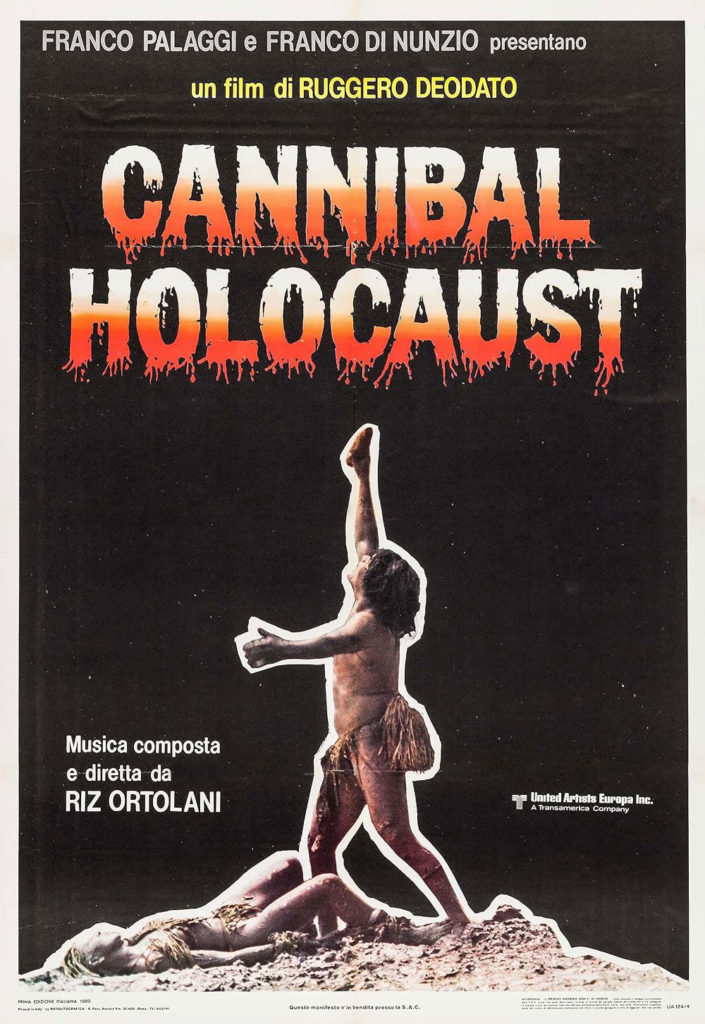

This one’s a tough watch, folks. Cannibal Holocaust, from director Ruggero Deodato, was not the first Italian cannibal horror flick, but it is the most notorious. It’s the most disgusting. It’s the most disturbing. It’s the most alarming. It’s the most guilt-ridden for the viewer. Its portrayal of death was realistic enough that Deodato was briefly charged with murder upon the film’s release in Italy. It has earned every bit of its reputation. It’s also one hell of a movie.

Cannibal Holocaust tells the story of four NYU film students who head to the Amazon jungle in Colombia to shoot a documentary about local tribes that practice ritual cannibalism. When they go missing, a professor of anthropology, Harold Monroe (Robert Kerman), heads to the jungle to see if he can find out what happened. He’s joined by guides Chaco (Salvatore Basile), and Miguel (possibly Ricardo Fuentes — the credits don’t say and the internet is divided).

The three of them trace the crew to a village of the Yacumo tribe, where they find the village has been partly destroyed. From there, they go deeper into the jungle, making contact with the Yanomamo tribe, and they discover that the four young filmmakers have been killed by the Yanomamo, and their cans of film turned into totems. By participating in some nudity and light cannibalism, Monroe is able to ingratiate himself with the tribe, and retrieve the exposed film.

Back in New York, the footage shot by the doomed film crew is screened for possible inclusion in a documentary, and viewers see just what happened down in the jungle. The second half of Cannibal Holocaust consists mostly of this footage, edited together into a coherent narrative. Viewers find out, much to their surprise, that the four young filmmakers, played by Carl Gabriel Yorke, Francesca Ciardi, Perry Pirkanen, and Luca Barbareschi, were not some innocents who blithely wandered into danger. The four were cruel, with no regard for the welfare of  the tribes they contacted. Indeed, the way they found the Yacumo tribe was to shoot one of their hunters in the leg, then follow him back to his village. That destruction Monroe found later? Turns out, that was the crew burning huts with villagers in them to fake footage of an attack by the Yanomamo.

the tribes they contacted. Indeed, the way they found the Yacumo tribe was to shoot one of their hunters in the leg, then follow him back to his village. That destruction Monroe found later? Turns out, that was the crew burning huts with villagers in them to fake footage of an attack by the Yanomamo.

The crew display the same kinds of behavior that made the Spanish Conquistadors so infamous. They burn, they slaughter animals, they rape, and they kill. It all ends when the crew set off to find the Yanomamo. The Yanomamo aren’t having any of their shit, and mutilate the four students in grisly fashion. In the end, they got what was coming to them.

That’s the plot of the film, but it’s not the plot that makes this such a difficult watch. It’s twofold. First are the depictions of violence. They are quite intense. It’s not enough for victims to be attacked with knives and axes. Scenes of violence include ritualistic rape with sharp objects, impalement, genital mutilation, etc. There are only a couple shots of gore here and there that weren’t convincing. Otherwise, the effects are gruesome. What makes their impact even more so is the second aspect that makes this film a tough watch — genuine animal slaughter.

Deodato, for whatever reason (and he has given many), decided to have his cast kill real animals on screen. A couple did not die easily, meaning animals suffered for his film. That decision is of very dubious artistic value, no matter what excuses he offers, and no matter that all the slaughtered animals were consumed by the extras he hired to portray the villagers. From a filmmaking standpoint, it succeeds very well in priming the audience for the simulated gore. I am glad that this method hasn’t become widespread in horror films.

Deodato was also something of a tyrant on set, pushing his cast and crew to film scenes with which they were uncomfortable, and that comes through on screen.

All of this mixes together into a horrifying experience for an audience. But, I’ve seen this film a couple of times now, meaning I’ve grown more accustomed to its visual impact. I’m no longer overwhelmed and can see more of the picture than on a first viewing. The atmosphere in this film is spectacular. The music of Riz Ortolani, soaring and somewhat romantic, exists in stark contrast to the events on screen, yet it works. The cinematography of Sergio D’Offizi is brilliant. Scenes with Monroe were shot in 35mm, while the student film is shot in 16mm, providing a subtle contrast between the two. Deodato’s storytelling and pace are excellent. Had this film’s violence been more conventional, there would be nothing controversial about this film, and it might be more highly regarded. But then, it wouldn’t be Cannibal Holocaust, would it? Deodato set out to make a movie that would shock audiences. He succeeded, probably beyond his wildest expectations.

This is one of those films that attracts diehard fans of horror, and the curious, alike. Many will hate it. Many will be outraged by it, whether it’s by the exploitative depictions of rape and mutilation, or the actual killing of animals. Despite this, Cannibal Holocaust is a boundary-pushing work of film. If it can’t be celebrated for that, it can at least be recognized for it.