So much horror is garbage that every occasion that sees a thoughtful and intelligent entry to the genre is a welcome reminder that a film that tries to scare the viewer to death is not automatically bad, or packed to the gills with cliché. While slasher flicks and the endless variations of SCREWED scenarios (see the review of Quarantine for a definition) are good fodder for the bloodthirsty moviegoer, the need for true quality is still there. All the camp, all the gore, all the outlandishness that gives the horror genre its identity is, unfortunately, as full of as much grace and depth as a carnival funhouse. Enjoyable as that can be, and as much as it keeps bloody murder from being weighed down by too much realism, a well-handled production with a talented cast, a talented director at the helm, and a good story can always be applauded as something that is, my goodness, actually worth seeing.

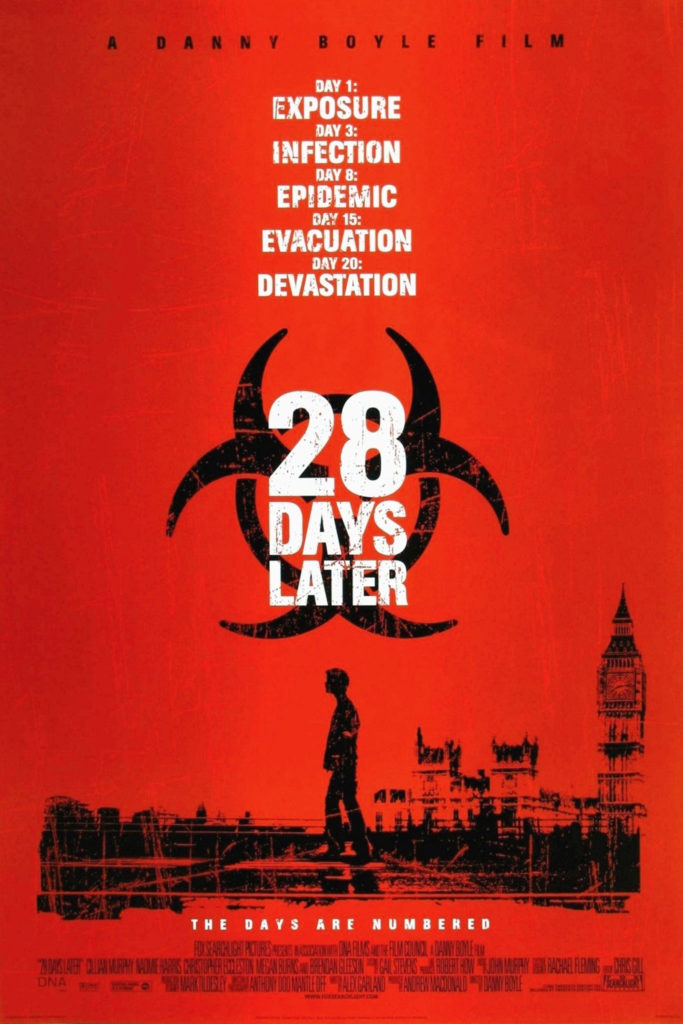

Filmmaker Danny Boyle leapt into the genre in 2002 with 28 Days Later, which refurbished post-apocalyptic zombie fare by tossing out all the old rules of undead hordes and making them frightening again. Not supernatural, these zombies are the result of science gone awry, infected with an artificial virus that will turn a normal person into a bloodthirsty monster in seconds. Zombie is a dated term in his film, as the infected are still human, but have had their intelligences and morals corrupted and twisted by the virus to the point they are little more than salivating, hemorrhagic killing machines. The infected mark the death of civilization not because the dead have risen, like in traditional zombie fare, but because, as one character points out, the virus has corrupted these poor souls to the point where the bloodlust rules so completely they can make no decisions regarding their own welfare, and can thus make no contribution to continuing the epoch of humankind. The film was intelligent, well-made, well-acted, and disturbing. The violence in it was exquisite. A bizarre compliment, but one that fits.

28 Days Later follows Jim (Cillian Murphy), who awakens from a coma in a London hospital following a motorcycle accident to find that the city is deserted, and has seemingly been so for weeks. He wanders the empty streets of central London looking for anyone who can tell him what has happened. Boyle filmed these scenes in the early morning, sun just peaking over the horizon, when it was easiest to close off streets and get shots quickly. The ghostlike quality of the lighting and the empty streets creates vast unease in the scene, as does a memorial wall posted with missing persons fliers, evocative of the weeks following the 9/11 attacks when the outside walls of hospitals in New York City were plastered with similar pleas.

