Marines can be grossly immature. In point of fact, that’s a generalization which can be made about members of all the four services, but especially Marines. A young grunt’s slang and mannerisms are by design repugnant, frequently homophobic or faux homoerotic, and sometimes racist. The young Marine is the very personification of testosterone run wild, machismo fueled by hormones thrown all out of whack by age, temperament, and environment. The young can be crazed and inelegant all on their own, but military training hones these traits to a fine edge, a bizarre side effect of turning what was a boy into a highly efficient killing machine.

I’ve encountered people like this after they’ve put in their four years and get released back into the world. There is always an adjustment period wherein the new civilian has to relearn acceptable civilized behavior. No longer is it okay to engage in graphic conversations about masturbation or defecation while sitting at meals in polite company. No longer is it okay to jokingly, or not so jokingly, openly question another person’s sexual orientation as it relates to that person’s willingness or unwillingness to engage in shenanigans, get blindingly drunk, etc. In many ways, whatever growing up a young man does between the ages of 18 and 22 is twisted in a completely different direction while enlisted in the military. These men are given responsibilities far beyond what a typical college student is entrusted with — responsibility over millions of dollars of equipment, and in times of war, over life and death. But emotional maturity can regress. It would be tragic were it no so damned funny.

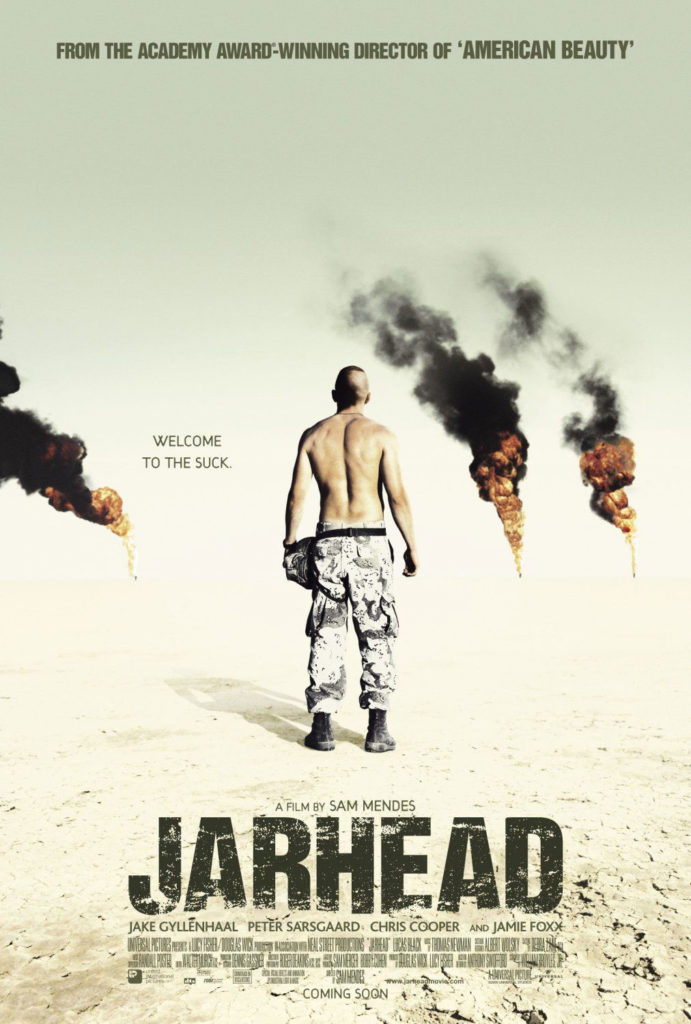

Sam Mendes’ Jarhead and the HBO miniseries Generation Kill (both based on firsthand experiences in the Gulf and Iraq Wars) thrive on repulsive language. “Dick-skinners,” “buck-toothed, cross-eyed, sister-fucking hicks,” “cum dumpsters,” and MOPP suits “that smell like four days of piss and ball sweat” are only a small peek at the trampling the English language takes from the grunts in these two pieces. If a viewer is not prepared to see America’s heroes speak in this manner,  and often behave to match, it can be jarring. These Marines are a long way from the square-jawed automatons seen marching in formation on parade grounds. But look again. They’re the same people. If a person has any sort of mythical regard for these warriors, they would be wise to dispose of those notions as quickly as possible. In language and mannerisms, including the addition of military-specific jargon, Jarhead and Generation Kill nail the post-Vietnam military persona.

and often behave to match, it can be jarring. These Marines are a long way from the square-jawed automatons seen marching in formation on parade grounds. But look again. They’re the same people. If a person has any sort of mythical regard for these warriors, they would be wise to dispose of those notions as quickly as possible. In language and mannerisms, including the addition of military-specific jargon, Jarhead and Generation Kill nail the post-Vietnam military persona.

It’s not all grunts that act this way, in reality or on film, but to pretend they don’t exist would be to infringe on the realism audiences demand of today’s onscreen warfare.

Jarhead is a war film in that its characters are in the military, and it takes place during a war. But, that war is the abbreviated ground campaign of Operation Desert Storm, one-hundred hours of swift action in which half of coalition deaths in action were not from enemy fire, and most damage to the enemy was done from the air. As such, the Gulf War’s bloodthirsty Marines, for the most part, weren’t able to “get some.”

