Christopher Nolan has wrapped up his epic interpretation of the Batman saga, and the viewing public has benefited greatly. After two of the most epic and well-made superhero films of all time, and fine films in their own right, the tale comes to an end this summer. Nolan, and his screenwriter brother Jonathan, should be credited with legitimizing and dragging into believability an aged franchise that at times wears its history and legacy as a seventy-year-old burden.

Christopher Nolan has wrapped up his epic interpretation of the Batman saga, and the viewing public has benefited greatly. After two of the most epic and well-made superhero films of all time, and fine films in their own right, the tale comes to an end this summer. Nolan, and his screenwriter brother Jonathan, should be credited with legitimizing and dragging into believability an aged franchise that at times wears its history and legacy as a seventy-year-old burden.

Only the most basic of continuity from the DC Comics characters remain in the Nolan retelling. Ra’s al Ghul? Dead after one film. Joker? One film and done (extenuating circumstances do apply). Two-Face? Dead, and a far cry from the criminal mastermind of the comics. Even Scarecrow, a stalwart of the Rogues Gallery, saw his menace pass with Batman Begins, settling for mere cameo in the subsequent films.

One of the things regular readers of the serialized Batman comics can count on is the lack of finality in any story. Sure, Joker, or Killer Croc, or Zsasz will wreak their havoc upon Gotham City and its inhabitants, but Batman always prevails, and Arkham Asylum welcomes the vanquished villain with open, inadequately secured arms, sure to let their ward escape to challenge the Masked Manhunter again...editors willing.

It’s a never-ending cycle driven by the ongoing nature of the comics and their sales. No great villain can spend all that much time locked up if it is a dynamic creation that readers like to see. But in the continuity Nolan has created over eight hours or so of film, a massive compression of the Batman story has taken place. Much of the baggage has been jettisoned.

Rather than being Gotham City’s constant, anguished hero, Bruce Wayne has a penultimate plan, one where Batman is an effective salve against the criminal disease that plagues the city — his purpose to awaken a good citizen of Gotham, one willing to take up the anti-crime crusade with the mantle of legitimacy, allowing Batman to fade into myth. The Bruce Wayne of the comics has never had such faith in the inevitable appearance of an inspired savior. He believes he is the only one with the will and fortitude to make a difference. Leave the fight to someone else? Never. (Most of the time never. No need to get into minutiae.)

It’s part of the realism of Nolan’s stories that Batman has limits. There are only so many beatings, so many injuries, that a real person can sustain before they reach the limits of endurance. It doesn’t matter how many obscure martial arts masters one meditates with in the Himalayas. Eventually, one’s knees will give if every night is spent picking fights with thugs. Nolan even acknowledges this non-reality in showing Bruce Wayne miraculously recovering from an eight-year limp by, essentially, squeezing his leg. We’ll let it slide. The limp had to go to get Wayne back in the suit.

It’s in that dilapidated state that the viewer sees Bruce Wayne when The Dark Knight Rises begins.

After the battle against the Joker in The Dark Knight, culminating in the death of Harvey Dent, Batman became a hunted criminal. Rather than clear his name, Wayne and police commissioner James Gordon have decided to let Batman take the blame for Dent’s death, transforming the slain district attorney into a symbol of hope, covering up the fact Dent really represented a victory for the Joker. Dent’s false legacy is used to pass legislation that has crippled organized crime in Gotham City.

Eight years pass, and in that time, no more Batman, and no appearances by criminals from the Rogues Gallery. The comics could never tolerate such a period of calm. Eight years without Batman? What about Riddler? The Penguin? Poison Ivy? Mad Hatter? The Penny Plunderer? There is always a reason to throw on the tights and go to war in the comics universe. It’s part of the brilliance of the Nolan continuity that the story owed no allegiance to characters never alluded to on screen.

Ra’s, Scarecrow, Joker, Two-Face — enough evil for any man to face in a lifetime. And thus, a Howard Hughes-esque seclusion for Bruce Wayne.

