Always beware when a series of films has been labeled a franchise. Often it can mean that any effort to bring quality to the screen has been abandoned to embrace the industry’s insulting perceptions of mass taste. Such has been the fate of the Alien series of movies. The last entry that remained within the original continuity, Alien: Resurrection, was so awful it effectively killed the series. Since then, it has truly embraced the franchise label, making reality longstanding plans to team up with the Predator franchise, following a trail the comic book wings of the two brands began blazing in the 1980’s.

Brand is a label even more abhorrent when applied to film than franchise. Not many film lovers like to think about the accuracy of these labels. The reality is, films made for wide release have profit as their prime motivator. Quality is a secondary consideration if the film can make money without it. This is unfortunate in a medium that can rise to the level of art.

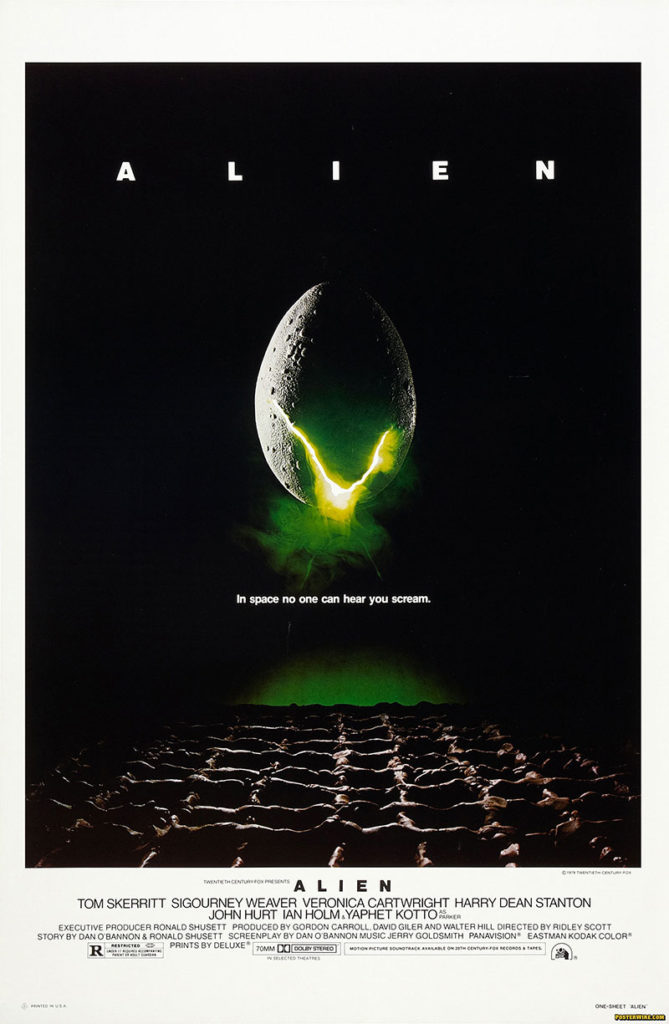

With that in mind, it is worth revisiting the original Alien from 1979 — the movie that first brought cinema’s most fearsome seven-foot space insects to theatres.

Alien has a pace, interrupted by frightening moments when the title monster makes its appearances. Director Ridley Scott, directing his second film, showed that he knew how to create and use tension, his performers effectively portraying characters who have been blindsided by events that endanger their lives. Unlike later films in the series, all the characters in Alien have authenticity. There are no gun-toting space smugglers, gung ho marines, or reformed prison monks. Instead, there are the future equivalent of merchant seamen — working people — contracted to ship materials from point A to point B. Upon awakening from hibernation after a long voyage, they are excited to soon be home, before long learning they have been revived prematurely to investigate a signal of unknown origin. For most of them, that signal becomes the harbinger of their deaths, which they did not seek, expect, or prepare for.

Thrust into unfamiliar circumstances,  they all try to deal with peril as best they can, underestimating the alien’s ferocity, and making mistakes they, more often than not, have to pay for in blood. These are characters a viewer can relate to, despite the distance from us in time and plot. Their regular day-to-day routine has been destroyed, and they are trying desperately to cope.

they all try to deal with peril as best they can, underestimating the alien’s ferocity, and making mistakes they, more often than not, have to pay for in blood. These are characters a viewer can relate to, despite the distance from us in time and plot. Their regular day-to-day routine has been destroyed, and they are trying desperately to cope.

There is not a bad performance in the lot. Sigourney Weaver (Ripley), Tom Skerritt (Dallas), Yaphet Kotto (Parker), Harry Dean Stanton (Brett), Veronica Cartwright (Lambert), Ian Holm (Ash), and John Hurt (Kane) all appear comfortable in their roles and with each other, like a stage cast that has been together for an extended run. Nothing is forced, the light times are easy going, and when tragedy finally strikes, the stress is palpable. Cartwright’s Lambert succumbed to weepy hysteria at times, however. That was the only thing about her performance that could have been better served by a little less genuineness.

Good acting and frightening story reside in a film that is visually gorgeous. Ridley Scott has a talent for helming films that look stunning. Making the interior of a spaceship look appealing is a unique problem. Scott, cinematographer Derek Vanlint, and production designer Michael Seymour accomplish this by hiding deceptively vast spaces among all the pipes and wires, making it feel at times like Alien was filmed on location in an abandoned steel mill. This rust belt feel also keeps the environs of the ship grounded in reality. Too often the future is portrayed as a place where no dirt accumulates, no machinery shows wear and tear. A good share of grit mirrors nicely the authenticity of the characters.

Outside the ship, special effects artists Brian Johnson and Nick Allder created models and backdrop for an operatic sequence when the ship approaches an alien planet. Done before CGI, the visuals are as crisp and detailed as shots from the Hubble telescope. The use of real objects restrains camera angles to the realm of believability, unlike the rollercoaster ride of impossible shots from today’s more undisciplined computerized fare.

Finally, the Alien itself is grotesque and terrifying. The few times it is seen on screen are unsettling. Its appearance conveys powerlessness against it. To confront it means to die. A second set of thrusting fangs is overkill, but truth be told, they’re not about the teeth. H.R. Giger’s designs are now world famous. Much of this is due to Scott’s reluctance to reveal the alien onscreen. Of all the Alien films, this is the entry that creates the most fear, proving that anticipation can be better than payoff.

Addendum — 2003 saw a theatrical re-release of Alien as a director’s cut. This print added six minutes of footage from the cutting room floor. These extras don’t add anything to the film, and thankfully don’t hurt it, either. Both cuts are available commercially. One odd bit about the 2003 release: although it added old footage, new editing and compression has left it with a slightly shorter running time than the original.