I couldn’t say how many times I’ve seen Jaws. It’s been so many times that the film feels like a familiar presence in my life. My first viewing was so long ago that it’s mostly faded back into the ether, consisting of little snippets that have been distorted by time. I remember that I was young, maybe five or six years old, and that my old man was there to make sure I covered my eyes during the gory bits. Was it irresponsible to let someone so young watch a movie featuring such gruesome scenes of death as Jaws? Well, it was rated PG, for Parental Guidance, and that’s just what I got. I was too young for the gore, but there were about 120 minutes of really good movie that wouldn’t cause nightmares, and that I got to see until I was old enough for the rest.

My point is, I’ve seen Jaws a lot. It shared a well-worn VHS tape with Logan’s Run, making a more compatible double bill than one would expect. I can quote the movie forwards and backwards, even though I’m decades away from the time when I would watch it 3-4 times a year. I watched it again for this review, and it had probably been a few years since I last saw it, and there were no misremembered scenes or discrepancies. By this point in my life, the entire flick is nostalgia, which means this is hardly an objective review. But, so what? What am I going to do? Write a review where I don’t argue that Jaws is one of the best movies ever made? That wasn’t going to happen, even if I had not already been familiar with the film.

Jaws is one of those scary films that I, and many others, have seen so many times that the frightening bits have lost their effect. That might be one of the reasons Jaws doesn’t come to mind when thinking of horror flicks. Jaws is regarded as a classic and groundbreaking movie, period, and genre doesn’t seem to matter. But Jaws is a  horror film. I would challenge a reader to think back to the first time they saw Jaws, and remember Ben Gardner making his sudden and unexpected appearance. Or the scene with the poor fellow in the rowboat. Those scenes, and more, were as frightening and unsettling as anything involving ghosts or zombies.

horror film. I would challenge a reader to think back to the first time they saw Jaws, and remember Ben Gardner making his sudden and unexpected appearance. Or the scene with the poor fellow in the rowboat. Those scenes, and more, were as frightening and unsettling as anything involving ghosts or zombies.

For those rare people who haven’t seen it already, Jaws tells the story of a man-eating shark terrorizing the fictional community of Amity Island (Martha’s Vineyard). The shark is a beast, bigger than the film’s resident shark experts have ever seen, but this isn’t some giant monster flick. The villain in this movie is plausible, although its behavior in the final act is a little too close to human than animal.

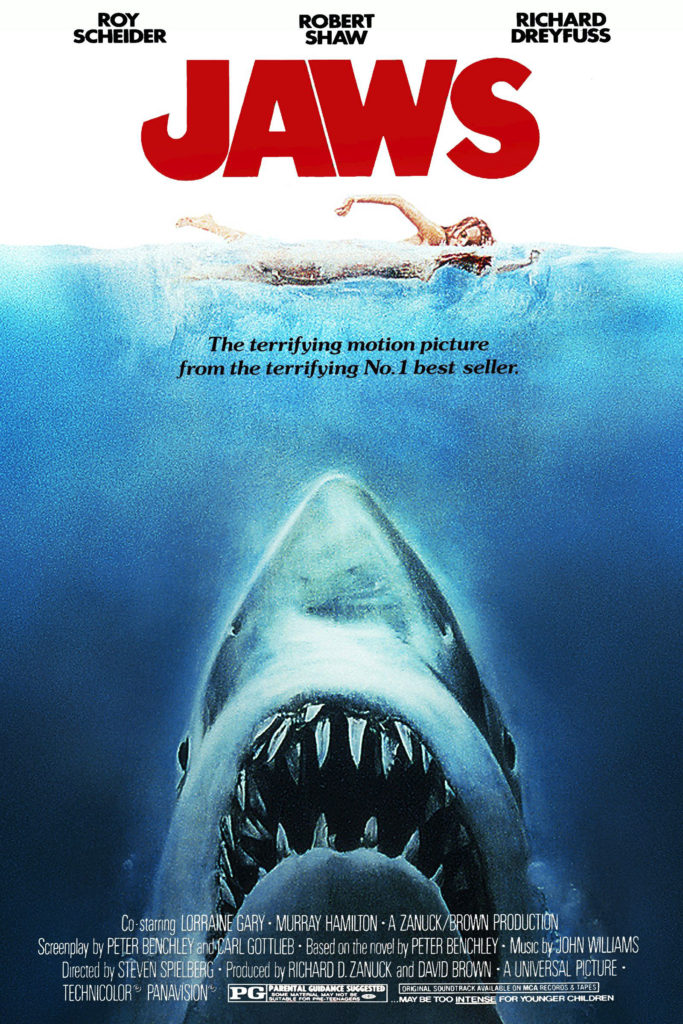

The responsibility for the safety of the town rests on the shoulders of Sherriff Martin Brody (Roy Scheider), a recently retired NYPD officer who thought he was headed for a cushy sunset to his days in law enforcement, and instead finds himself with a growing pile of mangled corpses. Worse yet, the summer season is about to start, and if word gets around that the waters around the island aren’t safe, then the island’s economy will crater.

There are all sorts of nits to pick when it comes to the behavior of the civic leaders in this film, and Brody’s initial overreaction to a single fatality, but the first act does a wonderful job of setting up the film. Steven Spielberg, directing his second feature film, was already a master at storytelling. There’s no wasted space anywhere in the buildup to the final act. Characters flit about in their own orbits, each reacting to the shark attacks in sometimes selfish, contradictory fashion. There’s almost a feeling of denial among the populace, as if they’re drifting and unable to comprehend what is happening. But enough eventually becomes enough and a plan is formed to hunt down the killer shark, leading to an incredible final act out on the ocean — a sequence ruled over by Robert Shaw’s tyrannical performance as Quint.

Shaw had barely been in the movie up until the Orca sets sail, but his dominance of the final act ranks up there with Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now or Max von Sydow in The Exorcist.

The tension and suspense in this film are so well done that it comes as a surprise that it’s just as much the result of production troubles as masterful storytelling. Spielberg wanted the shark to be in the film much more than it was, but the mechanical stand-in was mostly a worthless piece of junk. Because Spielberg and his crew couldn’t get the thing to work most of the time, there are only brief moments when the shark appears on screen. Spielberg discovered, by accident, the true secret to tension in horror films — that which is not seen, but alluded to, is far more frightening than that which is seen. The shark becomes a constant menace even when it’s not around. Characters and viewers can see miles of water, but the grey-green sheen of the Atlantic Ocean might as well be a black shroud, perhaps hiding the shark just below. One can never see it coming, and that, as much as the shark’s deadly nature, is what makes Jaws a very scary movie.