But a new villain makes his presence known in Gotham: the mysterious and menacing Bane. To the confusion of the audience, he is a ruthless figure with puzzling motivations. He is painted as a mercenary, but clothes himself as a terrorist with a murderous grudge. Which is he, a contractor or a true believer?

The choice of Bane as the villain in this film is a curious one for Nolan. Bane has a pedigree in the DC universe dating back twenty or so years ago. He has made numerous consequential appearances in the comics, notably being the villain that knocked Bruce Wayne out of action for over a year, allowing the poorly written and poorly considered Jean-Paul Valley to become Batman in the early 1990s.

Bane was a transparent effort to craft a villain which would shake up the Batman comics and generate some buzz and increased sales. His story and defeat of Batman in the Knightfall storyline was contrived, cheap in writing and execution, and inevitably led to the reinstatement of Bruce Wayne as Batman after the editors determined a sufficient amount of time had passed. Further appearances of Bane felt like a desperate attempt to confer continued relevance on a character that had served his purpose fully in a one-page panel where he snaps Batman’s back.

The worst thing about Bane is that his appearance signaled an end to a time when the Batman titles were story driven, rather than guided by the over-the-top machinations of Batman and his enemies. It was only a short window between what is referred to as pre-Crisis and when Bane first appeared, but it was a sweet time, and resulted in some of the most lasting Batman stories, tales that still top ‘best of’ lists today.

Bane, in short, is a joke. A third-tier Batman villain artificially elevated to prominence like a newcomer in the WWE whom Vince McMahon decided to give some juice because Smackdown was lagging in ratings. Bane is a failed experiment, a tawdry diversion from what can make the comics great. Featuring Bane as the villain in The Dark Knight Rises is a disappointment. It was a choice that was intriguing only in its ability to challenge Nolan as a storyteller. Elevating a character lacking in depth and sincerity to such a degree while requiring he carry the final act of the greatest superhero trilogy of all time is ambitious, indeed.

Was Nolan up to the task? Could he take such dreck and make it compelling through sheer will and talent?

Yes, and no.

Nolan’s Bane does benefit from the touch of a deft storyteller, but Nolan and his brother added none of the much-needed depth to Bane, unlike the magic they worked with Joker and Scarecrow. Even with the big reveal that dominates the final act of the film, Bane remains a murky presence throughout The Dark Knight Rises — little understood, little sensible, little reasonable. If the intent was to make Bane the embodiment of evil, then the effort was a failure. The comparison to professional wrestling made earlier becomes apt. Bane, like in the comics, is a heel brought in for dramatic effect, a means to get the face motivated, to get Bruce Wayne to once again take up the mantle of the bat.

It does not help matters that the Nolan films have never concerned themselves with the small story. One of the best runs in the Batman comics came right around the time the first Tim Burton film came out, when Alan Grant and John Wagner took over writing duties on Detective Comics, the first regular Batman title. A creative split soon led Wagner to cede duties solely to Grant. As a new contributor to the title, Grant began slowly, bringing Batman back to the streets of Gotham City, fighting crime on a human scale, more in tune with the idea of a crime fighter working to prevent more tragedies like those that took his parents.

The Alan Grant era was glorious in the Batman continuity, but then Bane reared his ugly head. Since that time, Batman stories have been consistently overwrought, with the supercriminals’ main concern being the destruction of Gotham City and/or Batman, and rarely their own personal gain. It made for a ridiculous escalation in the gravity of the tales to the detriment of the comics.

Nolan has been walking a fine line with his films. Batman Begins and The Dark Knight have been very much kin to the existential drivel of the last twenty years of the comics, but talent and skill have kept things grounded, even in the face of outrageous eccentricities. It’s by utilizing Bane, and surrounding him with a story that such a figure demands, when the scales finally tip.

The Dark Knight Rises is a good film. It’s not the worthy finale to the trilogy audiences were expecting. Its villain is shallow, with motivations that remain mysterious until an hallucination explains it all to Bruce Wayne and audience alike. Michael Caine does little more than weep through his lines, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s character seems to exist for no other reason than to give the audience closure in the end. Seriously, had Gary Oldman not spent most of the film in a hospital bed, his James Gordon could have been the character performing all of Levitt’s scenes.

