Hammer saw much success with its version of Dracula in 1958. Of course they wanted to cash in further. For reasons beyond the scope of this review, they couldn’t nail down Christopher Lee for a sequel until 1965. But that didn’t stop Hammer. In 1960 they released The Brides of Dracula, which featured neither Dracula nor any vampire that appeared with him in the previous film. It was misrepresentation, plain and simple. In watching it, it becomes clear Brides was meant to be a Dracula film, with Lee in it, but the script had been reworked to put a different baddie in the lead. The Kiss of the Vampire has similar origins, although with this film Hammer had the decency to release it without a false pedigree.

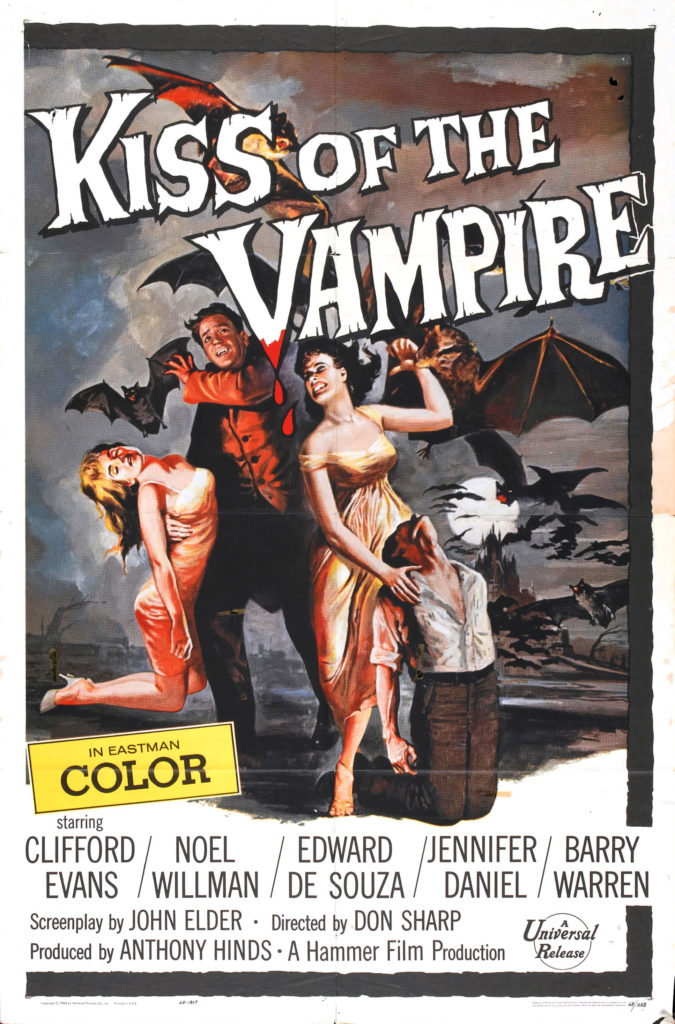

From 1963, The Kiss of the Vampire tells the tale of English newlyweds on their honeymoon who become the target of a vampire cult.

While traveling on the continent, Gerald and Marianne Harcourt (Edward de Souza and Jennifer Daniel) find themselves lost and stranded after their puttering, turn of the 20th century automobile runs out of gas. This being the early days of autos, there’s nary a filling station to be found. But that’s okay, because the car quit on the Harcourts within sight of a creepy castle on a mountaintop. This is the home of Dr. Ravna (Noel Willman), the head of a vampire cult that is always on the lookout for new members.

Viewers familiar with Hammer’s Dracula films will see that this film sets itself up just like one of those. Unwary travelers find themselves in Dracula’s homeland and wind up being targeted for Dracula’s dinner. Cross out Dracula’s name in the script and  replace it with Dr. Ravna, and one gets The Kiss of the Vampire. But that’s not all screenwriter Anthony Hinds (using his nom de plume, John Elder) did to change things around.

replace it with Dr. Ravna, and one gets The Kiss of the Vampire. But that’s not all screenwriter Anthony Hinds (using his nom de plume, John Elder) did to change things around.

It’s not all that clear that the vampires who inhabit this film, and there are more than just Dr. Ravna, are really vampires at all. They could just be deluded cult members who are acting out twisted rituals, or they may actually believe they are vampires. Many of the rules regarding vampires are only casually followed by these cultists. Sunlight doesn’t kill them, but when they see the sun they run for shelter. They sleep in coffins but it’s never shown if that behavior is something vital to them, like it is to Dracula, or if they’re doing it because they’re supposed to. Even their vampire teeth could just be porcelain veneers.

Ravna never presents himself as the menacing figure of the undead that one would expect. There is nothing of the demon and everything new age SoCal cult leader about him. His people worship him. His word is sacred and must be obeyed. He gets top choice of every female who comes under the influence of the cult. He decides when and on whom his disciples feed. He controls every aspect of the cultists’ lives, insisting they all live in his gigantic home and wear flowing white robes. Dr. Ravna puts a mark next to every item on the cult leader checklist.

But there are supernatural elements to the cultists and Ravna that are enough for most viewers to assume that these characters are the undead. Not enough for me, though. If it was Hinds’ intention to confuse the matter, then mission accomplished. If not, then it was a happy accident that gave what could have been a rote Hammer flick some much-needed individuality and depth. Of course, I could be completely wrong. I’ve read other reviews and synopses of this film and there is no mention of the ambiguous nature of the vampires. I’ve seen this flick twice now, and I can’t tell one way or the other. Personally, I prefer the idea that the cultists are over-enthusiastic cosplayers, but the evidence does point to them being actual vampires.

This peripheral stuff overpowers the plot. That’s easy to do considering how similar it is to other Hammer films. The story just sort of floats along, never challenging or straying too far into the unfamiliar. There’s a Hitchcockian element introduced at one point that perks things up in the middle, but it was then abandoned so swiftly I have to wonder why it was included at all.

Director Don Sharp, while working with similar material, doesn’t measure up to Hammer stalwart Terence Fisher. There’s a little too much of the stage play to this film. It doesn’t break the bounds of its sets and its lighting — doesn’t take the viewer away to someplace new. Suspension of disbelief is shattered at many moments throughout, the result of filmmaking that wasn’t as detailed as it should have been. So while The Kiss of the Vampire is very interesting for a Hammer film, the production was harmed by its somewhat lackadaisical and recycled nature.