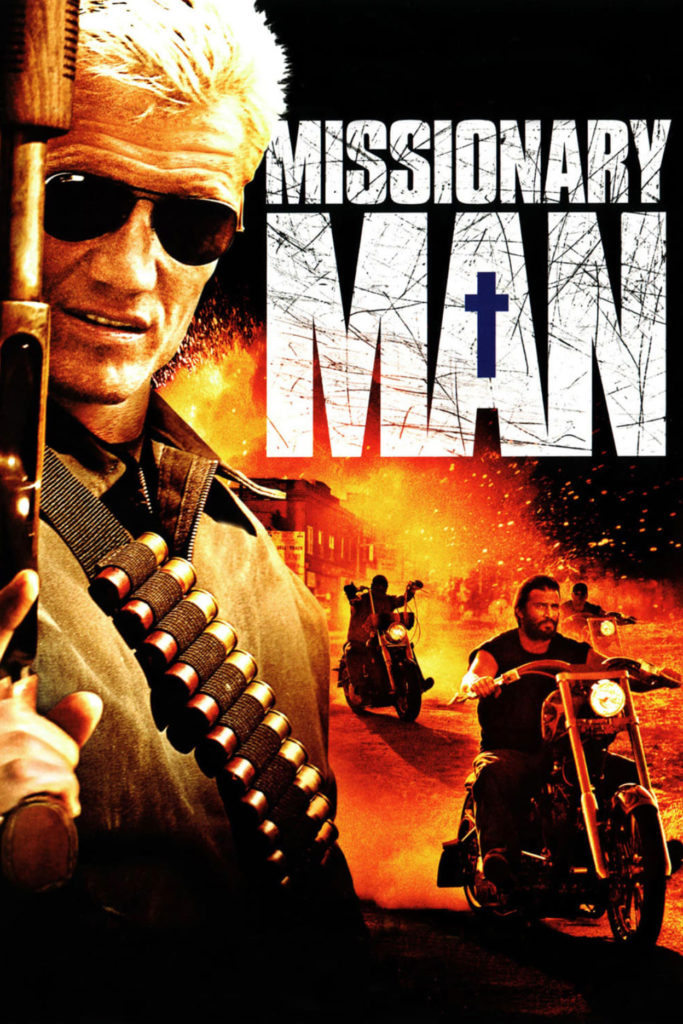

What joy for Missile Test, as today we feature another film that b-movie action hero extraordinaire Dolph Lundgren not only starred in, but also wrote (with Frank Valdez), and directed. The writing couldn’t have been too taxing, though, as Missionary Man is a contemporary retelling of Pale Rider, the 1985 Clint Eastwood western.

Lundgren stars as Ryder, a mysterious biker who has a penchant for tequila and bible verses. He rides into a small town in southern Texas (played to effect by the city of Waxahachie) in time for the funeral of JJ (never seen on screen), a Native American tribal council member who was killed by the dastardly John Reno (Matthew Tompkins).

Reno is the town’s resident jerkoff/crime lord, and he killed JJ because JJ opposed a plan to bring a casino to tribal land without using the resulting profits in a wise and ethical way. Now Reno has a stranglehold on the town, and only Ryder has the guts to do anything about it.

Ryder does so with his fists and feet until the final act, cutting swaths through every unlucky henchman Reno sends his way. After about an hour of this, Reno is so fed up he calls in help from the north in the form of Jarfe (John Enos III) and his gang of gun-toting outlaw bikers. What follows is the bloody climax viewers expect.

Up until then, though, Missionary Man has long stretches that will be somewhat tedious to not just viewers who have seen Pale Rider, but to just about anyone who has seen a western with a lone hero.

The characters are stock and part of the rote nature of the film. There’s the murdered homesteader in the form of JJ, his distraught significant other or sister character (Kateri Walker), and her orphaned kids (Chelsea Ricketts and John D. Montoya). There’s even the sassy saloon owner (Morgana Shaw), burnt out sheriff (James Chalke), and  town addict (Jonny Cruz).

town addict (Jonny Cruz).

There’s nothing wrong with piling up all these well-worn clichés and character tropes. It’s actually useful in a film more concerned with showing Lundgren’s jawline than doing any significant character development. The problem is that none of this shorthand is done well. The film lurches on, coloring within the lines, all the way up until that final act before the pace picks up.

Speaking of color, what viewers will notice most about this film is how it was shot. According to the internet, so it must be true, when the transfer of this film was made for DVD and streaming, the color got fouled up. The result is a grainy film washed of so much color that it’s an effective simulation of what it’s like to live with color blindness. Whoops.

Lundgren has around two moods for the characters he plays, depending on the film. He can be either jovial and violent, or grim and violent. He went with grim for this picture. Had he been in a more playful mood, perhaps he could have written Ryder to be mute for the entire film. As it is, the only important actions his character takes is when he kicks ass. His actual motivations are murky, and explained in a manner less effective than the Preacher in Pale Rider, but no less supernatural.

What Lundgren and company have made is a movie that is a waiting room for its own final act. It’s a neat idea to update Pale Rider as a pseudo-outlaw biker flick. It’s a story type that’s such a part of the American zeitgeist that it should be harder to screw it up than do it competently. But, as movies prove again and again, pace is not easy.

There are far worse films in Lundgren’s oeuvre, and this flick does seem to have been made with care. That said, any film that spends this much time wandering around and paying only token attention to the story it’s cribbing can’t be saved by upping the blood and guts in the finale.

Missionary Man falls into the lower half of the Watchability Index, landing with a thud and displacing Paradise Alley at #400.