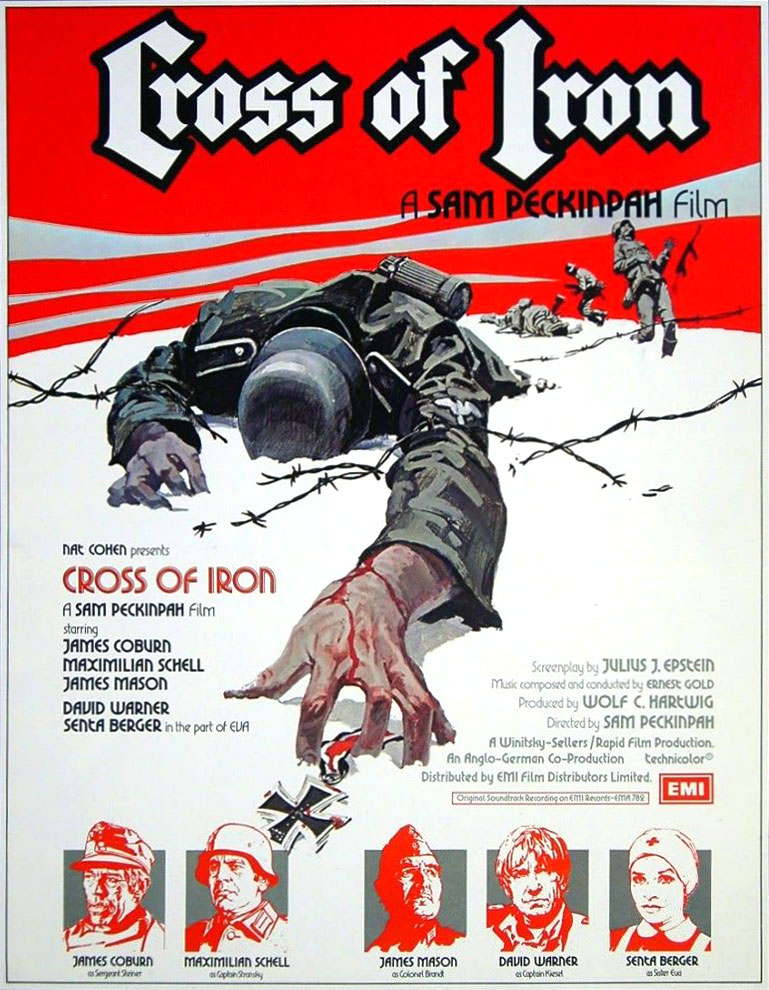

Cross of Iron, Sam Peckinpah’s entry into the World War II genre from 1977, is a study in two-dimensional characterizations. Well-written, well-acted, and well-directed, this perfect storm of effort on the part of all involved results in a bloody violent film whose characters barrel their way through without nuance, relying on the audience to fill in the blanks. How successful the film is, therefore, depends on a viewer’s understanding of war, or what they think they understand.

Cross of Iron tells the story of Sgt. Steiner, a Wehrmacht soldier in the Crimean during World War II, played by James Coburn. Steiner is a disillusioned fellow. His hatred of war, all the killing and dying, is apparent from the first moment he appears on screen. He’s gruff and unshaven. His eyes are world-weary and mean. To be placed under their stare is to wither beneath his experiences. As if that weren’t enough, he wears a chest full of medals, confirming all our suspicions that this man is, also, a hero. Maybe a one-time true believer, but the horrors of war have turned him into the figure we see before us today. Still brave, still lethal, but far from the days when there was any glory to what he’s doing.

Steiner leads a small, battered platoon of veterans during the Wehrmacht’s great retreat following defeat at Stalingrad. Platoon is too strong a word. All that is left Steiner is something resembling a squad, but such is war. They are akin to their leader, unsure of their continued survival, resigned to their place in the war, and, if possible, even more filthy and wretched than Steiner.

The Red Army is the ever-present menace in Cross of Iron, but the main antagonist is not Soviet. Rather, it is Captain Stranksy, played by Maximilian Schell, a German officer plucked from the Prussian aristocracy, recently arrived on the Eastern Front to find glory and make a name for himself. Stransky is the polar opposite of Steiner. Where Steiner sees no point to the war, Stransky finds opportunity. Where Steiner shows compassion and honor, misplaced  attributes in war, to be sure, Stransky is naught but cold and mischievous. The only thing they seem to agree on is a mutual distaste for the Fuhrer, but one has to wonder how much that has to do with the plot, and how much it has to do with real world politics and box office receipts.

attributes in war, to be sure, Stransky is naught but cold and mischievous. The only thing they seem to agree on is a mutual distaste for the Fuhrer, but one has to wonder how much that has to do with the plot, and how much it has to do with real world politics and box office receipts.

Because of these two main characters, it is inevitable that the great conflict in Cross of Iron is not between two warring armies, but between two clashing personalities, and there is a death toll. Rising and rising throughout from the midpoint of the film, the final climax is ambiguous, but satisfying; a big chunk of mystery for the audience to chew after having been fed rather predictable fare for the previous two hours.

Predictable, but good. Peckinpah is one of those filmmakers whose works can be identified after only a moment’s worth of viewing. All his trademarks are present. Cartoonish levels of violence, long sequences of gun fire, slow motion shots of bullet impacts and flailing bodies, etc. Peckinpah honed these skills on Westerns, and he never completely let go of that genre. The setting for Cross of Iron may be different, but the film is every bit as much a Western as The Wild Bunch. Why that works so well in Cross of Iron, and The Wild Bunch, for that matter, is due to the fact that war is war, and death is death. Peckinpah is more a master of violence than a master of cowboys and Indians, so Cross of Iron fits right into his oeuvre.

As mentioned earlier, the characters that populate Cross of Iron are two-dimensional — simplistic, even. What depth there is to them is supplied exclusively by the audience. Normally, shallow characterizations would be hurtful to a film. Not so here. In Cross of Iron, the mystery of their condition, how these men came to be this way, engages the viewer. We root for Steiner, we boo Stransky. We picture them out of uniform, away from the hell that surrounds them, back in the lives they left. At one point, we even get a brief glimpse of the world away from the bunkers and the shelling. It’s frustrating how short and tantalizing it is. We are watching men made what they are by their surroundings, making the war itself more than just a periphery character. Without it, Steiner and Stransky would have no motive, no basis for their war against each other. And finally, in the end, the film breaks away from itself, into the unknown.