Black Hawk Down is perhaps the simplest movie I’ve ever viewed, and also the most complicated. The United States intervention in Somalia is a footnote in America’s foreign policy history, but it is quite weighted, to the point that a student of recent American politics ignores it at their own peril. The initial American operation in Somalia, Operation Provide Relief, part of UNOSOM I (United Nations Operation in Somalia I), began in August 1992 as a response to the massive amount of killing and humanitarian suffering throughout the country. It was followed by UNITAF (Unified Task Force), also known as Operation Restore Hope, which lasted from December 1992 to May 1993. During that time, the United States suffered 43 killed and 143 wounded, but was able to increase the security of much of the country. After the mission ended, however, the peace did not last, as the warlords reasserted their control and chaos took hold once again. This led to UNOSOM II, Operation Gothic Serpent, and ultimately to the Battle of Mogadishu.

Black Hawk Down deals with a bad day for the U.S. military. On October 3, 1993, Task Force Ranger, comprising elements of the 3rd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, C Squadron of Delta Force, the 1st Battalion of the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR, also known as the Night Stalkers), along with Navy SEALs and Air Force Combat Controllers, infiltrated a hostile area of Mogadishu, known as the Bakaara Market, with the aim of apprehending senior members of warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid’s organization. The operation was supposed to be over in less than an hour, maybe a little longer. The next day, after the involvement of Task Force – 10th Mountain Division and UN soldiers from Malaysia and Pakistan, Task Force Ranger was able to fight its way to safety, after suffering 18 dead, 73 wounded, and one captured, while inflicting anywhere from 2,500 to 4,500 Somali dead and wounded. The raw numbers suggest a victory for American and UN forces, but it was a Pyrrhic victory at best. Body counts do not tell the story by any stretch of the imagination. It was a brutal engagement whose aftermath was played out on the evening news, as scenes of enraged Somali mobs dragging the stripped corpse of an American soldier through the streets of Mogadishu showed that despite the blood spilled, the Somalis had seized the upper hand in public opinion. It wasn’t long before President Clinton pulled the  plug on the operation. Seven years later, presidential candidate George W. Bush was clearly referencing the Somali operation when he declared that if he were president, errant adventures in nation building would not be part of his administration’s foreign policy.

plug on the operation. Seven years later, presidential candidate George W. Bush was clearly referencing the Somali operation when he declared that if he were president, errant adventures in nation building would not be part of his administration’s foreign policy.

