When I imagine Purgatory, I have a fairly concrete vision in mind. I’m standing on a New York City subway platform during the morning rush hour. It’s August. The heat is stifling, and I had a twenty-minute walk just to reach the station. By the time I find myself standing in the stagnant air, waiting for the next train, I’m pouring sweat. During the night, some bum defecated on the platform and its ripe smell has been added to the unique bouquet of rot and brake dust that gives the New York subway an odor all its own — truly something unique the world over.

The train is late, and by the time it arrives, the platform is full of people ready to get on and go to work. But they can’t. The train is totally full. When the doors open to let people on, there is no room for any new passengers. The people inside have dull eyes, almost grey and glazed over, like one would find upon peeling back the top of a can of sardines. And that’s what they are.

So far I have not described Purgatory, but rather any bad morning a commuter is likely to encounter during the morning rush hour in the Big Shitty. No, my vision of Purgatory begins when, after three or four more trains pass through the station, still with no room to take on more passengers, one finally arrives that has just enough room for me to squeeze in. I push and jostle my way aboard, actually wanting to be on this train for some reason. In fact, I desperately need to be aboard, otherwise I will continue to wait, and it will only take longer for me to get to my destination.

The train is packed so tightly I can barely move. Every person standing has one arm up holding on to the overhead bar for balance. On one side of me is a tall man wearing a sleeveless t-shirt, and when I turn to face him I can almost feel the hairs in his armpit tickle my face. He does not use deodorant (smell is going to be a continuing theme  here; if you’ve ever ridden the subway in New York, then you can understand why). To the other side is a young woman who is very pretty. I’m very attracted to her. Her purpose for being there is to remind me of my timidity and fear for the duration of the trip. I have to choose to be either tortured by the smell to my right, or the stupid fantasies that run rampant through my brain brought on by the woman to my left. In addition, the man standing behind me is wearing a backpack. Throughout the ride, it will be threatening to push me down on to the seat in front of me, which is occupied. Why doesn’t he just take off the backpack and rest it on the floor between his legs? I will never know.

here; if you’ve ever ridden the subway in New York, then you can understand why). To the other side is a young woman who is very pretty. I’m very attracted to her. Her purpose for being there is to remind me of my timidity and fear for the duration of the trip. I have to choose to be either tortured by the smell to my right, or the stupid fantasies that run rampant through my brain brought on by the woman to my left. In addition, the man standing behind me is wearing a backpack. Throughout the ride, it will be threatening to push me down on to the seat in front of me, which is occupied. Why doesn’t he just take off the backpack and rest it on the floor between his legs? I will never know.

All the seats on the train are occupied by demons. They boarded the train at its origin point. By the time it reached its first stop, all the seats had been taken, and the souls condemned to ride the Purgatorial Subway all have to stand. The demons take up more space than they should, either by spreading out their legs in the rebellious, inconsiderate teen fashion we all know, denying people seats, or because they placed their briefcases and bags next to them, letting everyone see that their material possessions deserve a seat more than any of us poor, doomed bastards.

Someone on the train is eating halal food with goat meat and onions so powerful that the smell is indistinguishable from the sweat of the person next me. Whoever that person is gets off at their destination and is replaced by someone eating steamed dumplings that smell like farts. This would be much worse for me if there already hadn’t been multiple times during the trip when someone passed gas. How can people stand to eat aboard a subway train? It’s like eating in a bathroom. No meal is so urgent that it can’t wait for outside air. Now we all have to suffer.

I look up at the lighted board listing all the stops on the route, and I see that my stop, where I get off and leave purgatory, is 10,100 stops away, plus 32. I don’t know what I did to deserve the extra 32 stops, but I’m sure by the time I get near there, I won’t care. Unfortunately, there are no express trains on the Purgatorial Subway, so progress is slow.

Over the course of the trip, various demons in the guise of beggars and musicians wander through the crowded car, begging for money. For the beggars, I’ve heard their sob stories a million times. They never change and it is clear that they find the captive audience, if not truly lucrative, then reason enough to keep coming back. One woman has been pregnant for over a decade, it seems. One man has been homeless and unemployed for the past six weeks, always the past six weeks, even as the years creep by. As for the musicians, they never, ever, ever, play any music that I do not hate with all my doomed soul, and they only appear in my car when a song that I like comes up on my iPod. Otherwise my iPod plays only bad songs from great bands.

Eventually, after time incalculable has gone by, and I near my destination, the train stops in the tunnel, seemingly for no reason. All announcements over the intercom explaining the delay are either garbled or too quiet to understand. Long ago someone has vomited in a corner, but it is not until I am close to my destination that it begins to bother me. More than anything I ever desired or wanted in life, I need to get off this train, and I begin to worry that by the time we reach my stop, I will be insane.