Jarhead follows Marine sniper Anthony “Swoff” Swofford, played by a beefed-up Jake Gyllenhaal. Additional performances of note were turned in by Peter Sarsgaard as Swoff’s spotter Troy, and Jamie Foxx as the gruff career Marine, Staff Sergeant Sykes. Swoff hates being in the Marines, or “the suck,” and after becoming inescapably immersed in the Saudi desert while waiting for the war to start, begins to act out in desperation from the unending boredom. That’s a good thing for audiences, because if Swoff and his fellow Marines had succumbed to the boredom of half a year in the middle of nowhere, the entire second act of the film would have been a disaster. Swoff becomes increasingly erratic, only to snap out of his funk when the marching orders come through. All the piled up bullshit instantly disappears as the Marines pour over the berm into Kuwait.

The story of the Gulf War cannot be told from the perspective of enlisted men without dealing with the interminable wait for the shooting to start. Director Sam Mendes handles the buildup to war deftly, touching on all the necessary points of the absurd that are a part of everyday military life while deployed overseas, from the endless propaganda, the overzealous insistence on adhering to pointless rules and orders, to the messes caused by unfaithful spouses and girlfriends back home.

The final act feels short, like the war itself in relation to the buildup, and has a ridiculous scene with Marines digging foxholes while it’s raining crude oil from destroyed wells. This act ends suddenly, and could leave a viewer unsatisfied at the outcome, but this is not a movie about valor or heroism, or the hopeless few holding out to the last man against unstoppable enemy hordes. Jarhead is a grunt’s story, and while it does fall occasionally into military myth and urban legend, its central focus, Swoff and his experience of war, is what makes it work. Also, that is what turns so many viewers off.

Generation Kill covers the initial invasion of the Iraq War in 2003, and this much more expansive subject gets more than seven hours of total screen time. Little of it is spent on the buildup before invasion, perhaps recognizing how ably Jarhead covered similar material. Instead, there is just enough to introduce the ensemble cast before they roll into Iraq.

Where Jarhead was strictly told from the perspective of Swoff, who also penned the source material, Generation Kill came from the mind of a reporter, Evan Wright (adapted for television by David Simon, Ed Burns, and Wright), played by Lee Tergesen. As such, that character plays the minor role of witness more than participant, leaving the war to the Marines. It reminds me of writer Michael Herr’s observation of his role in Vietnam. When one soldier exclaims that American troops were there solely to kill gooks, Herr writes, “[That] wasn’t at all true of me. I was there to watch.” As unsettling as that sounds, denying its accuracy would be futile.

Generation Kill follows members of a Force Recon battalion as it invades Iraq and pushes its way north. There isn’t much combat, being more character driven, but what there is, is brutal. The Iraqis, in reality and dramatization, were completely overmatched during the invasion, and Generation Kill shows this. Jarhead did well with the absurd, and spent little time on the cruelty of war. Generation Kill can wallow in the confusion, bullshit, and senseless death which accompany armies on the move. It tries hard not to moralize too much, but it does contain graphic depictions of tragic mistakes which end with Iraqi civilians lying dead by the side of the road. We’re all familiar with the imagery by now. Generation Kill shows how it happens.

The series may be partly the result of the political environment in the country. It signals that we have somewhat been confronting the consequences of our choices these past years, even as the war recedes from view. World War II dramas are noticeably thin on conscience-churning depictions of warfare. Vietnam films revolve around them. Generation Kill strikes a balance, keeping the tale human while not condemning any Marine for anything he may have done.

The Gulf War was quick enough to be a sideshow in American history, leaving little reason to dwell too long on it. The Iraq War, by contrast, destroyed the credentials and effectiveness of an entire presidential administration. Those reverberations are present throughout Generation Kill. We watch the great American war machine in all its cluelessness as it dismantles Iraq, and we know what happens next. Thank goodness for those foul-mouthed Marines, otherwise the weight of Generation Kill could be crushing.

The ensemble cast can be hit and miss, as can the dialogue. The best performances also happened to be those that got the most screen time. These included James Ransone as Corporal Ray Person, who provided welcome relief from tension; Alexander Skarsgard as the rock-like team leader Sergeant Brad Colbert; Chance Kelly as the battalion commander ‘Godfather’; and Stark Sands as the youthful yet competent Lieutenant Fick. There were few bad readings from the cast throughout the life of the series, but the weak links are very easy to spot.

Another weakness is the endless driving. The invasion was the ultimate example of mobile warfare. Consequently, the Marines spend a great deal of the series traveling in Humvees, to the point the series becomes an extended road movie with high caliber weapons. Seven episodes at an hour-plus each is quite a commitment to make to Generation Kill, especially as it has far less twists and turns than the narrative fare that populates much of television today. Burnout can begin to set in halfway through, especially when the script calls for yet another depiction of the fine military art of hurrying up and waiting.

Generation Kill is entertaining, yet flawed. There’s a distance between viewer and character that is never quite overcome, much the result of being adapted from an outsider’s point of view. Where it finds its success is in its portrayal of the misplaced hubris of March and April 2003. It is a war story that stops perfectly short of being an indictment. It does a fine job showing who fought, and the transformations many of them made after they were unleashed on Iraq. For a small screen effort, it goes about as far as is possible.