Before The Hunger Games, there was Battle Royale. In fact, it’s not all that hard to go back through literary and film history to find stories about groups of people being hunted in a confined environment, commonly an island. Some pit characters against each other, while some feature characters whom are hunters, specifically. A quick trip through my memory (aided by the Google machine) brings up The Most Dangerous Game, The Running Man, and even Death Race 2000. This isn’t a hard idea to come up with, which is why Suzanne Collins, the author of The Hunger Games novels, can plausibly claim that she never heard of the book and film Battle Royale before the similarities were pointed out to her.

So, the idea of pitting people against each other in a fight to the death is easy, but it is totally unbelievable. These stories are all about state control over its citizens. It always seems to be the government that conducts these games for the entertainment and pacification of the masses. But no story involving this type of state-sanctioned violence has ever adequately explained how it calms the masses. And there is no comparison to Roman gladiators. I’m referring to modern moralities and sensibilities. Not the Soviets, or the Chinese communists, or the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, or the Kims in North Korea, or the Pinochet regime in Chile, nor the Nazis, all at their most oppressive, ever staged blood sports like that featured in Battle Royale. That’s because there are many more direct ways to control a populace than a violent reality show. Disappearances and mass graves have been proven to be effective.

That makes something like Battle Royale pure fantasy — an exercise in wouldn’t-it-be-cool-if-ism. A lot of story ideas begin like this. “Wouldn’t it be cool if terrorists seized a skyscraper?” brought us Die Hard. “Wouldn’t it be cool if a giant alien spaceship blew up the White House?” brought us Independence Day. Et cetera, et cetera,  et cetera. Even this reviewer isn’t immune, once asking himself, “Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a apocalyptic asteroid impact and the government hid itself away in a gigantic bunker?” And that’s how I wrote my first novel.

et cetera. Even this reviewer isn’t immune, once asking himself, “Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a apocalyptic asteroid impact and the government hid itself away in a gigantic bunker?” And that’s how I wrote my first novel.

Back in the 1990s, a young Japanese journalist named Koushun Takami asked himself, “Wouldn’t it be cool if a junior high school class was forced to hunt each other to the death on a deserted island?” The answer is ‘yes.’ It would be cool. The result was Takami’s only novel, titled Battle Royale. It was a big hit, adapted into both manga and film.

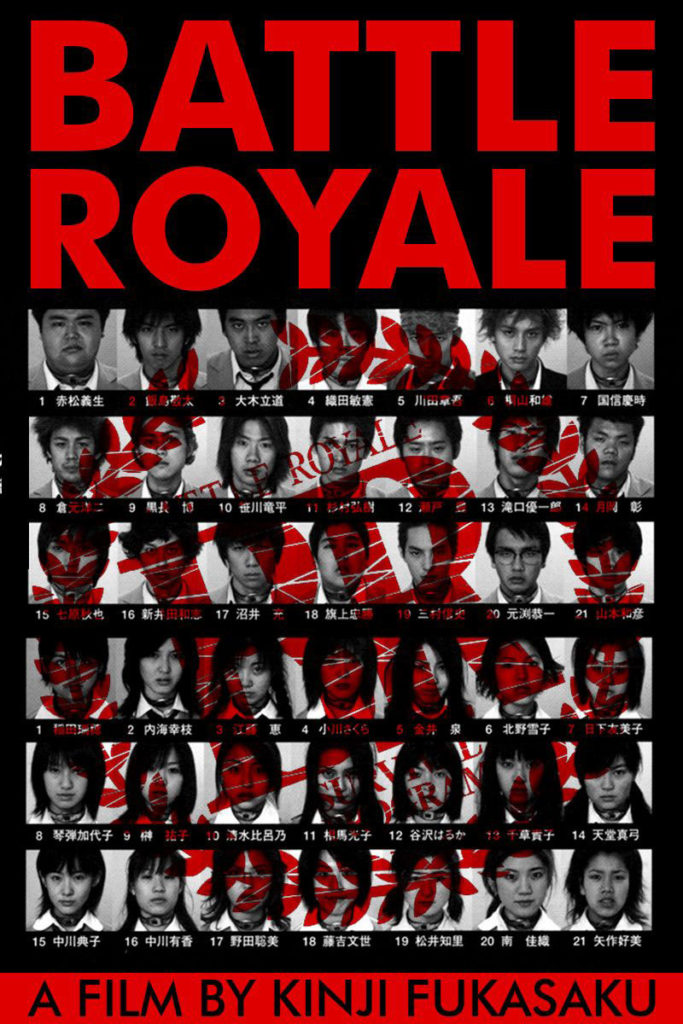

The film adaptation, from 2000, was directed by Kinji Fukasaku, from a screenplay by Kenta Fukasaku. It stars a large ensemble cast as the junior high students. The most prominent cast members are Tatsuya Fujiwara as Shuya Nanhara, Aki Maeda as Noriko Nakagawa, Taro Yamamoto as Shogo Kawada, and Masanobu Ando as Kazuo Kiriyama. Famed filmmaker and actor Takeshi Kitano also has a prominent role as the class’s former teacher turned game master, supervising the class as they are taken from school to the deserted island mentioned above, and set loose on each other. For three days, the students will hunt each other to the death until there is only one left.

The kids aren’t just turned out in a free-for-all, of course. There are rules to be followed. Each student is given a backpack of supplies and a unique weapon, and a chance to flee into the wilderness before things jump off. Their participation in the game is compelled by an explosive collar around their necks that can be triggered remotely. Certain areas of the island are off limits. Should a student enter an off limits area, the collar will blow, severing the arteries of the neck. More off limits areas are added to the island at regular intervals, forcing the students to move about and funneling them into a smaller area as the game goes on. Should there be no winner after three days, all surviving students’ collars will explode. That’s some good, bloody fun.

The whole idea behind this film is absolutely absurd. Thankfully for the audience, Fukusaku knew that. Despite the dire circumstances of the students, things never get too heavy. The acting from the young performers is intentionally over the top, as is the violence. Kitano also seemed to revel in the silliness of the whole enterprise, embracing the black humor and, at times, outshining the contest out on the island.

Being very aware of the material he was working with, Fukusaku took Paul Verhoeven and Stanley Kubrick as his influences, especially when it came to the film’s cynicism, but also in its atmosphere. It approaches pale imitation at times, but if that were really a problem, then The Hunger Games would have slunk into a corner and apologized profusely for its bright, shining thievery. The absurdity might also be Fukusaku’s contribution, as I read Takami’s book many years ago and don’t recall any similar self-awareness.

For just about two hours, viewers are treated to a couple dozen bloody teenaged deaths, and it’s glorious. I never would have expected something this violent to be so funny. The film has flaws in abundance, starting with some terrible CGI effects, but just about all the flaws are overcome by its rollicking nature. There’s some deeper stuff going on should a viewer be willing to think on things, but why? For me, I was content watching Japanese school kids — just about the least threatening juveniles on the planet — murder each other.