Back before the great wave of gentrification began to hit American cities in the mid-1990s, there was the 1980s, an era when the distressed environment of the cities bottomed out. Long decades of neglect, strained local budgets, and rising crime left our cities veritable war zones. The inner cities were voids of hopelessness, abject poverty, and filth. Even affluent neighborhoods were just dangerous enough to breed well-heeled residents with canny street smarts, always looking over their shoulders for the dark figure hiding behind a tree or in an alley. This kind of palpable fear of urban environments is contagious, and it entered into our lore. We could envision no bright future for the American city because we had seen decay extend its grip for so long. Today’s cities have not fully recovered, and they remain always on the brink, ready to slide back as soon as people’s cares turn elsewhere, but it’s hard to picture just how bad things got unless one were a witness.

Back before the great wave of gentrification began to hit American cities in the mid-1990s, there was the 1980s, an era when the distressed environment of the cities bottomed out. Long decades of neglect, strained local budgets, and rising crime left our cities veritable war zones. The inner cities were voids of hopelessness, abject poverty, and filth. Even affluent neighborhoods were just dangerous enough to breed well-heeled residents with canny street smarts, always looking over their shoulders for the dark figure hiding behind a tree or in an alley. This kind of palpable fear of urban environments is contagious, and it entered into our lore. We could envision no bright future for the American city because we had seen decay extend its grip for so long. Today’s cities have not fully recovered, and they remain always on the brink, ready to slide back as soon as people’s cares turn elsewhere, but it’s hard to picture just how bad things got unless one were a witness.

There are a few films here and there where our urban legacy is on full display. Wolfen had major scenes, some visually stunning, filmed among the devastation of the South Bronx. The classic film The French Connection was a study in browns — rust and dirt every bit as important a character as Popeye Doyle. Fort Apache, The Bronx was a caricature of the inner city, sometimes offensive, but it came from somewhere real. The Warriors has attained mythical status as New York’s ultimate cult film of the night, playing on our fears of a city gone out of control, at the mercy of costumed thugs. At times laughable, the film still wallowed in very real grit, a symptom of the disease that had befallen the city.

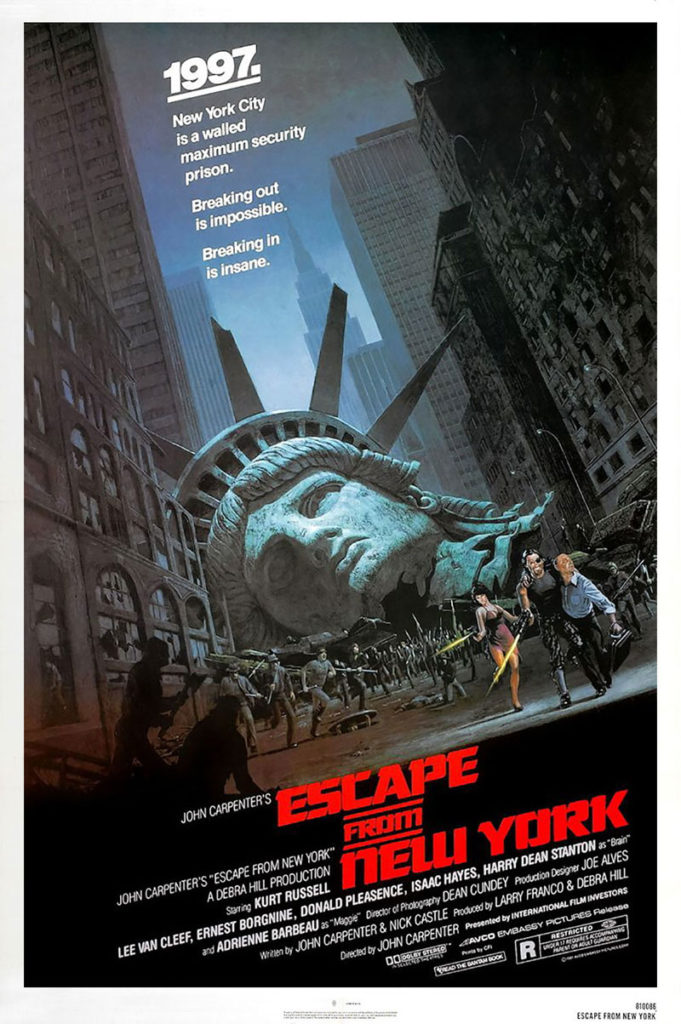

What did we have to look forward to? The cities were a mess and the industrial Midwest was junk. John Carpenter’s vision of the final descent of America into police state fit right in with the descending curve that any fool could see we were in. It was all spiraling out of control, and we still had crack to look forward to. It was strange how reasonable the idea of Manhattan island as a gigantic prison of the future seemed in 1982, and how utterly absurd it is today.

In Escape from New York, Carpenter builds on material he first developed a few years earlier with Assault on Precinct 13, about a partially abandoned police precinct coming under siege by unending waves of murderous, inner city gangs in Los Angeles. Siege is a common theme in many of his films (along with a signature distrust of authority), but these two films deal closest with both the reality and the fantasy of urban decay. In both, Carpenter shows the death of law and order, on a small scale in Assault, and on as grand a scale as could be imagined on a seven million dollar budget in Escape.

Once again, I was able to watch this film on the big screen at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, part of a mini-retrospective of four John Carpenter films. The print was in even worse condition than the screening of The Thing. Whole seconds at the end of reels were excised, the pops and crackles, scratches and lines on the film were heavier, and rich blacks, so important in a film that takes place almost entirely at night, had faded into a deep, muddy maroon. But the audience was raucous, celebrating a film expansive in its idea, if not in its execution. Escape is a bizarre classic, one where viewer can forgive the foibles and flaws, really let go, and just enjoy the senselessness of it all.

It’s the future — 1997. Kurt Russell plays Snake Plissken (that’s right), a former special forces soldier and convicted criminal, on his way to serving a sentence of life on the prison of Manhattan Island. A place with no guards, no rules, and no escape. When Air Force One crashes on the island, the president (Donald Pleasence) survives and is held hostage by the Duke of New York, played by Isaac Hayes. Plissken is offered a deal by the Commissioner of the United States Police Force (Lee Van Cleef!): find and rescue the president within twenty-four hours, and receive a full pardon. After landing a glider on the top of the World Trade Center, Plissken hooks up with a motley band of allies, consisting of a former accomplice (Harry Dean Stanton), his concubine (Adrienne Barbeau), and a New York City cab driver (Ernest Borgnine). From there, the adventure to rescue the president is on. I am not making any of this up. The amount of cliché in that short synopsis could cause whiplash, but this is no b-movie. Low budget, yes. Sometimes stilted performances and directing, yes. Plot holes you could drive a bus through, yes. Yet, it can only be seen to be believed.

Carpenter creates a claustrophobic atmosphere of chaos and decay in his New York (East St. Louis does a fine job standing in for the Big Apple of the future). The extras are all savages and cannibals, what cars drive the streets are dented and pockmarked wrecks, everything and everywhere looks like the underside of a bridge, but in a sign that you can’t keep city hall down forever, the streetlights all work. Anamorphic lenses give the film a distinctive Carpenter look, as does the familiar font in the opening credits over the Carpenter-composed score. In short, we have a typical signature effort from John Carpenter, one where an outlandish concept, hard work, and short funds come together to make an enjoyable film. Carpenter seems to recognize the absurdity of the plot, and strikes a nice balance between playing things straight and keeping it light. It’s a dark film, but celebrates more than wallows in the muck that future society has fallen into. Escape won’t make anyone’s list of the greatest films of all time, but that’s okay.