Dystopian future societies are the stuff dreams are made of. They are what grow from the seeds of our own decadence and shallowness. The moral bankruptcy, and sometimes outright horror, of the settings of films like Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, THX 1138, Escape from New York, and Soylent Green wouldn’t be possible if writers and directors didn’t look around them and see the lightning speed with which we throw ourselves into unknown futures, sometimes without regard for so many of the present realities which work so well and don’t need change. The ever-present message is that change, sometimes jarring change, is inevitable. Films that look to the future warily revolve around placing the viewer in the role of Rip Van Winkle. When the theater lights dim, the familiar world of today dissolves into the freak show of tomorrow. The overriding questions always being: Why are the people onscreen comfortable with this? Why doesn’t everybody see how wrong things are?

Dystopian future societies are the stuff dreams are made of. They are what grow from the seeds of our own decadence and shallowness. The moral bankruptcy, and sometimes outright horror, of the settings of films like Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, THX 1138, Escape from New York, and Soylent Green wouldn’t be possible if writers and directors didn’t look around them and see the lightning speed with which we throw ourselves into unknown futures, sometimes without regard for so many of the present realities which work so well and don’t need change. The ever-present message is that change, sometimes jarring change, is inevitable. Films that look to the future warily revolve around placing the viewer in the role of Rip Van Winkle. When the theater lights dim, the familiar world of today dissolves into the freak show of tomorrow. The overriding questions always being: Why are the people onscreen comfortable with this? Why doesn’t everybody see how wrong things are?

Simply put, because that’s how things in the future work. People in the future grow up among the bizarre, things we wouldn’t recognize, as though these were the normal conditions of existence, rather than a manufactured reality that mankind has created for itself. The irony is, of course, that we, in real life, away from the fantasies of Hollywood, live like these silver screen wraiths, embracing the fast pace of technological advance, throwing off the yoke of millennia of human history to embrace the dictates of the electronic age. Implicit in films that depict the future is that civilizational advance is a given, destroying the ways and mores of the past, creating something unrecognizable to those who weren’t witness. This resonates because that is exactly how our ancestors would feel would they awake in today’s world.

Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven has explored the future in a unique trilogy of films, unrelated in plot or characters, but all showcasing possible outcomes were we to fail to remain vigilant about our freedoms. Verhoeven’s youth in Nazi-occupied Holland seems to provide much of the color and source of his inherent distaste for authority. In Paul Verhoeven’s visions, corporations and fascists (both interchangeable) continuously look to gain power at the expense of ordinary men and women. In two of the films, Robocop and Total Recall, the heroes are also victims of the power elite, while the third, Starship Troopers, features worldwide fascism elevated to a horrifying status quo. There is no dissent or rebellion in this latter film. Instead, it relies on the audience’s perceptions to recognize it as satire.