Eventually Jim does find people alive, but realizes quickly that they are crazed, bloodthirsty killers, and the chase is on. Jim is rescued by Selena (Naomie Harris) and Mark (Noah Huntley), who lead him to safety. Mark doesn’t last all that long, but Jim and Selena find overnight refuge with father and daughter Frank and Hannah (Brendan Gleeson and Megan Burns, respectively), who have barricaded themselves in the upper floors of a tower block. The rest of the film follows this group of survivors as they try to make it to safety, leading to denouement in a mansion in the English countryside.

Murphy, Harris and Gleeson are excellent in this film, as are final act players Christopher Eccleston as the psychotic Major West and Ricci Harnett, who plays the wildly out of control Corporal Mitchell. That pair come close to stealing the film from its central protagonists and sending it off in a totally different direction, but Boyle sees that they are dealt with.

Five years on Juan Carlos Fresnadillo directed a sequel, and built effectively on the original.

28 Weeks Later, set after the infection has so devastated the island of Great Britain that the virus has seemingly died out, at first deals with the aftermath of the infection. A contingent of American peacekeepers has been tasked with overseeing the beginning phases of  reconstruction and repatriation of Great Britain, and are joined on the Isle of Dogs in London by British citizens who were lucky enough to be out of the country when the initial infection spread.

reconstruction and repatriation of Great Britain, and are joined on the Isle of Dogs in London by British citizens who were lucky enough to be out of the country when the initial infection spread.

Like the memorial wall in 28 Days Later, this sequel has an equally evocative moment, when it is revealed that the American zone of occupation is called the Green Zone. And thus we have international feelings for the United States in microcosm, tucked into a pair of horror films. In the first film, from 2002, the memorial wall created a visceral feeling, a solidarity with the United States, its moment of pain from only a year earlier still resonating with the filmmakers and viewers as a readily identifiable scene symbolizing human suffering. It wasn’t exploitative or campy, nor could it have been, having been filmed prior to 9/11. It was prescient recognition that mass tragedy and its aftermath redefine agony and show how people desperately search for closure. Fleeting though the shot was, it was quite weighted.

Flash forward to 2007, and the European perception of American arrogance in the years following the initial film permeates the sequel, beginning with a doe-eyed G.I. referring to this newest, fictional Green Zone. Like the memorial wall, the term ‘Green Zone’ is heavily weighted. For as long as history remembers the war in Iraq, ‘Green Zone’ will have a meaning, a connotation, and only in rare instances will any use infer something positive. Indeed, in 28 Weeks Later, American arrogance plays foil to the resilience of the virus, and the film almost falters when it becomes momentarily confusing who the audience should be rooting for: virus or America.

28 Weeks Later remains faithful to the original source material when needed, but unlike the first movie, which used lulls in action to build tension and frighten the audience, the sequel operates more as an extended chase movie once the virus manifests itself. It spreads so rapidly and so effectively among the small population of the Isle of Dogs that there is no time for the pastoral interludes of 28 Days Later. There are no moments of relaxation or introspection — only flight from danger.

The film does have its interludes, but Fresnadillo chooses far out gore as his escapism rather than lulls. Such moments aren’t on screen long, but they approach being plain wacky closely enough that they are out of place in a film that regards its subject matter so seriously in other instances. In other words: helicopter scene.

Like 28 Days Later, 28 Weeks Later is packed with a fantastic cast, including consummate pro Robert Carlyle (Don), whose character is just this side of cowardly, but is tortured enough about his decisions that he makes audience think about what they would do in a similar situation. Did he act cowardly, or did he just recognize accurately that he was in a no-win situation? Don’s wife Alice is played by Catherine McCormack, who splits her short performance between rational and psychologically destroyed with so little partition it could cause whiplash. Along with Carlyle and McCormack, other notable performances were turned in by Jeremy Renner (Doyle) and Idris Elba (General Stone), who have each continued their upward trajectories in the acting world since. That’s not everyone, but these were the best of a generally strong set of performances.

In many ways, 28 Weeks Later is a more watchable film than 28 Days Later. That’s not a knock on Boyle’s effort. Boyle created the more cerebral film, relying more on tension than flash to achieve his goals. In that, he crafted the better film.

Finally, where both films could have fallen into a trap that has bedeviled so many other horror films, they instead used a common device to effect. So many other horror and action films decide that the initial villains (zombies, monsters, or even tornados) are not threatening enough, and decide to add morally bankrupt or treacherous secondary characters to disguise the lack of mobility in the story. Both films employ this method. Only here, there’s nothing simplistic or clichéd, nothing that strains belief, when main characters find that the infected aren’t the only things they need to worry about.