Last week saw a unique event in film. Four John Carpenter films landed in Brooklyn as part of a mini-retrospective at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM). The featured films were Big Trouble in Little China, The Thing, They Live, and Escape from New York. All unique films from a unique filmmaker. B-movie schlock artist or perennially misunderstood genius, depending upon who’s doing the watching, Carpenter is a knowledgeable director who draws on his education, talents, and the best aspects of low-grade cinema to craft films that are unmistakably his. As soon as the opening credits roll, one enters Carpenter’s world. Viewer hears music (usually) from Carpenter’s own synthesizer, and the credits themselves are all the same white serif font on a black background, no matter which of his films is playing. Anamorphic lens effects and dark lighting cross among his works. Finally there is the thematic distrust of authority as a conceptual continuity throughout. All of this makes Carpenter’s films easily recognizable to anyone with even a cursory knowledge of his oeuvre.

I attended two of the screenings, for The Thing and Escape from New York, although I am familiar with all four films. For this article, I will write about The Thing.

John Carpenter is a guilty pleasure on my part. I fall strictly in the middle among his fans and detractors. The man knows how to make a movie, but I have no illusions about him being one of the giants of the art. However, he is too proficient to be considered kin to monster movie directors like Bert I. Gordon or assembly line bottom feeders like Michael Bay. Carpenter knows what he can do, and often, was only able to work with what he had. Keeping that in mind, he worked some minor miracles on the silver screen, and had one giant smash hit, Halloween, that created the slasher genre of horror films.

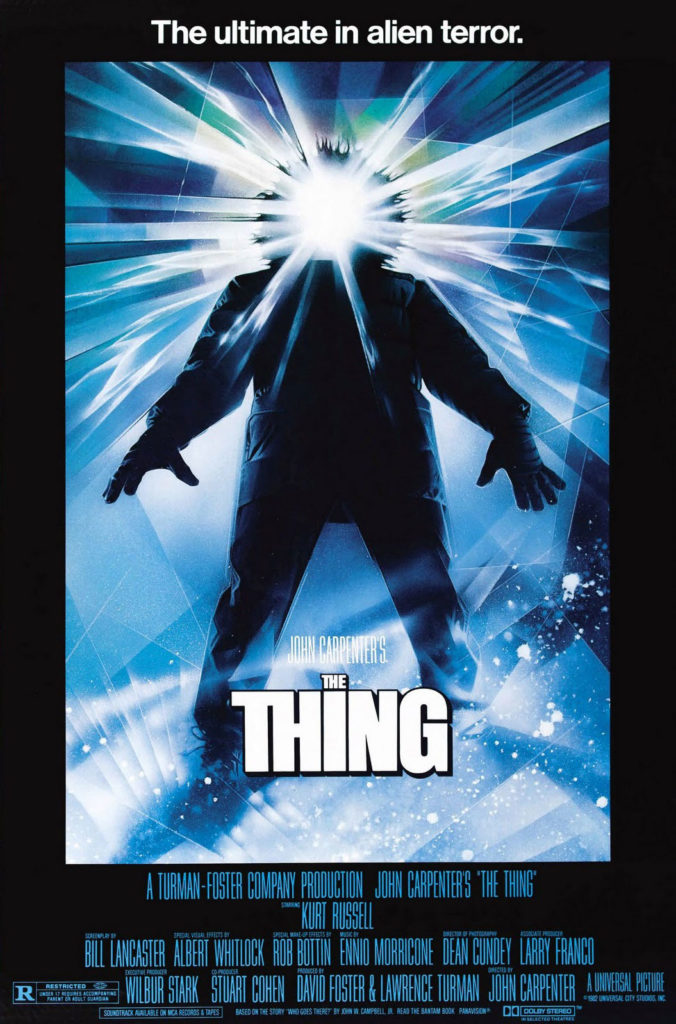

The 1980s were Carpenter’s most successful decade. He had Halloween on his CV and had put wads of cash in studio coffers. After Halloween his big screen efforts got darker and darker, reaching a nadir with 1982’s The Thing, an adaptation of the novella Who Goes There by John W. Campbell, Jr. (It was also a remake of an earlier Howard  Hawks film adaptation from 1951, but having hewed closer to the original source material than Hawks, Carpenter’s Thing bears resemblance to its predecessor in name only.)