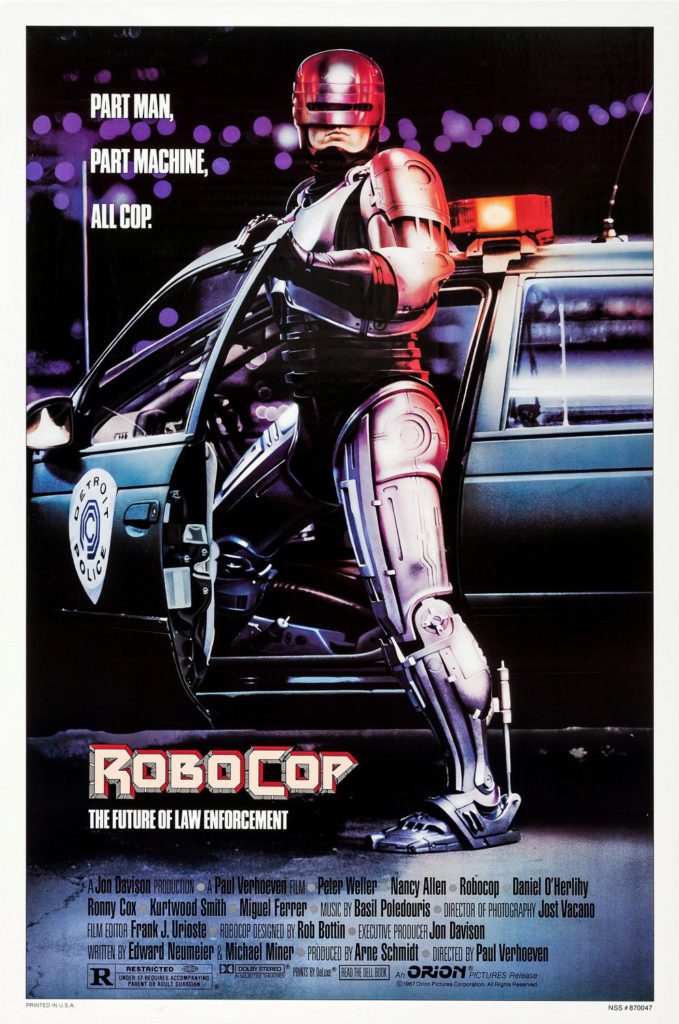

From 1987, Robocop picks at the corpse of Detroit. An easy target, like New York in a disaster movie, when telling a story of crime run rampant, a city consumed by its own decay, Detroit is an unfortunately logical setting. Even today, more than twenty years after Robocop was released, after the pendulum of urban crime in America swung the other way, largely erasing the fears which spawned films like Robocop, Detroit is still struggling, making the film’s continued relevance disappointing.

But in saying that, it’s important to note that very relevance is part of what keeps Robocop worth watching. The other part is, of course, the character of Robocop himself.

Peter Weller is a cop and a family man named Murphy. Despite the dangers of his job (regular street duty in a city that eats police officers alive), he is dedicated yet strangely aloof. He is ready to employ deadly force at a moment’s notice, understandable since all criminals in this Detroit of the future seem to be sociopaths, but he doesn’t seem all that bothered by the downward spiral that traps society around him. He is supposed to be one of those that checks this advance towards oblivion, but he is wooden. Being a cop is strictly a job for this fellow, despite his enthusiasm for it. One has to wonder if Murphy would be a cop if there weren’t heads to bust, bad guys to shoot. He eventually comes under the guns of Clarence Boddicker (played by a miscast Kurtwood Smith) and his gang. Murphy is brutally murdered in a hail of gunfire. But if he were really dead, Robocop would be a short film.

As it turns out, Murphy’s body is used to make a robotic supercop under the aegis of the ever-present megacorporation OCP, which holds the contract for a privatized police force in Detroit. The remainder of the film concerns Murphy’s awakening memories of his past life and his desire to avenge his death while upholding the law. He tracks down the criminals responsible and finds that they take their directions from the same people that issue his orders. Of course, trouble ensues as he shoots his way closer to the roots of Detroit’s corruption.

The story is predictable. The production is flamboyant. However, watch closely and there is a fair amount of depth in Robocop. As social commentary it has a hard time being matched in popular culture, despite its simplicity. Perhaps, even, the simplicity is part of the point Verhoeven is trying to make. Little indictments of crass commercialism crop up throughout Robocop, reminding the viewer that crime is not the only source of society’s fall. Propaganda and advertising are mutually culpable.

In Robocop, Detroit has been turned into a commentary on the ridiculousness we see around us every day. In 1987 it was not all that outrageous to think that our cities would continue to be consumed by crime. It was not outlandish to think that twenty years from then, there would be master criminals like Clarence Boddicker running around, racking up body counts that resemble terrorists more than bank robbers. Robocop is about an America that has totally lost its bearing. At the time it was made, there was little promise that public officials could keep such a nightmare from happening in this country. The economic prosperity of the 1990s thankfully closed the door on such a possibility.

One thing that was visionary about Robocop is the role a monopolistic corporation plays in the film. Privatization wasn’t exactly a catchphrase during the Reagan administration. It took until Bush came to power in 2001 for the shift of public assets to corporations to really take hold. Robocop was ahead of the curve in showing public services in the hands of for-profit businesses. Of course in the movie, OCP has its hands in everything, making Detroit a company town from the boardroom on down. It can be argued with veracity on both sides just how much a city like Detroit has been under the sway of corporate money, but the point of Robocop is that there is no longer backroom influence and malfeasance. OCP runs Detroit by law, by contract, its opacity par for the course, not a violation of the public trust. Despicable, yes, but after eight years of conservative rule, not as outlandish an idea as it was back in 1987.

Robocop is garish and loud. There are big explosions and cheesy lines. On the surface, the film has no depth at all. It looks and plays like a shoot-em-up. Take a minute to look closer, however, and one notices that this film has a lot to say about the direction we as a country are headed. It reminds us to pay attention to our ills, to pay attention to overreach. It begs us to watch what our government is doing in the name of keeping us safe, and to keep a close eye on any business that claims to have the public interest ahead of its bottom line.