We’re still burning through reviews that were intended for Tom Cruise month. This film is where I began to realize I might not want to watch 31 Tom Cruise movies:

I knew there were going to be some tough watches this month. It’s impossible to run through 31 of a star’s films and not find at least one film made for a completely different type of viewer than myself. In Legend, the 1985 fantasy film from writer William Hjortsberg and director Ridley Scott, that audience was one that likes a fairy tale. That’s what Legend is. It draws stark lines between good and evil, takes place in an enchanted forest, features a damsel in distress, and shares its overall creature aesthetic with Halloween displays at a big box store. Continue reading “Legend (1985)”

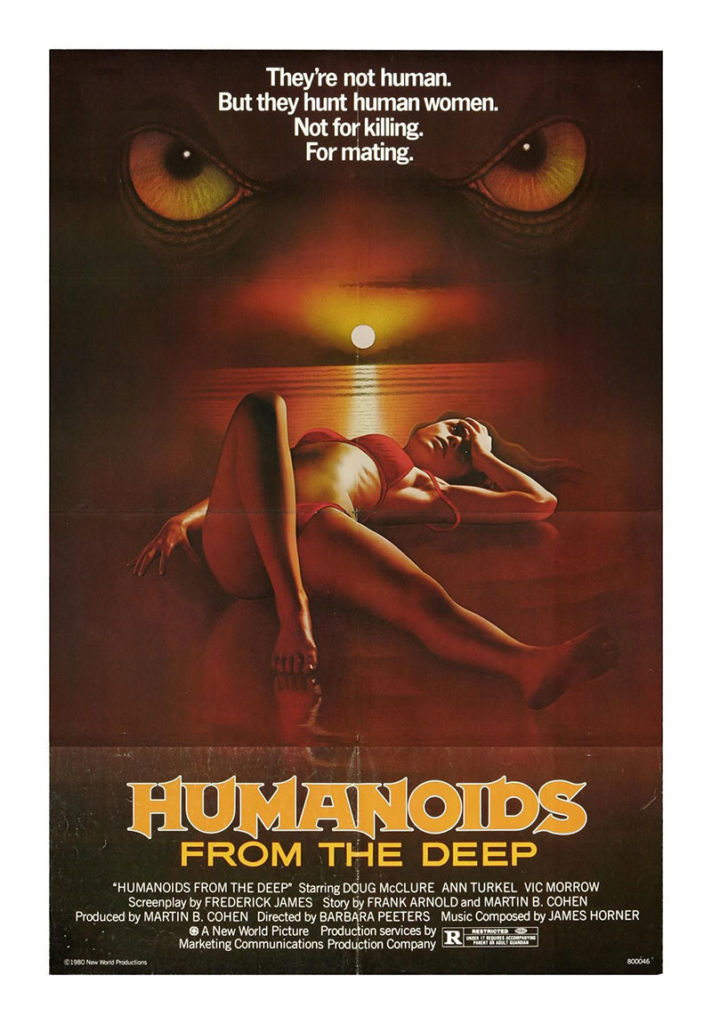

A viewer won’t find his name in the credits, but Humanoids from the Deep, an exploitative schlockfest from 1980, was produced by Roger Corman. He didn’t direct it and he didn’t write it, either. Barbara Peeters did the directing (with reshoots handled by an uncredited Jimmy T. Murakami), and Frederick James did the writing. But Corman’s hand is all over this film. It fits his demands at the time that cheap horror should be bloody, and feature some rape. Bloody is fine. Bloody is fun. Rape is really only useful in a horror flick if the mood a filmmaker is going for is revulsion. In a stupid monster flick, it’s overkill. Still, it doesn’t ruin too much of the fun of this putrid mess. Other stuff is responsible for that.

