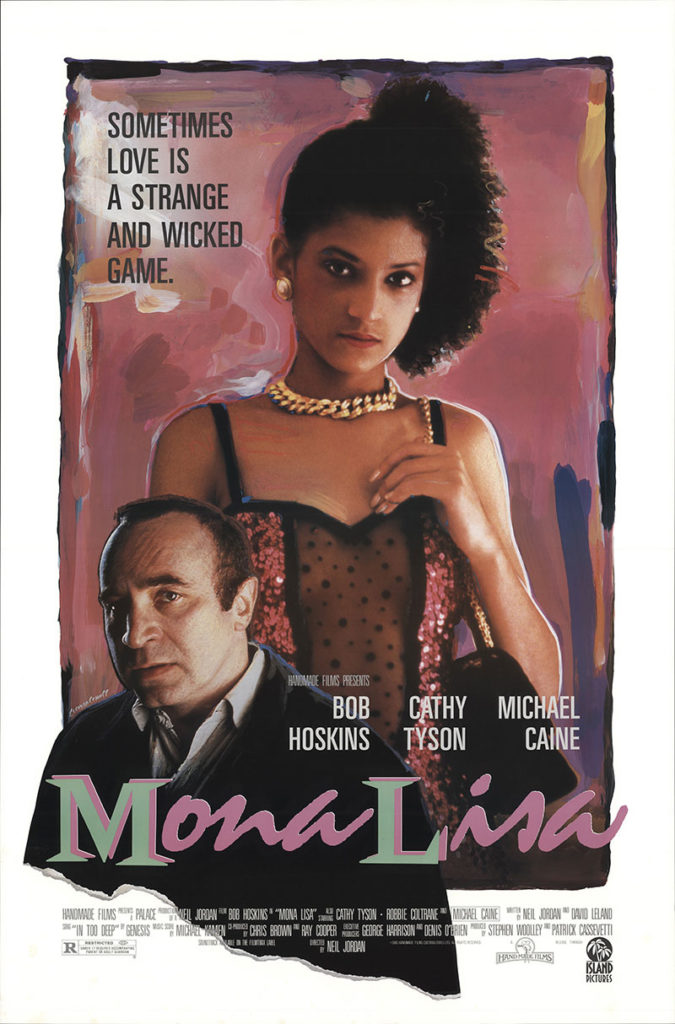

Mona Lisa isn’t a typical British gangster film. Many of the hallmarks are there, to be sure. Gritty London scenery, almost impenetrable accents, and Michael Caine and Bob Hoskins. But many of the things a viewer expects from the plot of a British gangster film are absent. There’s no big heist being planned. There’s no grisly murder to revolve the story around. There’s violence at times, but it isn’t the gratuitous kind. It doesn’t rule the film. When it comes, it’s a necessary outcome of the story. Mona Lisa tells a story wrapped within a recognizable genre, but it uses that genre as a tool to tell the tale of a complex personal relationship.

Bob Hoskins plays George, a convict just released from prison after serving a seven-year bit. The audience is never told why he went to prison, but it doesn’t matter. George himself doesn’t like to talk about it, evading the subject or lying outright when asked about his past. The things George keeps from those he knows he also keeps from the audience, making his character more real.

After a disastrous visit to his estranged wife and child, George finds work through his old employer, Mortwell (Michael Caine), chauffeuring a call girl by the name of Simone (Cathy Tyson). It is the interplay of George and Simone that ignites the plot.

Simone is desperate to locate a teenage hooker she used to live with before she broke away from her pimp, Anderson (Clarke Peters), and she enlists George’s help. He’s reluctant, but agrees to delve into the rated-X underworld of 1980s London to find the missing girl. Why he does so is obvious. He’s falling for Simone, but  director Neil Jordan handles the delicate dance between Simone and George with such effectiveness that a viewer can flip back and forth between Simone’s and George’s view of the situation with whiplash speed. She’s using him, or maybe she’s not using him. George is naïve and gullible, or he has too much street smarts to fall for her ruse. He’s a good man trapped in a bad game, and will do what’s right. The only thing missing here is cold calculation on the part of George. He’s just not capable of it. He is a dumb man. Noble, but with a head full of rocks. His lack of intelligence would seem to point to Simone as a dreadful manipulator — but is she? She tells tales of her clients falling in love with her, a blaring danger signal, but she could just as easily be the age-old hooker with a heart of gold.

director Neil Jordan handles the delicate dance between Simone and George with such effectiveness that a viewer can flip back and forth between Simone’s and George’s view of the situation with whiplash speed. She’s using him, or maybe she’s not using him. George is naïve and gullible, or he has too much street smarts to fall for her ruse. He’s a good man trapped in a bad game, and will do what’s right. The only thing missing here is cold calculation on the part of George. He’s just not capable of it. He is a dumb man. Noble, but with a head full of rocks. His lack of intelligence would seem to point to Simone as a dreadful manipulator — but is she? She tells tales of her clients falling in love with her, a blaring danger signal, but she could just as easily be the age-old hooker with a heart of gold.

Hoskins just kills it in his portrayal of George. He’s a sympathetic oaf, a poor man that a viewer just can’t help but root for. His past, his temper, and his ignorant racism all work against him but it all seems to be the product of nurture over nature. He has been made this way by circumstance, and his true character just needs a good excuse to blow all of the nastiness away. And that good excuse is Simone.

Cathy Tyson is all but unrecognizable to audiences here in the states. Other than Mona Lisa, the only other film viewers may remember her from is the dreadful Wes Craven flick The Serpent and the Rainbow. Since then, she’s been mostly a fixture on British television. Simone looks to be the role of a lifetime for Tyson. The film would have failed if Neil Jordan had not been able to find a worthy compliment to Bob Hoskins. What I’ve described would seem to require a real 10, a star of unquestioned talent and beauty, unique in cinema. Let’s not get carried away. Tyson is not that. She is pretty enough for the role without going over the top. She plays mysterious well enough to seem genuine. Jordan, however, recognized that although her character was essential to the story, there is only one main character in Mona Lisa, and it is not Simone. Her long absences in the film only add to her worth.

As things move along, George finds himself in conflict with everyone he knows in the underworld, and in the end it is revealed whether or not it was all worth the effort and the danger. I won’t reveal that here. The denouement is the very essence of the film, and worth the wait.

There is one other thing worth mentioning. The 1980s were a horrible time for popular music, and there were instances when the insanity made its way into cinema. There’s a dreadful stretch in Mona Lisa when the Genesis song In Too Deep is used as background while George is engaged in his search. It’s an awful song, and manages to derail the film for the entire time it’s playing. It’s such a jarring event that it has to be made known to any potential viewer, in order they be assured it does not signal the death of the film itself. Get through it. The fine film you were watching continues on the other side.