Hawks film adaptation from 1951, but having hewed closer to the original source material than Hawks, Carpenter’s Thing bears resemblance to its predecessor in name only.)

Carpenter had a respectable budget for The Thing, a new experience for him. His previous effort, Escape from New York, had been a surprise hit on a shoestring budget, and Carpenter was rewarded with production values.

The film opened in the darkened theater at BAM, and the low rumble of a synthesized intro was paired with that font, proof positive of who had been sitting in the director’s chair. But with budget comes privileges, and one of those was a score by Ennio Morricone, oddly doing his best impersonation of John Carpenter music. The Thing hasn’t been re-released to theaters since it was first run, so the print that BAM acquired had some serious wear and tear. Stark, snow-covered landscapes that make up much of the visual power of the film were split into sections by the scratches that ran down the reels. Pops and quick green flashes were typical of the print throughout, but thankfully, there didn’t seem to be that many missing frames, and the color had held up well, despite countless hours of celluloid being bombarded with bright light. Better picture and sound quality could be had from a DVD, to be sure, yet, this was the big screen, where movies are meant to be seen — where immersion in story and environment is achieved with scale. Where you have to turn your head at times to take it all in. Where little details that escape the viewer on a tiny television screen all of a sudden become writ large, such as the nose ring that Richard Dysart is sporting, something I had never noticed before when it was only a quarter of an inch in size, at most, on the home set. But here, in the theater, that golden hoop reached proportions of confusing size, literally a foot or more across on extreme close-ups. “Did I really see that? Is he wearing a nose ring? Indeed he is! How odd.”

Richard Dysart is but one player in a twelve-man ensemble led by Kurt Russell, and including Keith David, Donald Moffat, and Wilford Brimley, among others. The men (no women in this film) are all situated at an Antarctic research station, researching who knows what, when an alien presence manifests itself. What follows is a familiar plot, one that has been represented ad nauseam in cinema, where the ensemble cast, in a confined and isolated environment, is whittled down by a homicidal monster. Where so many of these films have been handled poorly and unoriginally, Carpenter had an advantage. The source material was unique, and the film came out early enough in the genre of isolated, endangered monster fodder, that it plays as being derivative of only a handful of films, its predecessor and Alien in particular, instead of the massive library of films that today’s derivations steal from.

The monster in The Thing is a master of deception. It attacks and consumes its victim, but then it takes on all the characteristics of that victim in a feat of perfect imitation. Throughout the film, characters deal with death after grisly death, never quite sure which of their seemingly normal fellows is responsible for the carnage. Eventually, inevitably, trust breaks down, as each character can never be sure if the man next to him really is a man, or an alien imitation.

Carpenter does a decent job passing this tension on to the audience, and there are a few surprises here and there as the monster is forced to reveal itself, but the film is more effective as a gross-out vehicle than a psychological thriller. We wonder who the monster is, but we never enter the arena of paranoid delusion or confusion that true mind-fucks explore. The film is a series of strained interactions between characters interspersed with bloody, slimy, fiery, explosive appearances by the monster. These appearances rightly earned The Thing a reputation as being one of the grossest films ever made when it debuted.

Conceived and executed by Rob Bottin, the creature effects are elaborate and well done. The effects are still over-the-top today, far from tame, but judging from the laughs coming from the audience in the theater, and myself, they’ve crossed over a bit into caricature. A slimy six-legged creature with two heads just doesn’t hold the visceral disgust that today’s torture fare does. But, at least you won’t feel dirty after watching it.

The Thing is an enjoyable escape, despite the downward spiral of darkness that the characters find themselves in. It’s not as pretty as Alien, but how many movies can be that visually stunning? What you get with The Thing is a middle of the road director doing some of his best work. The story is good, the acting is good, there are some memorable scenes, and the ideas behind the plot stay with the viewer after the credits roll. There is just enough lack of resolution, just enough of the ‘what if’ about the story to keep a viewer thinking about it after the lights go up. No matter what kind of filmmaker a person happens to be, being able to keep the gears turning after the final credits roll is one of the marks of crafting a very good film.