Gritty New York City cop dramas are stylistically different from gritty Los Angeles cop dramas. It’s only partly due to setting. It would be hard for a film to ignore the differences between the coasts, but as far apart as the Eastern Seaboard and SoCal are, geographically and culturally, these differences are not what set cross-continental police flicks and television series apart. Just doing a loose word association, when I think NYC cop drama, my first thought is Law & Order and all of its iterations — police procedurals that follow detectives. After that I drift back to films from the past like The French Connection, Serpico, Fort Apache the Bronx, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Across 110th Street, even Bad Lieutenant. These films represent my own personal biases, but they all adhere to a palate of sorts that is broadly representative of New York City cop films.

Gritty New York City cop dramas are stylistically different from gritty Los Angeles cop dramas. It’s only partly due to setting. It would be hard for a film to ignore the differences between the coasts, but as far apart as the Eastern Seaboard and SoCal are, geographically and culturally, these differences are not what set cross-continental police flicks and television series apart. Just doing a loose word association, when I think NYC cop drama, my first thought is Law & Order and all of its iterations — police procedurals that follow detectives. After that I drift back to films from the past like The French Connection, Serpico, Fort Apache the Bronx, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Across 110th Street, even Bad Lieutenant. These films represent my own personal biases, but they all adhere to a palate of sorts that is broadly representative of New York City cop films.

Across the farmlands, the plains, the mountains and the deserts, Los Angeles has been building its own mythos regarding the LAPD on film. After decades following the cop as superman (think Lethal Weapon, Cobra, etc.), that model looks set to be replaced by episodes of Cops. I’m not joking. Some of the best work regarding LAPD officers of late hasn’t involved huge explosions and guns that never run out of ammo. It hasn’t been the lone detective doggedly pursuing the impossible murder case. It hasn’t been buddy movies. It’s been the uniformed officer.

The progenitor of the model has to be Colors, Dennis Hopper’s film from 1988 about cops and gangs in South Central L.A. That film is a quarter of a century old, but it’s look and feel has been carried on to effect in television series like Southland and The Shield, and films such as Crash.

There are so many films with cops that take place in both cities it’s impossible to say there’s now a defined set of rules, but it can be pictured as a Venn diagram, with many overlapping ideas, some remaining unique to the location.

