Oh, no. Not another found footage horror flick featuring amateur filmmakers traipsing around the woods. A big part of me, bigger than I would like to admit, wishes that filmmakers would just stop with this nonsense. Found footage is a grossly overdone gimmick in horror films. Consequently, the bar for success has been raised so high that only the most talented of filmmakers can hope to produce a film that adds anything to this tired method of storytelling. So, sorry in advance, Bobcat, but I did not go into your film with the highest expectations.

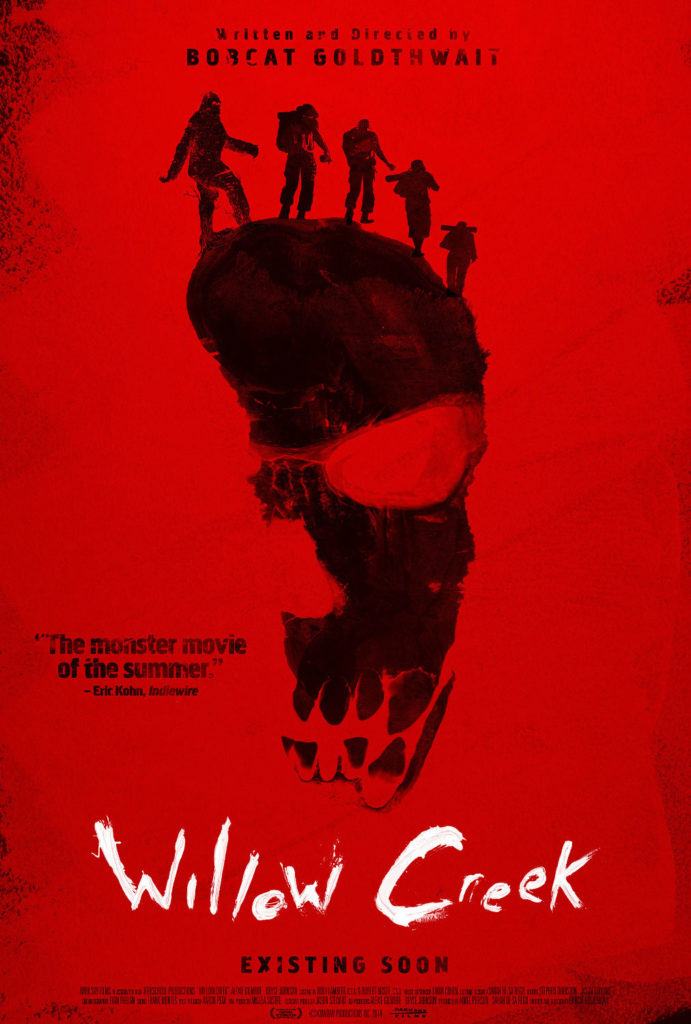

Willow Creek was written and directed by Bobcat Goldthwait. Bobcat has been in the entertainment business for over thirty years. In that time he has been a successful and groundbreaking standup comic, a sellout joke who clowned around in a few Police Academy flicks, and a behind the scenes mover, building a solid career of work from the other side of the camera. Bobcat is one of those celebrities we seem to be perennially surprised by when we learn that he didn’t crawl into a dark hole when the peak of his celebrity passed. He’s a worker, and he’s always had talent. So, while the prospect of reviewing another found footage horror flick made me shake my head, I was intrigued by what Bobcat might have come up with.

Willow Creek takes place in and around the eponymous town in Humboldt County, California. Maybe a couple of the Loyal Seven are familiar with the town, as the real life location bills itself as the Bigfoot capital of the world. The most famous footage of the cryptozoological creature, the Patterson-Gimlin film, was captured in nearby Bluff Creek. Anyone who has had a passing interest in the coolly bizarre when they were children has seen this film, even if they have never heard of Willow Creek. It begins with the camera shaking violently up and down. There is no sound, and the color is very washed out, like the photos in old picture albums from the 1950s and ’60s. Finally whoever is shooting the  film manages to steady the camera, and a viewer sees a lumbering black figure, tall and thick, walking past some felled trees on the rocky shore of a creek. It turns its head back towards the camera, but only for a moment, and continues on its way.

film manages to steady the camera, and a viewer sees a lumbering black figure, tall and thick, walking past some felled trees on the rocky shore of a creek. It turns its head back towards the camera, but only for a moment, and continues on its way.

