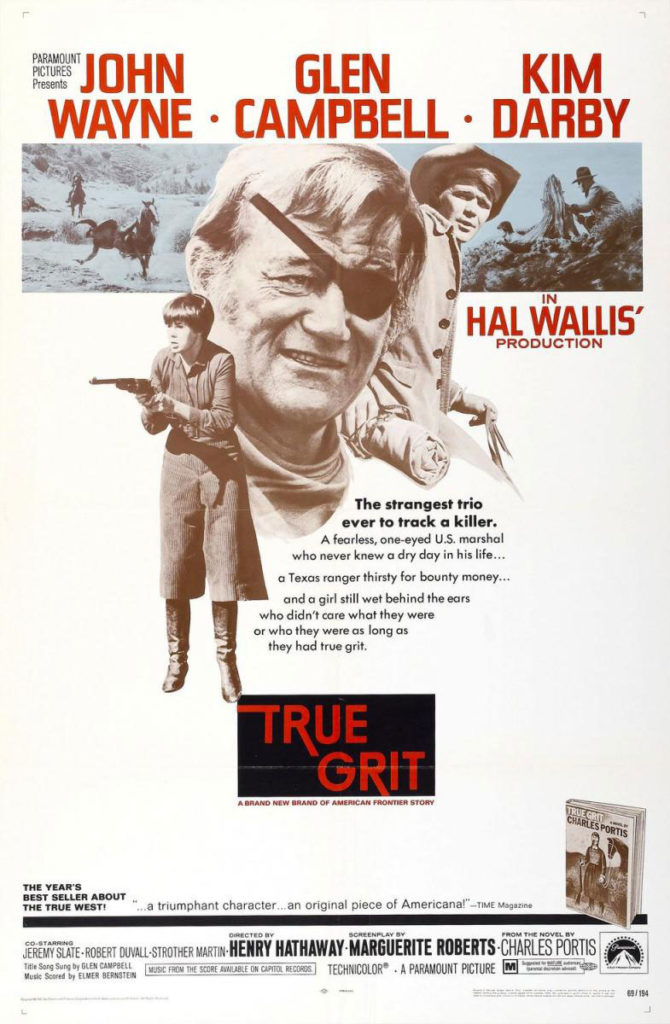

But, while True Grit adheres to a formula that had been successful for Wayne and Hollywood for decades, True Grit is considered a classic for a reason. Wayne won his Oscar for his role and Henry Hathaway directed, but it was Marguerite Roberts’s screenplay, adapting Charles Portis’s novel, that makes this film what it is.

True Grit tells the story of Rooster Cogburn (Wayne), a U.S. Marshal who chases down fugitives. He is hired by Mattie Ross (Kim Darby) to hunt down a farmhand who murdered her father. Soon after, they are joined by Glen Campbell as the Texan La Boeuf. So far, there’s not much to distinguish this film from hundreds of other westerns. But it was around this time, when the three protagonists began to gather around each other, that I began noticing the screenplay.

It’s a rollicking screenplay, with a feel fit for the stage as much as the silver screen. It’s full of western clichés and all the other service that the studio surely expected, but the characters of True Grit have real emotions and motivations. True Grit exists in a weird, transitional, space. American audiences were beginning to demand more out of their movies, but Hollywood was slow to change. For example, the standout scene for Wayne in this film is when Rooster tells a little bit of his history. It’s poignant, doing much to humanize a character that was as much Wayne as Rooster. The scene points to reasons and motivations behind Rooster’s drunkenness and violent behavior. Such background would have only been hinted at in an earlier era.

Then there is the presence of Glen Campbell as the film’s resident hunk. This was not the first western in which Wayne was saddled with a popular musician as a costar. Campbell’s presence only serves to remind the viewer that this film is a commercial enterprise, part of a buddy system between the recording industry and Hollywood that taints film to this day, but which was much more common in the past. Campbell had no business in such a prominent role, especially with Dennis  Hopper and Robert Duvall being underutilized elsewhere in the film. The filmmakers were less concerned with having a credible performance than they were in getting a hot corporate musician into the role (the role was reportedly offered to Elvis Presley before Campbell). At least Campbell doesn’t break out into song around a campfire (I’m looking at you, Rio Bravo). Seeing such a ham-handed casting decision feels out of place for a film from 1969.

Hopper and Robert Duvall being underutilized elsewhere in the film. The filmmakers were less concerned with having a credible performance than they were in getting a hot corporate musician into the role (the role was reportedly offered to Elvis Presley before Campbell). At least Campbell doesn’t break out into song around a campfire (I’m looking at you, Rio Bravo). Seeing such a ham-handed casting decision feels out of place for a film from 1969.

Another scene that points to True Grit existing between two eras of Hollywood was Dennis Hopper’s single scene. By 1969, Hopper was just about to alienate the powers that be in Hollywood, but he was still getting lots of work. The short scene in which his character, Moon, meets his end is the reason why. Hopper’s character is shot in the leg by Wayne, and later sat down at a table next to his partner in crime while Wayne questions them. While the other performers in the scene, Wayne, Campbell, Darby, and Jeremy Slate, all go through their lines with studied, old Hollywood proficiency, Hopper sits at the table and grimaces in pain, never forgetting that his guy has a bullet wound. Normally, a bullet wound in a Hollywood flick is treated as a mere inconvenience, but there is Hopper, during a stretch where he has few lines, never letting the audience forget that he has been shot. True Grit is a film that lacks in realism, in many places getting downright operatic, but Hopper wasn’t having any of that. He was a student of Lee Strasberg, and a decade and a half in Hollywood westerns had failed to scrub away the Method. In that scene, when everyone else was being typical and uninteresting, Hopper was acting like a man who had been badly injured, and, despite not being the focus of the scene, acting circles around everyone in it, future Oscar winner Wayne included.

True Grit is a beautiful film with a beautiful screenplay. It is a film from an era of Hollywood that was ending. Wayne and Hathaway could not be expected to abandon decades of experience, so, in fact, it does not matter that True Grit does not progress the art of film like many other films of the day. It doesn’t want, nor need, such a burden.