Finally the train begins to move once more. Six stops away. Five stops away. Four stops away, and that’s when I notice that the train did not stop for the last few stations. It skipped them. And I realize that because we were stuck in the tunnel for so long, train traffic behind us has begun to back up, and my train is now skipping stations to open up space on the tracks. The train finally stops and the doors open over a thousand stations past my destination, and I am forced to ascend to the street and walk back to my stop. It’s now pouring rain and I have no umbrella.

Oh, and the air conditioning on the car was broken.

So, my vision of Purgatory, then, is like any random rush hour subway ride, only longer. This is what I was thinking of as I watched Jan de Bont’s wretched remake of The Haunting.

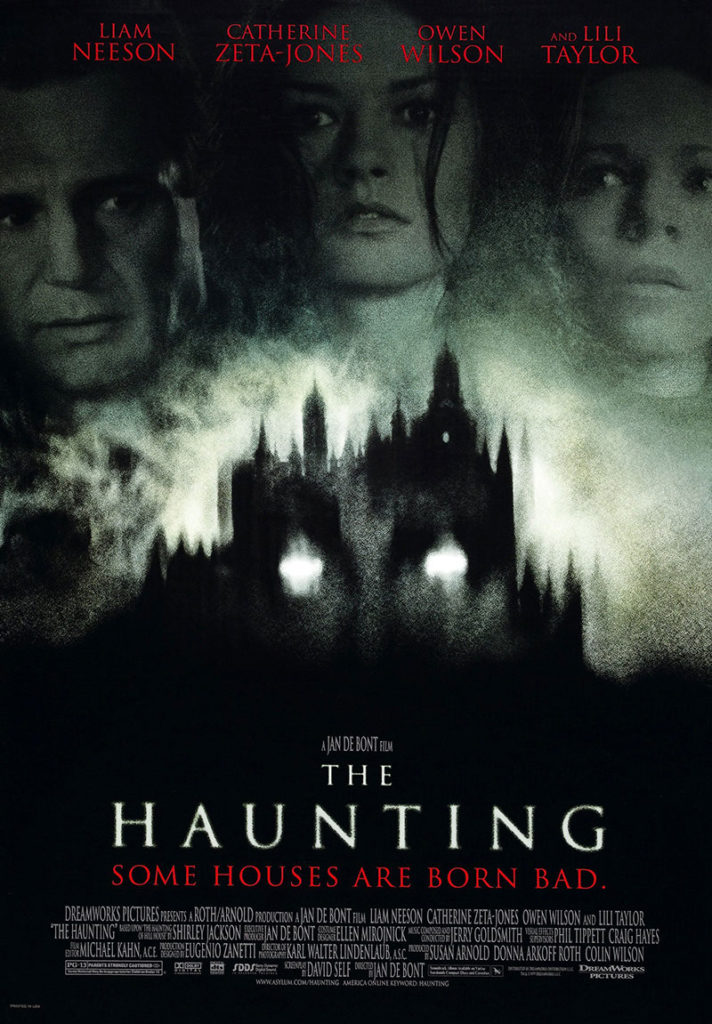

There’s an all-star cast in this one, including Liam Neeson, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Owen Wilson, but the star is Lili Taylor, in the lead as Eleanor.

The Haunting tells the story of a small group of people that arrive at Hill House, a stately pile long-abandoned that is the site of ghostly activity. In this film’s interpretation, only Liam Neeson’s character, Dr. Marrow, knows of the hauntings. He lured the others to the house under false pretenses, promising to cure their insomnia.

Hill House is a gaudy place, more a fever dream interpretation of baroque architecture than any real house (excepting the exteriors, which were not built on a set, but are indeed a real English country home). The gaudiness itself hints at the flaws plaguing this picture.

The biggest problem with the film isn’t that it’s poorly made. It’s that it is completely and totally overdone. Everything, from the settings, to the late ’90s era CGI, to Catherine Zeta-Jones, is so overwrought that the film becomes unengaging. There is no believability to the film. In fact, there is no way for viewers to even suspend disbelief and let themselves be taken along for a ride. It’s disconnected. This film is typical of Hollywood at its most obtuse. This is what they thought, and still think, people want to watch.

Robert Wise’s film from 1963 is one of my favorite films, regardless of genre. When I saw it the first time as a youngster, it scared the pants off me. I recently read the book it was based on, The Haunting of Hill House, by Shirley Jackson, and was impressed at the lilting and easy way she tells the story, while also being quite intense. In all interpretations, Jackson, Wise, and de Bont, the character of Eleanor is the central protagonist, locked in a dance with the house.

Eleanor had quite a lot of depth in Shirley Jackson’s novel and the original film. She’s a sympathetic character at first, a person to be pitied, in fact. As often happens with people you feel pity for, however, it doesn’t take long for those feelings to be superseded by contempt. It turns out Eleanor is a bit of a pain. So complex, so real, and so jettisoned by Mr. de Bont.

But then, all the things that made The Haunting work before de Bont got ahold of them have been jettisoned. Most importantly, this movie is a case study in why it is never a good idea to trade tension for spectacle in a movie.