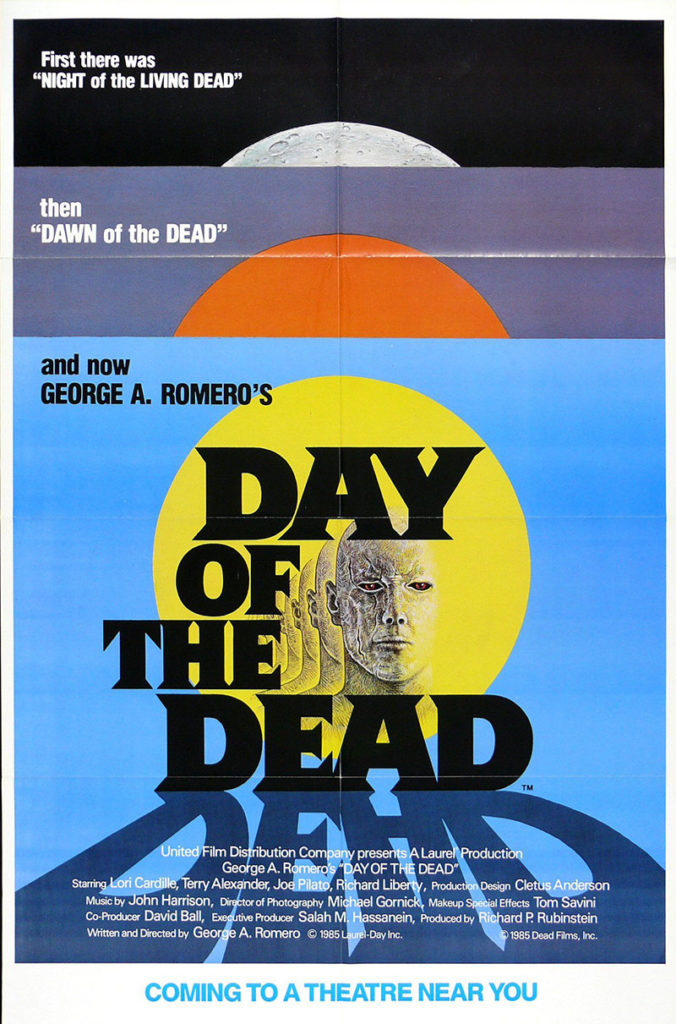

The zombie hordes have once again invaded the October Horrorshow here on Missile Test. After a short interlude that featured an amorphous blob, a ghostly pedophile, and a village full of children with psychic abilities, we return to the realm of the undead with George A. Romero’s second sequel to his groundbreaking film Night of the Living Dead, 1985’s Day of the Dead.

The zombie hordes have once again invaded the October Horrorshow here on Missile Test. After a short interlude that featured an amorphous blob, a ghostly pedophile, and a village full of children with psychic abilities, we return to the realm of the undead with George A. Romero’s second sequel to his groundbreaking film Night of the Living Dead, 1985’s Day of the Dead.

In this film, the survivors of the zombie apocalypse portrayed in the first two Romero films have been whittled down to a small handful of government scientists and soldiers living in an underground laboratory. Their remaining purposes in life have been reduced to scavenging the surface for supplies, searching in vain for other survivors, and researching the zombie condition, in an attempt to find a cure. The new order of things is open to interpretation among the group, as only the scientists have any interest in continuing the experiments. Their juvenile military protectors don’t seem to find any useful purpose in the scientists’ work, and increasingly assert their control over their egghead compatriots with threats and intimidations. Romero establishes the hostile attitudes these two groups hold for each other early on, and the viewer can be assured that this conflict can be even more dangerous than that presented by the undead.

The underground facility is, for the most part, secure and impregnable, but there are a small number of zombies locked away in a corral that make for a constant presence of danger. Inevitably, and predictably, it is these zombies that initiate the troubles that consume the residents of the lab.

The main human antagonisms are carried out between scientist Dr. Sarah Bowman (Lori Cardille), and the newly minted leader of the military contingent, Captain Rhodes (Joe Pilato, who also made a brief appearance in Dawn of the Dead as leader of a rogue group of police trying to flee the zombies). They spend a good deal of the movie dancing around each other until one of the scientists, Dr. Matthew Logan (Richard Liberty), crosses the line of decency by keeping a supposedly domesticated zombie in his lab. The scientists’ and soldiers’ mistrust for each other continues to grow, until the tenuous amount of tolerance the two groups have for each other collapses, leading to events that loose third act carnage. No surprises or spoilers here, there was no other outcome possible.

Romero’s aims in Day of the Dead seem to be twofold. First off, he seems to be concerned with the relationships formed between the armed and the intellectual individuals within a stressed environment. Are the live people in more danger from each other than they are from the undead? It’s a valid question that hangs over most of the movie. Next, Romero integrates the idea that zombies are still somewhat human, and could still be possessed of enough humanity to no longer be a threat. He hinted at this in Dawn of the Dead, showing the undead reverting to base learned behavior as they wander around a shopping mall, acting out what seem to be vestigial memories. This was more relevant as commentary on the state of American consumerism, but still laid the groundwork for the ideas he explored later.

In Day of the Dead, the experiment in training a zombie that is undertaken yields definite, although unreliable, results. Later, Romero expanded this theme of cognizant zombie behavior and decision making ability in Land of the Dead and Survival of the Dead, but it was in Day of the Dead that any sort of real human characteristics, or misguided anthropomorphism, was present in the undead.

Of course, much of the optimism turns out to be human folly, and that’s when the film descends into outright gore. And it’s an impressive amount.

Romero had a larger effects budget for Day of the Dead than he did for Night or Dawn, and it shows. Gone are the pale grey zombies of the previous film. Here they are replaced with masterpieces of 1980s horror makeup, courtesy of Tom Savini. These undead look like rotting corpses, putrid and disgusting, missing flesh in all the right places, and when they kill, their victims are torn apart in spectacular fashion.

Day of the Dead follows the two preceding films in that it is a one location flick, but like Dawn and Night, it occupies its own space, its own style, and owing to the distance marked by the passage of time in the real world, its own niche in cultural sensibilities. Unlike Dawn of the Dead, there are no absurdist or comical asides, yet unlike Night of the Living Dead, the tension falls flat. So while Day of the Dead is an important film in the zombie subgenre of horror, it’s the first in the Romero oeuvre that has more in common with b-movie fare than with groundbreaking horror cinema.