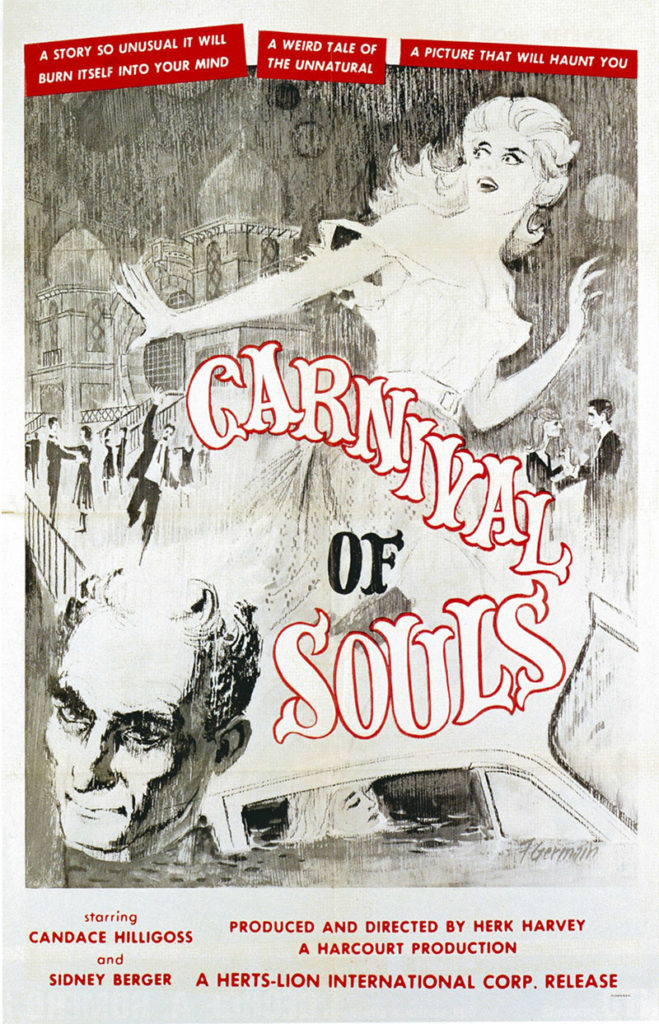

Who the hell is Herk Harvey and what is Carnival of Souls? Well, Herk Harvey was a filmmaker from Kansas whose directing career spanned three decades encompassing no less than 46 titles. His IMDb page lists such titles as What About Juvenile Delinquency? and Exchanging Greetings and Introductions. It’s not typical Hollywood fare. The vast majority of Harvey’s work consists of short educational films for schools and businesses. A few can be found online for the curious, and they’re just what one would expect. The sole feature film in Harvey’s career is Carnival of Souls, which he directed and wrote (with John Clifford) in 1962.

Carnival of Souls is a low-budget film that Harvey shot in a few weeks using his vacation time from employer Centron Corporation. It’s a burst of unrestrained artistic creativity from a talent who otherwise would have remained in obscurity. Oh, let’s be honest. Carnival of Souls is still obscure, and were it not in the public domain, would probably be more so. I’m just glad that Harvey found a way to get this film made, and that I have been fortunate enough to see it.

The film starts off showing its educational film heritage, with a car full of teenage boys challenging a car full of girls to a drag race, with tragic results for the girls. The way this scene is constructed is identical to the types of safety films many of us were forced to sit through during our youths. But it also has much in common with avant-garde cinema. I’m not joking. There are some clumsy bits in this opening sequence, but it’s pretty clear early on that there’s something special going on with this film.

There were three young ladies in the  car during the race, but only one of them survived. She is Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss), a professional musician who is spending her last days in Kansas before leaving for Salt Lake City to take a position as an organist in a church. Mary seems unconcerned with both the accident and the spiritual nature of her profession, much to the consternation of those around her. In many ways, she seems to float through existence — part of the world, yet not of it.

car during the race, but only one of them survived. She is Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss), a professional musician who is spending her last days in Kansas before leaving for Salt Lake City to take a position as an organist in a church. Mary seems unconcerned with both the accident and the spiritual nature of her profession, much to the consternation of those around her. In many ways, she seems to float through existence — part of the world, yet not of it.

The sublime weirdness of this film begins after the car accident, when Mary sits down at a colossal pipe organ and begins playing. The organ music, which permeates most of the film, was performed by Gene Moore. The music provides just as much atmosphere to Carnival of Souls as does Harvey’s direction and cinematographer Maurice Prather’s high contrast black and white photography.

The organ music is a constant companion to Mary in both the sunny moments in her life and when she sees visions of a pale-faced man (Harvey himself) stalking her.

Mary is never sure if what she is seeing is real, but she really begins to come unhinged in moments when the world around her goes completely silent and she seems to exist out of phase with reality. No one can see her or hear her. It’s a horrifying condition in which to be, and leaves Mary understandably rattled after things return to relative normality.

Mary latches on to an abandoned building on the shore of the Great Salt Lake (the Saltair pavilion which, in its second incarnation, was abandoned at the time of filming). The building threatens to throw the film into fun house trickery, not necessarily a bad thing in other films, but Harvey pulls back just in time. Mary’s hallucinatory visions and fixation on the abandoned pavilion continue to grow, until a final danse macabre at the pavilion that lends credence to the film’s title.

Carnival of Souls isn’t the type of film that spends a lot of time trying to confuse the viewer, but it is a mind-fuck. Mary has no idea why she is plagued by such disturbing visions as the pale-faced man, and Harvey provides no clues until the end. Denouement consists of no great twist, something which modern audiences have come to expect, but it can be guessed at, despite Harvey doing all he can to not telegraph the ending.

There is much about this film that is far from perfect. Only Hilligoss appears to have been trained in acting, much of the cast having this film as their only credit or being part of Harvey’s work at Centron, and even she can be wooden at times. The film rests squarely on Hilligoss’s shoulders. When she is frantic and consumed by fear, she is more than capable. But when tasked with reading lines, her limitations begin to show.

None of that seems to matter. Yes, Carnival of Souls is low-budget horror, but it is far from the dime-a-dozen fare one would normally expect from the genre. This film is a work of art.