I’ve seen hundreds of horror films. And I’ve seen more Dracula films than I can either count or name. But until recently, I had no idea that this version of the oft-filmed tale existed. This Dracula is so lost to the digital history of cinema that when I searched for it on IMDb, I had trouble locating its page. I have a hard time understanding why.

I’ve seen hundreds of horror films. And I’ve seen more Dracula films than I can either count or name. But until recently, I had no idea that this version of the oft-filmed tale existed. This Dracula is so lost to the digital history of cinema that when I searched for it on IMDb, I had trouble locating its page. I have a hard time understanding why.

Perhaps Dracula has been adapted for the silver screen so many times that there is a sense of fatigue surrounding the character. Certainly, once a viewer latches on to a particular film as their favorite, only a morbid fascination with the character would compel one to dig through the continuously growing pile of Dracula films looking for a hidden gem. But that’s precisely what this Dracula is.

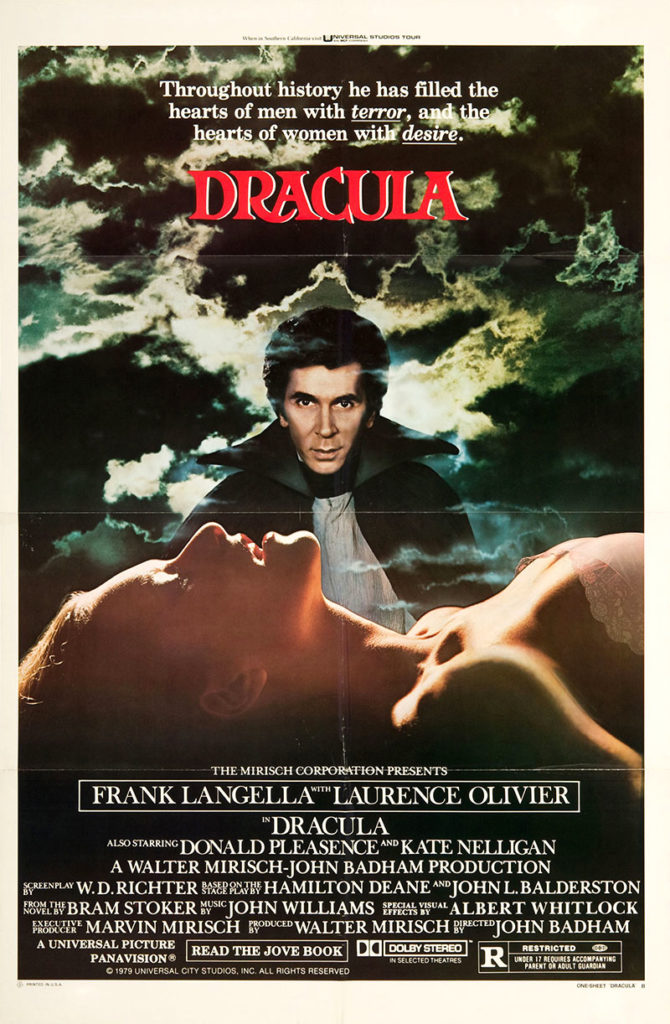

From 1979, this Dracula is an adaptation of both Bram Stoker’s novel and a stage play that ran on Broadway. Reprising his role from the play is Frank Langella as Dracula — a tall, rugged charmer with a gigantic mane of David Copperfield hair. Alas, the 1970s. Director John Badham helmed a film that is quite a compression of the novel, but it’s also very lean. I can only guess that this leanness is a result of the film using a stage play as part of its source material. The necessities of film and stage require that a story with the scope and breadth of a novel has to be trimmed down to fit very real budgetary and physical constraints. The play, being a successful production, probably got the bulk of that work out of the way, leaving the film free to breathe back out a bit on what the play sucked inwards.

By this, I mean no play, ever, has had sets quite like what a viewer will find in Dracula. Designed by Edward Gorey, of all the Dracula films I’ve seen, this is the most visually striking. The sets are morbidly creepy, and cinematographer Gilbert Taylor chose to mute the colors to the point that the film is one step above black and white. Imagine the most depressed, overcast day in the dead of winter one has ever seen, a dreadful day capable of casting a person into a very melancholy mood, and it’s like a holiday in the tropics compared to the world the characters of this film inhabit.

Dracula comes into that world very quickly in this film. It was a dark and stormy night, and a ship carrying the Count in a pine box runs aground, spilling its evil occupant onto the shore. He’s found and supposedly rescued by the lovely Mina Van Helsing (Jan Francis). Later she becomes his first victim, and the story is set into full motion. Any viewer familiar with the material will recognize the same cast of characters, with a whole bunch of poetic license thrown in for expediency, beginning with Mina. There’s the lawyer Jonathan Harker (Trevor Eve), his fiancée Lucy Seward (Kate Nelligan), her father Jack (Donald Pleasence), and, of course, Professor Van Helsing (Laurence Olivier), who is also Mina’s father in this version.

After some initial doubts, it becomes clear that Mina has fallen prey to a vampire, and suspicions fall rightfully on Count Dracula. The remainder of the film showcases the struggles of the main cast in hunting down and killing the beast. We all know how this ends beforehand, so the only question is, how was the execution?

Like most versions of Dracula, there’s a plodding sensibility to the pace, and this film is no exception. But it’s never boring. We’ve been desensitized by high body counts and endless gore in modern horror. This story is older than all that, from a different era of storytelling, and it follows rules from then, rather than what we’re used to. Most of the characters are richly realized and played well, even down to the character of Renfield (Tony Haygarth), who is reduced to an unnecessary also-ran in this production.

Dracula may be firmly entrenched in the late nineteenth century, but it is a timeless story nonetheless. There will always be filmed adaptations for as long as people continue to make movies. This is one of the best ones.