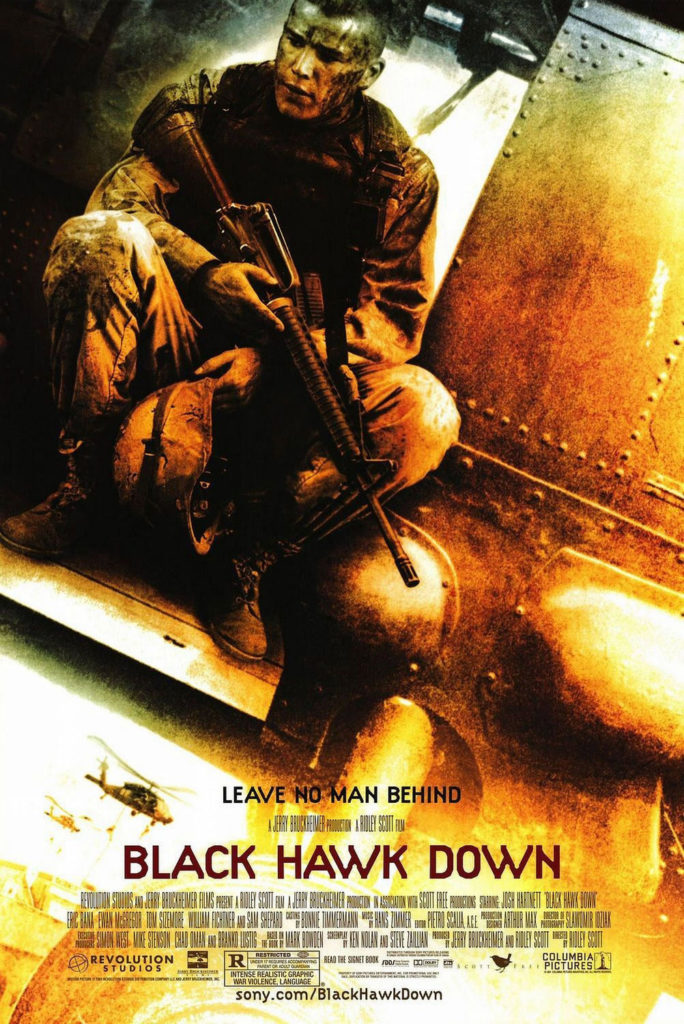

Based on the book of the same name by investigative reporter Mark Bowden, Black Hawk Down focuses on the travails of Task Force Ranger during the battle. Condensed, dramatized, and fictionalized, Black Hawk Down is unapologetically patriotic, choosing to emphasize the struggles and sacrifices of the American combatants while only lightly touching on the complicated interplay of the politics which led to the battle in the first place. What depth the book had, especially in its interviews with Somali witnesses and participants in the battle, has been excised. In its place, we see the battle from the perspective of the American task force, all Somalis reduced to inhuman caricature — bloodthirsty savages lacking in civilization and respect. Also, the film is presented as a glorified account of war, despite the graphic horror of the combat. This is a travesty, and surprising considering the film was directed by Ridley Scott, an Englishman, but not surprising considering one of the producers was Jerry Bruckheimer, who wouldn’t know nuance if it came up and nibbled on his ass. That is a shame, because presenting the Battle of Mogadishu as an ultra-patriotic set piece is a disservice to fact. Yes, our men displayed profound bravery and skill in battle, but separating it from the reasons the fight happened in the first place cheapens the story.

That being said, as a war film, it delivers. The battle takes up more than half of the running time, to the point that a viewer can get weary of all the gunfire. It doesn’t spare the details of some of the more gruesome deaths, showing how these men died in gory fashion. From Delta operator Tim ‘Griz’ Martin being torn in half by an RPG to Ranger Sergeant Dominick Pilla being shot through the head and instantly killed, part of the powerful message of the film is that people die horrible deaths in a firefight. Not unexpected, but certainly random, it portrays the sense that there is no way to predict who lives and dies. Such consideration was not extended to the Somalis, who die faceless, nameless, and equally as brutal deaths throughout in greater numbers, but the film makes no pretense that they were worth anything.

The film does a fine job of portraying the fog of war, where well-considered plans become useless almost immediately, and the flow of vital information can be delayed and rendered just as useless by layers of command and control. Indeed, it was not just the Somalis that contributed to the protracted nature of the battle, but the relay of out of date information to forces on the ground presented as up to date instructions and intelligence.

While the film is overly biased to the American mission, there were genuine moments of bravery by American forces in the battle, and individual soldiers, whose story is told on screen. Among the most effective is the story of Master Sergeants Randy Shughart and Gary Gordon, Delta snipers who volunteered to take on certain death by securing the crash site of Super 64 — one of the Black Hawk helicopters shot down by Somali rebels — before reinforcements could arrive. The two of them were killed, and awarded Medals of Honor posthumously. Their tale is confounding to anyone with a sense of self-preservation. In reading the book and viewing the film, it was clear that their chances of survival were practically nil, yet they decided that aiding helpless survivors of the crash on the ground was more important than their lives. Words are hard to come by.

If a person knows nothing of our misadventure in Somalia, maybe they can view the film in a different light. I don’t think it works in that way as pure entertainment, even though it tries to be that. But if a viewer has a sufficient amount of background information, it is impossible to separate the simplicity of the film from the morass that was reality.

Worth further mention is the ensemble cast. This film was loaded with experienced actors alongside actors who would go on to greater fame. Tom Sizemore and Sam Shephard, as Lt. Colonel Danny McKnight and Major General William Garrison, respectively, were the most seasoned veterans, each having a fair amount of high profile roles in their resumes. Newer stars included Ewan MacGregor as Specialist Grimes, Josh Hartnett as main Ranger protagonist Sgt. Eversmann (a composite of Eversmann’s actual experiences, and others’), and Ewan Bremner as wily SAW gunner Shawn Nelson. There were also prolific character actors, faces that many moviegoers would recognize right away if they saw them. These included William Fichtner and Kim Coates as members of Delta Force, Jeremy Piven and Ron Eldard as Black Hawk pilots, Jason Isaacs as Ranger Captain Steele, and Zeljko Ivanek circling above the battle in a chopper directing troop movements. As for the young ones who have gone on to greater fame, look quickly for Orlando Bloom as Private Blackburn, Eric Bana in an extended role as the main Delta protagonist Norm Hooten, and Tom Hardy as another SAW gunner. There is, without a doubt, a plethora of talent in this film. It’s only the banalities of the screenplay that keep them from shining as brightly as they are all capable.