Gritty New York City cop dramas are stylistically different from gritty Los Angeles cop dramas. It’s only partly due to setting. It would be hard for a film to ignore the differences between the coasts, but as far apart as the Eastern Seaboard and SoCal are, geographically and culturally, these differences are not what set cross-continental police flicks and television series apart. Just doing a loose word association, when I think NYC cop drama, my first thought is Law & Order and all of its iterations — police procedurals that follow detectives. After that I drift back to films from the past like The French Connection, Serpico, Fort Apache the Bronx, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Across 110th Street, even Bad Lieutenant. These films represent my own personal biases, but they all adhere to a palate of sorts that is broadly representative of New York City cop films.

Gritty New York City cop dramas are stylistically different from gritty Los Angeles cop dramas. It’s only partly due to setting. It would be hard for a film to ignore the differences between the coasts, but as far apart as the Eastern Seaboard and SoCal are, geographically and culturally, these differences are not what set cross-continental police flicks and television series apart. Just doing a loose word association, when I think NYC cop drama, my first thought is Law & Order and all of its iterations — police procedurals that follow detectives. After that I drift back to films from the past like The French Connection, Serpico, Fort Apache the Bronx, The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, Across 110th Street, even Bad Lieutenant. These films represent my own personal biases, but they all adhere to a palate of sorts that is broadly representative of New York City cop films.

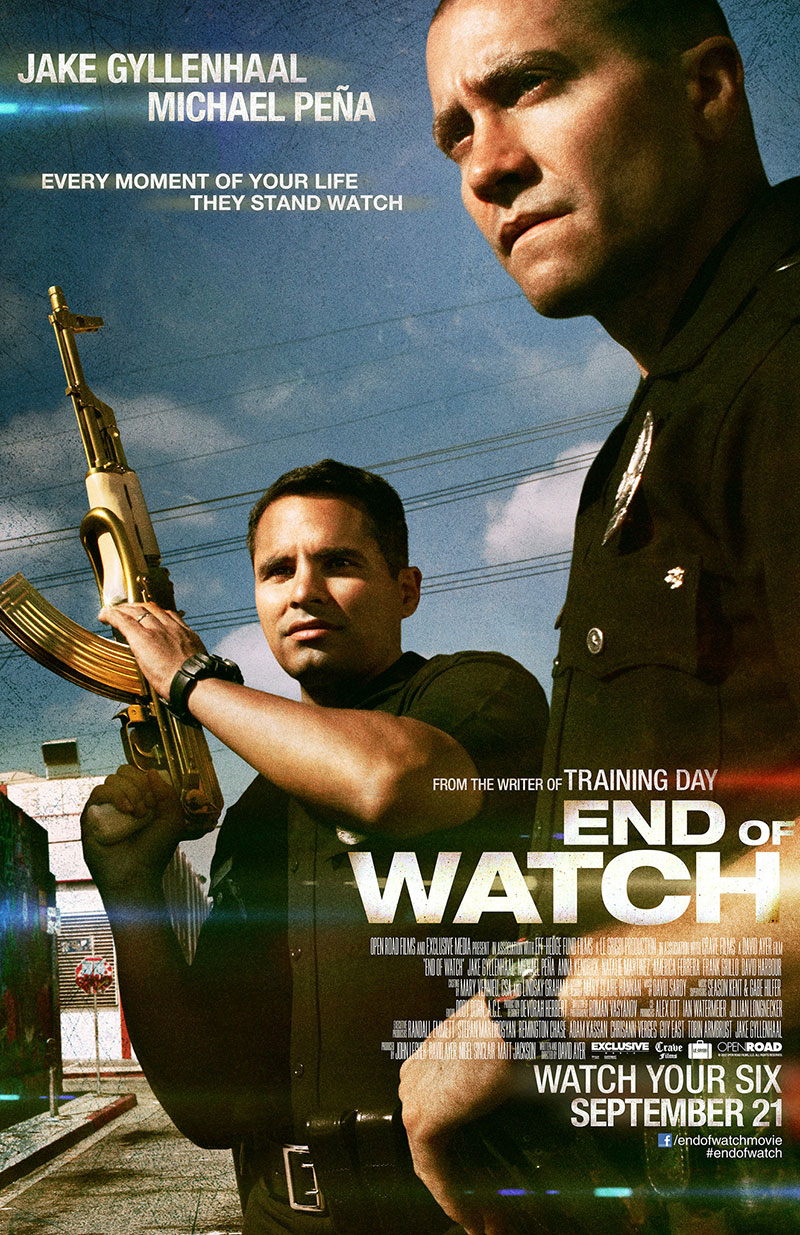

Across the farmlands, the plains, the mountains and the deserts, Los Angeles has been building its own mythos regarding the LAPD on film. After decades following the cop as superman (think Lethal Weapon, Cobra, etc.), that model looks set to be replaced by episodes of Cops. I’m not joking. Some of the best work regarding LAPD officers of late hasn’t involved huge explosions and guns that never run out of ammo. It hasn’t been the lone detective doggedly pursuing the impossible murder case. It hasn’t been buddy movies. It’s been the uniformed officer. Continue reading “End of Watch”