The film is far too long, yet still manages to introduce a romantic subplot that proceeds too quickly to be believable.

Christian Bale is excellent as Bruce Wayne. His open-mouthed growl as Batman, however, makes a viewer glad the caped crusader has little screen time.

Similarly, Anne Hathaway is a fine Selina Kyle, but once the mask was on, as Catwoman, I couldn’t help but find myself not buying any of it. This isn’t just a lack of realism. Rather, I found myself running through a list in my head of actresses I would have rather seen wearing the mask. She was miscast.

Finally, there is Tom Hardy as Bane. Hardy is a very talented actor. If a filmmaker wishes him to, he will deliver a physical performance for the ages. In The Dark Knight Rises, he was segregated behind a plastic mask, and had to rely on gesticulation and a menacing physical presence to get his performance across. He was oh, so close, but was foiled by the awful sound mixing throughout the film.

Sound mixing is one of those aspects of a film casual viewers are not supposed to notice. When a film gets nominated for an Oscar for sound, it gets greeted with a shrug by the movie-going public. But the sound in The Dark Knight Rises is noticeably bad. Much, if not most, of Bane’s dialogue is unintelligible. All of it I had to strain to understand. Even in scenes with other characters, all dialogue was often drowned out by overbearing music.

The degree of difficulty in following up The Dark Knight means this film deserves a lot of leeway. Stepping back, The Dark Knight Rises is an achievement, but going into the film, a viewer must be prepared for a less coherent, less intelligent, more senseless, and more rote film than that which came before.

The Dark Knight Rises is going to be the last Batman film for a while, so a viewer might want to check out one of the older films.

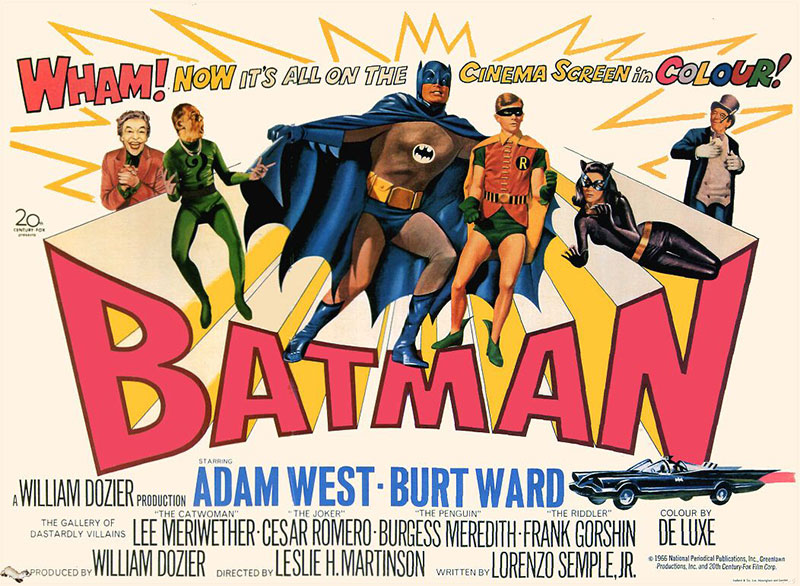

For a total contrast to the Nolan films, one can’t do better than 1966’s Batman, based on the campy television series of the same name.

Recently, Grant Morrison, the great comics writer, watched all the Batman films, and a good deal of the television series. In a short blurb about the 1966 film, he pointed out that it was the type of movie that children love, adolescents loathe, and adults find hilarious. I agree.

When I first began reading Batman I was around twelve. The Batman universe had just gone through seismic changes. Frank Miller had penned the astounding Year One and Dark Knight Returns stories, and Jason Todd, the second Robin, had just been killed off (by the readers in a phone poll, no less). Batman was redefined as a darker character (a process begun in the late 60s, reaching its culmination in the mid 80s). This redefining led directly to the resurgence of what had been a lagging franchise, just in time to provide impetus for the Tim Burton film.