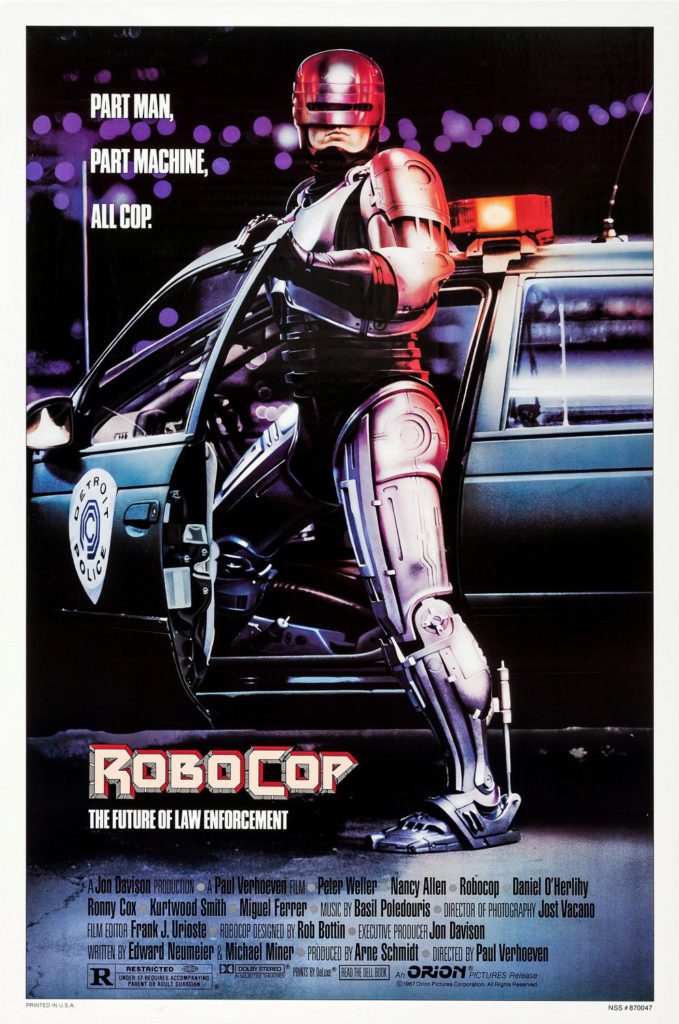

A viewer won’t find his name in the credits, but Humanoids from the Deep, an exploitative schlockfest from 1980, was produced by Roger Corman. He didn’t direct it and he didn’t write it, either. Barbara Peeters did the directing (with reshoots handled by an uncredited Jimmy T. Murakami), and Frederick James did the writing. But Corman’s hand is all over this film. It fits his demands at the time that cheap horror should be bloody, and feature some rape. Bloody is fine. Bloody is fun. Rape is really only useful in a horror flick if the mood a filmmaker is going for is revulsion. In a stupid monster flick, it’s overkill. Still, it doesn’t ruin too much of the fun of this putrid mess. Other stuff is responsible for that. Dystopian future societies are the stuff dreams are made of. They are what grow from the seeds of our own decadence and shallowness. The moral bankruptcy, and sometimes outright horror, of the settings of films like Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, THX 1138, Escape from New York, and Soylent Green wouldn’t be possible if writers and directors didn’t look around them and see the lightning speed with which we throw ourselves into unknown futures, sometimes without regard for so many of the present realities which work so well and don’t need change. The ever-present message is that change, sometimes jarring change, is inevitable. Films that look to the future warily revolve around placing the viewer in the role of Rip Van Winkle. When the theater lights dim, the familiar world of today dissolves into the freak show of tomorrow. The overriding questions always being: Why are the people onscreen comfortable with this? Why doesn’t everybody see how wrong things are?

Dystopian future societies are the stuff dreams are made of. They are what grow from the seeds of our own decadence and shallowness. The moral bankruptcy, and sometimes outright horror, of the settings of films like Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, THX 1138, Escape from New York, and Soylent Green wouldn’t be possible if writers and directors didn’t look around them and see the lightning speed with which we throw ourselves into unknown futures, sometimes without regard for so many of the present realities which work so well and don’t need change. The ever-present message is that change, sometimes jarring change, is inevitable. Films that look to the future warily revolve around placing the viewer in the role of Rip Van Winkle. When the theater lights dim, the familiar world of today dissolves into the freak show of tomorrow. The overriding questions always being: Why are the people onscreen comfortable with this? Why doesn’t everybody see how wrong things are?