Taylor Kitsch just had a bad year. He starred in three major release films. How can that possibly be bad? The three films were Battleship, John Carter, and Oliver Stone’s latest ham-fisted effort, Savages. Three films, three disappointments, and Mr. Kitsch has suddenly moved into Ryan Reynolds territory as the latest bankable star that turned out to be not so bankable. It isn’t all his fault, though. John Carter was doomed from the start, and Battleship was so awful, a cavalcade of thespians from the Royal Shakespeare Company couldn’t have saved it.

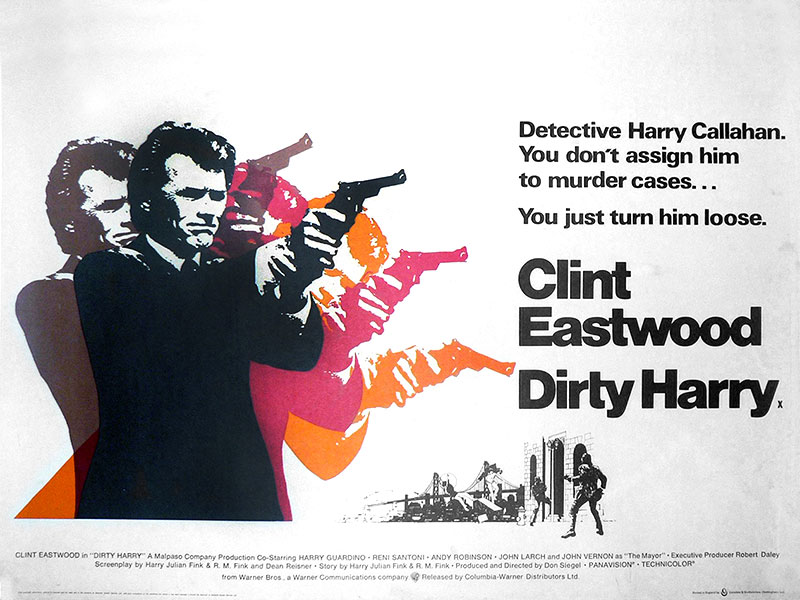

Taylor Kitsch just had a bad year. He starred in three major release films. How can that possibly be bad? The three films were Battleship, John Carter, and Oliver Stone’s latest ham-fisted effort, Savages. Three films, three disappointments, and Mr. Kitsch has suddenly moved into Ryan Reynolds territory as the latest bankable star that turned out to be not so bankable. It isn’t all his fault, though. John Carter was doomed from the start, and Battleship was so awful, a cavalcade of thespians from the Royal Shakespeare Company couldn’t have saved it. The tough-nosed cop with a disdain for the rules is a staple in film. Always butting heads with desk-bound lieutenants and mayors more concerned with getting reelected than cleaning up the streets, this breed of law enforcement officer has little time for procedure or the niceties of due process. Largely a fabrication of Hollywood, this cop operates in a world where the worse the crime, the more likely the guilty will go free due to the dreaded plot device known as “technicalities.” It’s all the more galling because there is never any doubt to the audience or to the hero that the bad guy is bad. Letting the bad guy go free because his rights were violated is nothing less than a miscarriage of justice, and it’s always left up to the hero cop to right such grievous wrongs. No film comes to mind that explored these ideas more effectively than 1971’s Dirty Harry.

The tough-nosed cop with a disdain for the rules is a staple in film. Always butting heads with desk-bound lieutenants and mayors more concerned with getting reelected than cleaning up the streets, this breed of law enforcement officer has little time for procedure or the niceties of due process. Largely a fabrication of Hollywood, this cop operates in a world where the worse the crime, the more likely the guilty will go free due to the dreaded plot device known as “technicalities.” It’s all the more galling because there is never any doubt to the audience or to the hero that the bad guy is bad. Letting the bad guy go free because his rights were violated is nothing less than a miscarriage of justice, and it’s always left up to the hero cop to right such grievous wrongs. No film comes to mind that explored these ideas more effectively than 1971’s Dirty Harry.  Christopher Nolan has wrapped up his epic interpretation of the Batman saga, and the viewing public has benefited greatly. After two of the most epic and well-made superhero films of all time, and fine films in their own right, the tale comes to an end this summer. Nolan, and his screenwriter brother Jonathan, should be credited with legitimizing and dragging into believability an aged franchise that at times wears its history and legacy as a seventy-year-old burden.