Batman was a tragic loner. He relied on no one but himself and entertained no challenges to his rigid worldview. He was the perfect superhero for adolescent boys. The idea that Batman was once upon a time an absurdist slapstick hero was anathema to what DC was selling in the 80s. Indeed, to this day, the Adam West/Burt Ward era of Batman is unavailable on legitimate home media, the victim of contract disputes. Or, as the rumor mills claim ominously, the result of DC’s disownment of a Batman continuity that exists in such contrast to the character we know today, and which fills their coffers.

Thank goodness, then, for Nick at Nite.

Back when Batman became a moneymaker again, Nickelodeon began showing the 1960s TV show in syndication, and I got to see DC’s redheaded stepchild. I eventually secured a copy of the movie that was produced between the first and second seasons. I was no more horrified than I had been at the sight of the television show.

Watching the 1960s Batman movie in this day and age, as I did after returning home from The Dark Knight Rises, I was greeted with a bawdy ridiculousness that I loved.

Batman, the 1966 film, is hilarious.

Building on the success of the first season  of the television show, Adam West and Burt Ward reprise their roles as Batman and Robin, Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson being their alter egos. Because one villain is not enough for the silver screen, the dynamic duo face not one, not two, not three, but four arch-criminals. Riddler (Frank Gorshin), Catwoman (Lee Meriwether), Penguin (Burgess Meredith!), and the Joker (Cesar Romero) team up to take on Batman. The four have their sites set higher than dominating Gotham City. They want to control the world, and only Batman can stop them. Once again, a very big story makes its way to the screen, but there is one difference that makes it okay for this movie to completely ignore a smaller scale story.

of the television show, Adam West and Burt Ward reprise their roles as Batman and Robin, Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson being their alter egos. Because one villain is not enough for the silver screen, the dynamic duo face not one, not two, not three, but four arch-criminals. Riddler (Frank Gorshin), Catwoman (Lee Meriwether), Penguin (Burgess Meredith!), and the Joker (Cesar Romero) team up to take on Batman. The four have their sites set higher than dominating Gotham City. They want to control the world, and only Batman can stop them. Once again, a very big story makes its way to the screen, but there is one difference that makes it okay for this movie to completely ignore a smaller scale story.

No one in this film, not a single member of the cast, plays this tale straight. At times is feels like a repertory performance at Pee-Wee’s Playhouse. The colors are saturated, the costumes outlandish, and the performances...not quite dripping with sober seriousness.

Despite what one might think about Adam West, he was the standout in this film. There was no way Batman could have succeeded without the affected sense of gravitas West gave to the dual roles of Bruce Wayne and Batman.

I showed a scene from the film the other day to Daily Exhaust Mike and he compared West to William Shatner. I disagree. In Star Trek, Shatner was playing it straight. In Batman, West was clearly embracing the absurd. Batman is a comedy, and West plays it as such. And his natural comedic timing is impeccable. Sometimes a dramatic actor finds a gift for comedy despite where they picture the trajectory of their careers. West is amazing in Batman. He stretches comedic legs as both Batman and Bruce Wayne. His scenes while he is wooing Catwoman in disguise are precious, combining clueless smoothness with creepy smarminess in such an innocent way that it can’t be held against him.

Opposite him was Burt Ward, who spent most of the film enthusiastically spouting his catchphrase, “Holy (blank), Batman!!” — my personal favorite being, “Holy heart failure, Batman!!” after Batman manages to dispose of a particularly precocious explosive. Like West, Burt Ward had a hard time finding work after the TV show was cancelled, but there is no reason to look back on this role with shame. Ward was rambunctious, and even showed élan in his portrayal of Robin.

Of course, Batman does not rate as a great movie, but I do think it has an argument for being a sorely underrated comedy. Unlike so many of Hollywood’s more celebrated comedies, it maintains an even pace throughout, never becoming bogged down in third act seriousness. Check it out.

Addendum: Lo and behold, a couple of years after I penned this piece, someone came along and figured out the disputes, and the long-sought Batman television show was finally given a home video release.