It seems like whole libraries have been written analyzing this short bit of footage, lasting less than two minutes. It’s been called everything from a hoax to definitive proof of the existence of the Sasquatch. I watched the film again after finishing Willow Creek. As for what I believe...well, this is the October Horrorshow. How can I delve into the grim, the frightening, and the mysterious for an entire month and not keep an open mind? Once the heady hangover of dozens of horror flicks has passed by, and the holidays are fast approaching, maybe then, and only then, will my eye become too critical, too rational. For now, I did not see a man dressed in a cheap costume store gorilla suit in the grainy footage. I saw no hoax. No, I saw a missing link, a creature spoken of in legends crossing multiple cultures throughout multiple eras. And it was walking amongst us.

It is the Patterson-Gimlin film that brings Willow Creek’s two protagonists to town. They are aspiring viral filmmaker Jim (Bryce Johnson), and his girlfriend, aspiring actress Kelly (Alexie Gilmore). Jim has been into Bigfoot since he was a child. He never managed to let go of the legend as he aged, unlike Kelly. She is an unbeliever, but she agrees to accompany Jim up into the forest on his snipe hunt because she is an awesome girlfriend.

Half of the film’s short run time (a weary reviewer-friendly 79 minutes) is spent in town providing the viewer with background on Bigfoot. Much of this footage features Willow Creek locals as themselves, as Bigfoot is big business in the area. Eventually, the two heroes set off for the woods, and are warned more than once by some hostile locals to go home. But, there would be no movie if they gave in to intimidations and threats, so onwards they go.

When Jim and Kelly make their way into the wilderness, the film takes quite a turn. Rather than being just another entry in the found footage subgenre of horror, it becomes a full-on Blair Witch clone. From the lonely isolation of a tent at night, to the sounds out in the woods, Blair Witch informs the progression of Willow Creek more than any other film I can think of. I can’t tell if its homage, lack of originality, or outright copying. The weird thing is, I hated Blair Witch. I thought spending an hour and a half with three Gen X-ers in the woods while unseen people run around in the dark making noises was interminable, both when I saw it in 1999 and this year. Yet, there I was, spending another night in a tent, this time with only a pair of Gen X-ers, while some production crew were outside making noises, and I did not hate it. In fact, the long sequence in the tent, consisting of a single take, was very well done. I didn’t find it all that frightening, but it was a tight sequence that required perfect timing on the part of the crew and the director, and imagination from the actors, who clearly were required to improvise much of their dialogue. It’s the degree of difficulty, not its originality, that makes this scene so satisfying.

Despite any aspersions I cast on my generation, I like Bobcat’s decision to cast a couple of my contemporaries as his leads. Horror is a young person’s market. Every production company understands that. That is why so many horror flicks feature young people. Teenagers and the newly adult have blinders on and they don’t even know it. Those outside their age group are mostly invisible — there, but not there. Any director that decides against casting someone who is in their early twenties in their horror flick is taking a chance. Ridley Scott did it, wanting his characters to be a future equivalent of modern blue-collar workers. The result was Alien, a masterpiece. Willow Creek is no masterpiece, but casting Johnson and Gilmore was inspired. Their age and experience makes what they do on screen believable before they even utter a line. I’m sure Bobcat knows how much trouble he saved himself by hiring them. In fact, the only thing that hampers their performances is the predictable nature of the movie itself.

I would say that is Bobcat’s fault, but that would make it seem as if I thought Willow Creek is a bad film. It is not. It’s a good movie — a fine example of found footage horror. But by this point it’s just about become an anachronism. Had this film come out in 1999, instead of Blair Witch, many people would be hailing Bobcat as a horror visionary. What he showed here is that, like so many in Hollywood have learned before about him, he is a competent, professional entertainer. He may never find his Shangri-La in the business, but his days of begging for change are long gone.