Lisa and the Devil, the 1973 film from Italian auteur Mario Bava, has become one of his more renowned films in the last couple of decades. I first saw it around twenty years ago with a roommate who was watching it for her film class at NYU. Upon release, though, it was a butchered product, with a framing story shot and added after Bava delivered his cut. Of this film, which had been released under the title of La Casa dell’esorcismo (House of Exorcism), Bava said, “La casa dell’esorcismo is not my film, even though it bears my signature. It is the same situation, too long to explain, of a cuckolded father who finds himself with a child that is not his own, and with his name, and cannot do anything about it.”

Lisa and the Devil, the 1973 film from Italian auteur Mario Bava, has become one of his more renowned films in the last couple of decades. I first saw it around twenty years ago with a roommate who was watching it for her film class at NYU. Upon release, though, it was a butchered product, with a framing story shot and added after Bava delivered his cut. Of this film, which had been released under the title of La Casa dell’esorcismo (House of Exorcism), Bava said, “La casa dell’esorcismo is not my film, even though it bears my signature. It is the same situation, too long to explain, of a cuckolded father who finds himself with a child that is not his own, and with his name, and cannot do anything about it.”

That’s some pretty strong language. But, he wasn’t referring to the film that was eventually released as Lisa and the Devil. He was referring to a cobbled-together mess insisted upon by the film’s producer, Alfredo Leone, who wanted a whole bunch of exorcism-related material added to an already completed film in order to cash in on William Friedkin’s Exorcist. This year’s Horrorshow is not concerned with that movie.

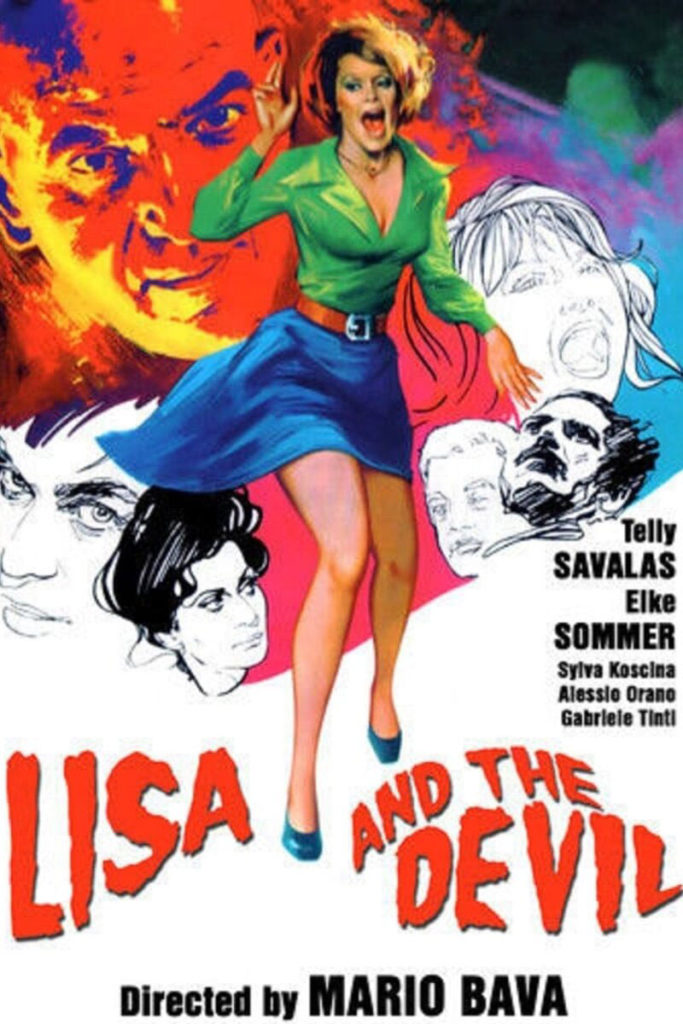

Lisa and the Devil follows Elke Sommer as Lisa, a tourist who gets lost in the wandering, narrow streets of old Toledo, Spain. She hitches a ride from a rich, married couple, Francis and Sohpia Lehar (Eduardo Fajardo and Sylva Koscina), and their chauffeur, George (Gabriele Tinti). The Lehar’s old limo breaks down in front of a villa, and they are invited in by the Countess (Alida Valli) and her son, Max (Alessio Orano). In a bit of stunt casting, the Countess’s butler, Leandro, is played by Telly Savalas.

Savalas was a mercenary in this flick, and loving every minute of it. There’s nary a spot in which he appears where his joviality and innate sense of mischief was not stealing the scene. The pièce de résistance was his continual sucking on lollipops, just like the character he made famous in Kojak. I don’t know whose idea it was to mirror the role he played on TV, but it was another tongue-in-cheek aspect of a character who is not meant to be taken seriously.

There is intrigue at the villa. George is carrying on an affair with Sophia, and Francis knows. Meanwhile, Leandro is carrying around a mannequin that occasionally comes to life and torments Lisa. His name is Carlo (Espartaco Santoni). He’s the Countess’s deceased husband, and he has a connection to Lisa that isn’t explained until near denouement. Viewers familiar with this kind of story will know where the plot is going. Lisa is a doppelganger for Carlo’s lost love, and her presence at the villa has set in motion many, many dastardly things.

For the Countess’s part, she knows all that is going on, and dreads the inevitable conclusion. Her son is a headlong participant in the events of the film, with more than a few secrets of his own. And hovering over it all is Leandro, a seemingly disinterested character, a servant who is there in every pivotal moment, but, being a servant, safe to ignore. Or, is he? Yeah, it’s that kind of story.

And then there’s Lisa. If Leandro was hovering over it all, Lisa was drifting through it all. Events happen around and to her, and although she is bothered by what she experiences, it’s never enough to make her active in trying to repel any danger she’s in, or to flee from it. The vacant look on Sommer’s face is reflective of an audience member’s, who might be trying too hard to make sense of Bava and Leone’s convoluted plot.

After many twists and turns, everything is explained in climax, and then Bava passes over multiple fine opportunities where he could have ended the film, and instead throws some more silliness at the viewer.

This is a film that has been rehabilitated over the years, but no one is out there rating this a ten out of ten, and for good reason. That plot is just too difficult to rate as great storytelling, nor did Bava seem willing to give it more than passing attention. What Bava was really focused on was making a movie that looked fantastic. He and cinematographer Cecilio Paniagua crafted every shot meticulously, to the point that they used, or overused, the same techniques again and again. If one likes zooms and shots that switch from focus to out of focus, one will get those shots aplenty. My favorite shots in the film are when the two photographers treated the set like the stage at an opera, with colors that contrast almost to the point of garishness. There’s a painterly, dreamlike feel to much of the movie that makes sense once all is revealed.

At its core, Lisa and the Devil is a gothic horror film. Remove all the modern accouterments, of which there are not many, and the film slips easily into the 19th century, almost to the point one wonders why Bava bothered having any contemporary scenes at all.

A bit showing off, a bit confused and muddled, there are reasons that Lisa and the Devil is lauded, dismissed, and studied. It’s a film made by a master, indulging in all things Bava-esque. I recommend it for fans of horror and fans of international cinema alike, as worth the experience. It’s not the easiest watch, but it is a film that will stick with one for some time.