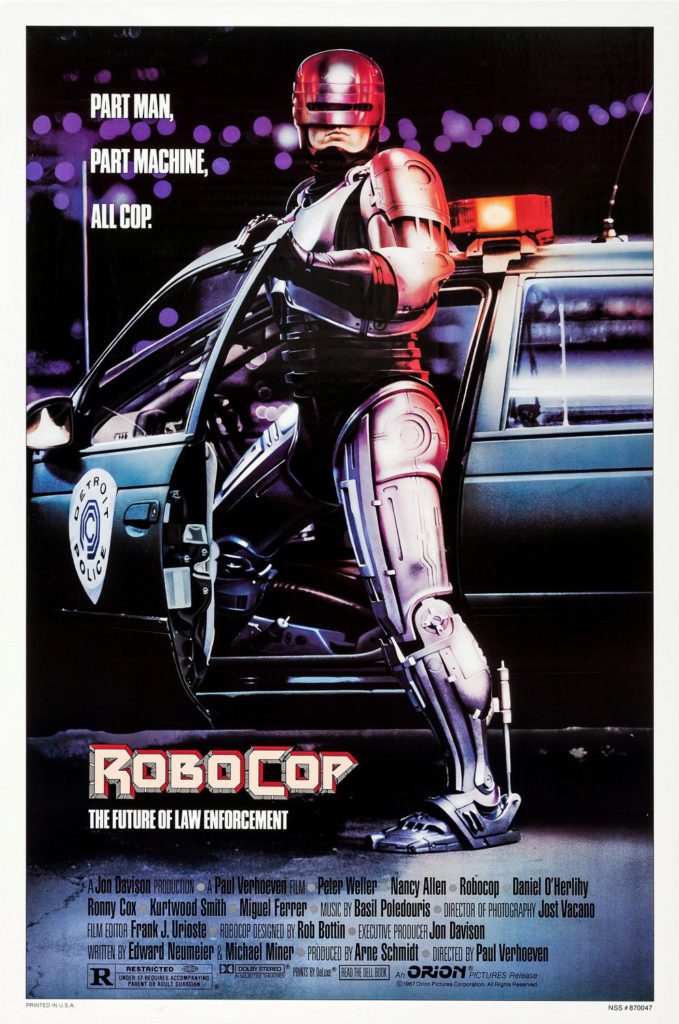

Christopher Nolan has wrapped up his epic interpretation of the Batman saga, and the viewing public has benefited greatly. After two of the most epic and well-made superhero films of all time, and fine films in their own right, the tale comes to an end this summer. Nolan, and his screenwriter brother Jonathan, should be credited with legitimizing and dragging into believability an aged franchise that at times wears its history and legacy as a seventy-year-old burden. Dystopian future societies are the stuff dreams are made of. They are what grow from the seeds of our own decadence and shallowness. The moral bankruptcy, and sometimes outright horror, of the settings of films like Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, THX 1138, Escape from New York, and Soylent Green wouldn’t be possible if writers and directors didn’t look around them and see the lightning speed with which we throw ourselves into unknown futures, sometimes without regard for so many of the present realities which work so well and don’t need change. The ever-present message is that change, sometimes jarring change, is inevitable. Films that look to the future warily revolve around placing the viewer in the role of Rip Van Winkle. When the theater lights dim, the familiar world of today dissolves into the freak show of tomorrow. The overriding questions always being: Why are the people onscreen comfortable with this? Why doesn’t everybody see how wrong things are?

Dystopian future societies are the stuff dreams are made of. They are what grow from the seeds of our own decadence and shallowness. The moral bankruptcy, and sometimes outright horror, of the settings of films like Blade Runner, A Clockwork Orange, THX 1138, Escape from New York, and Soylent Green wouldn’t be possible if writers and directors didn’t look around them and see the lightning speed with which we throw ourselves into unknown futures, sometimes without regard for so many of the present realities which work so well and don’t need change. The ever-present message is that change, sometimes jarring change, is inevitable. Films that look to the future warily revolve around placing the viewer in the role of Rip Van Winkle. When the theater lights dim, the familiar world of today dissolves into the freak show of tomorrow. The overriding questions always being: Why are the people onscreen comfortable with this? Why doesn’t everybody see how wrong things are?