So, who really directed Poltergeist? Part of the Hollywood mythos the last few decades treats this as an open question. Was it Tobe Hooper, the man at the top of the credits? Or was it producer Steven Spielberg? It was such a serious concern among the Directors Guild that they launched an investigation into whether or not Spielberg had tried to snatch credit away from Hooper. Honestly, no one involved is saying definitively one way or the other, but Hooper is a competent storyteller with fine directorial vision, and I can’t see him having a film taken away from him. That being said, it’s also hard to picture Spielberg letting a director that was not him have total creative control over a flick he was very much involved in as producer. So did Spielberg direct Poltergeist? Who knows, and who cares?

If Poltergeist can, at best, be described as a collaborative effort between Hooper and Spielberg, that’s fine, because Poltergeist is a hell of a ghost film.

Here at Missile Test, ghost films have supplanted zombie flicks as our favorite type of horror film. More than any other genre of film, ghost flicks consistently bring the scary, for at least the first half of a film. Strange goings on, ghostly shenanigans, etc., are very effective at creating unease in an audience. Right up until the point when the ghosts shift things into overdrive, a ghost film has more inherent fright than a film with slashers or zombies or monsters. Ghosts, for the most part, remain unseen for the balance in most ghost films, and what is unseen or unknown is scarier than anything that has a lot of screen time. In that, the very idea of a ghost is an aide to the filmmaker. Our conception of spirits as an unseen, unstoppable, and unknowable entity that we are  powerless against makes them much more frightening than something concrete, something we can see. If we can see it, we can hide from it. Whereas a ghost...it can make itself known at anytime, with complete unexpectedness.

powerless against makes them much more frightening than something concrete, something we can see. If we can see it, we can hide from it. Whereas a ghost...it can make itself known at anytime, with complete unexpectedness.

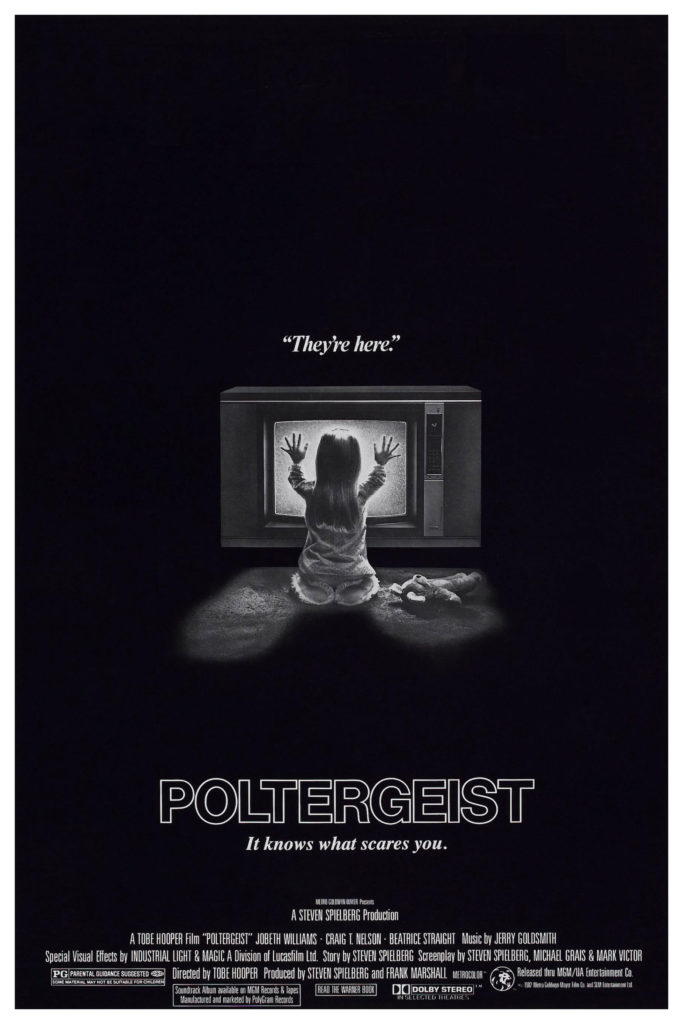

From 1982, Poltergeist is the story of the Freeling family, a five-strong SoCal suburban set that begins to suffer disturbances in their home. It starts out innocently, but creepily, enough. As the film opens, we see the youngest member of the family, five-year-old Carol Anne (Heather O’Rourke), wake in the middle of the night and begin talking to a television showing a screen with nothing but snow. (How much a tale of the times. Snow used to be a regular occurrence on television screens. Now a person has to work a little bit to get their screen to show static.)

From there, Hooper (yes, I’m going with the man given credit for directing) spends the next twenty minutes showing us the ins and outs of a family in suburbia. It was a necessary diversion to develop characters and context. I feel it was unavoidable, but also a testament to his skill as a storyteller that this sequence flies by, and brings the viewer into much closer contact with the Freelings before the ghostly happenings resume.

When they do resume, we find that the ghosts have kidnapped Carol Anne. Why they want her is a mystery. But all that a viewer need know is the Freelings are now consumed with getting her back. Carol Anne is still in the house, crossed over to a spiritual plain. What began as minor disturbances now rule the family’s life, to the extent that they seek help from a university in finding out just what is happening to them.

If this seems familiar, that’s because Poltergeist is the progenitor of a subset of ghost films that follow a now-set formula. A child befriends a ghost, the mother discovers the newly disturbing behavior in their child, the ghosts step up the tricks, the child becomes endangered, psychics and/or university folk are called in, the husband remains skeptical despite all evidence, followed by denouement, usually in the form of a false ending that requires further resolution. These films are released all the time. Just like all zombie flicks pay homage to George Romero, every family in trouble ghost flick owes a debt to Poltergeist. Like many progenitors in film, Poltergeist does the idea best.

Another great thing about Poltergeist is that it fully inhabits its time. I guess it’s pretty easy to make a film in 1982 that looks like it takes place in 1982, but there’s something more going on. The setting feels effortless. The interiors of the Freeling home definitely inhabit a soundstage, but in a strange way, it feels like home. I was five years old when this film was made, and I remember that world. I remember the turntable on the bookshelf. I remember the television of human proportions, the phone on the wall, the lack of personal computers or cell phones. More than that, I can recall that so many films fail to convey in their setting that they take place in a real space, that they are merely mimicking the real. It has nothing to do with the story, but Poltergeist works very well as a contemporary snapshot of the times in which it took place. Bravo to James H. Spencer for production design and Cheryal Kearney for set decoration.

The cast displays a similar effortless realism. JoBeth Williams and Craig T. Nelson as Diane and Steven Freeling weren’t angling for any Oscars, but they meld well into the overall naturalism of the film. Even the kids, normally the weak spots in any film in which children are featured prominently, pull their weight. No one in this flick feels like they’re acting. Only Beatrice Straight, as the psychologist Dr. Lesh, brings Hollywood expectations to her performance, and even she was good. If there was a weak spot in the performances, it resides with the diminutive Zelda Rubenstein, who plays the psychic Tangina Robbins, but her character was so eccentric that it’s easy to forgive her lack of experience as an actor. All around, Hooper brought out the best in the cast, making sure a viewer sees the characters and not the actors.

The film also suffers none of the vagaries of typical ghost flicks. Usually, as a ghost flick carries on, the ghostly activities continue to ratchet up to the point the viewer becomes inured to the actions on the screen. We become accustomed. Not here. While the scary does eventually taper off, a bit, the plight of the family and a viewer’s desire for resolution keep things tight throughout. This is how to make a proper ghost film.