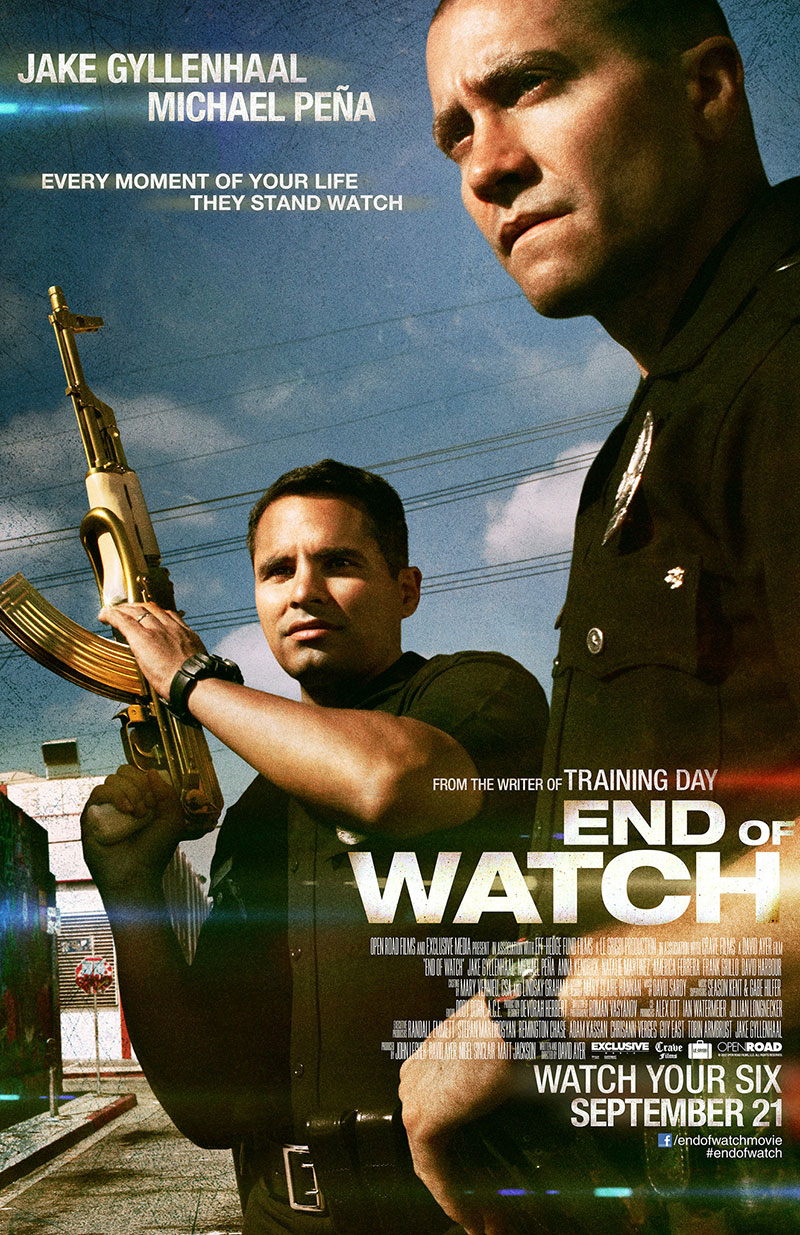

Last year saw David Ayer’s End of Watch, which he both wrote and directed. Ayer gained fame by penning Training Day, kin to this film in many ways but focusing on plainclothes police. End of Watch follows patrolmen Taylor and Zavala (Jake Gyllenhaal and Michael Pena), partners who work a tough part of the city. The film is a long, but not slow, build as we see them respond to everyday calls that over the course of months end up becoming something big. The two are aggressive police officers. They have a bit of cowboy to them but they don’t seem all that reckless. They’re just young and cocksure. Things have obviously never turned against them, yet.

Centuries of drama have taught us that they will be punished for their hubris (so did the trailer, quite frankly), but Ayer is very effective in building the tension early and maintaining it until the end. You know these two are going to kick down the wrong door eventually, you just never know, ever, which door that’s going to be...until about ten minutes before the climax when we see the bad guys getting ready. It’s good storytelling, not perfect. But still, the set pieces that make up Taylor’s and Zevala’s life as cops are very compelling.

Another area where Ayer succeeds is showing the passage of time. The movie jumps around on a scale of months, and in southern California, you can’t rely on the weather to do any of the heavy lifting. Ayer was forced to craft convincing backstories for his characters beyond them sitting around and reminiscing about onscreen events that happened ‘months ago.’ In so many films, the personal lives of the cops are either handled poorly or add nothing to the story. Ayer was walking a fine line when he decided to give his cops lives. He stayed away from the clichés, kept it simple, and thus kept it engaging.

There was one aspect of the film that failed miserably. That old spectre, that favorite filmmaking method I love so much, the faux documentary, made an unfortunate appearance. In the hands of a highly skilled filmmaker, it can be used to effect. But in End of Watch, it’s treated as an affect, little more than an excuse for weird camera angles. Worst of all, it’s inconsistent. Every scene in the film jumps between the cameras wielded by characters (with only token reasons given for them), and those wielded by the conventional, unseen crew. A film cannot half-ass faux documentary, cinema verité, or found footage. As soon as traditional camera angles are introduced, it completely negates the point of having the characters be the photographers. All in or all out.

That wasn’t the only flaw with End of Watch, but it was the largest, because it was so damned sloppy. I’m sure many viewers won’t care. There are plenty of other aspects that keep this film merely good, and not great. But from an artistic and a technical aspect, swapping so haphazardly between traditional shooting and characters shooting footage was a very poor decision.

What End of Watch feels like, in the end, is a fine first effort from a new filmmaker, which it is decidedly not. I’m willing to pretend it was made by someone who lacked the experience to craft a better film, but I shouldn’t have to. I like this movie, I really do, but I doubt it’s worth seeing more than once.