It has begun! October is here. And with it comes the October Horrorshow here at Missile Test. All month long the site will be dedicated to horror film reviews. The good, the bad, the putrid — it doesn’t matter. As long as there’s blood, I’ll watch it. First up is some found footage.

It has begun! October is here. And with it comes the October Horrorshow here at Missile Test. All month long the site will be dedicated to horror film reviews. The good, the bad, the putrid — it doesn’t matter. As long as there’s blood, I’ll watch it. First up is some found footage.

Oh, no. Found footage? Again?! If I were emperor of the world, I would not ban found footage horror flicks outright, but I would require a special permit to make them. The only way to get such a permit would be through a personal interview with me. The only way to get a personal interview with me to discuss a found footage project would be to approach my palace as a supplicant...on hands and knees. From the moment prospective filmmakers land at the airport or arrive at the train station, or however they get into the city, they cannot be upright. They have to crawl all the way to my throne room. Then, as they grovel at my feet while addressing me using all my different names and titles, they must stretch out their left hand, so that my palace guard might lop off their pinky and present it to me as tribute. Then, and only then, will I even consider listening to a pitch for a found footage horror flick. But most important and most decisive, I think, for the filmmakers is this: if you make a found footage horror flick, I get gross points. I’m not Clooney. I’m not expecting 20 against 20, but there will be pain. Physical pain, emotional pain, fiduciary pain. These are the tolls I would exact from anyone looking to make a found footage horror flick. If they truly believe found footage is still the way to go after all that, then the filmmakers get my official imprimatur.

For about half the run time of As Above, So Below, the horror movie from directing/writing pair John Erick Dowdle and brother Drew, the found footage aspect is completely pointless. While watching, if a viewer can picture a found footage movie being filmed in a more traditional manner with no loss of narrative, and maybe even an improvement, then using found footage was a mistake.

The movie opens with the main character, Scarlett Marlowe (Perdita Weeks), entering Iran to explore a system of ancient tunnels that will soon be blown up by the Iranian government, thus burying all their secrets. Scarlett runs all around the tunnels with her little camera bouncing up and down, and all I could wonder was how this improved the story so much that it was worth ditching regular camera work. What benefit do we, as audience members, get from watching this film like some GoPro urbex footage on YouTube? Is it any more suspenseful? Does it add any more cohesion to the narrative? No. This early on, found footage adds nothing to this film, and things stay that way for most of the runtime.

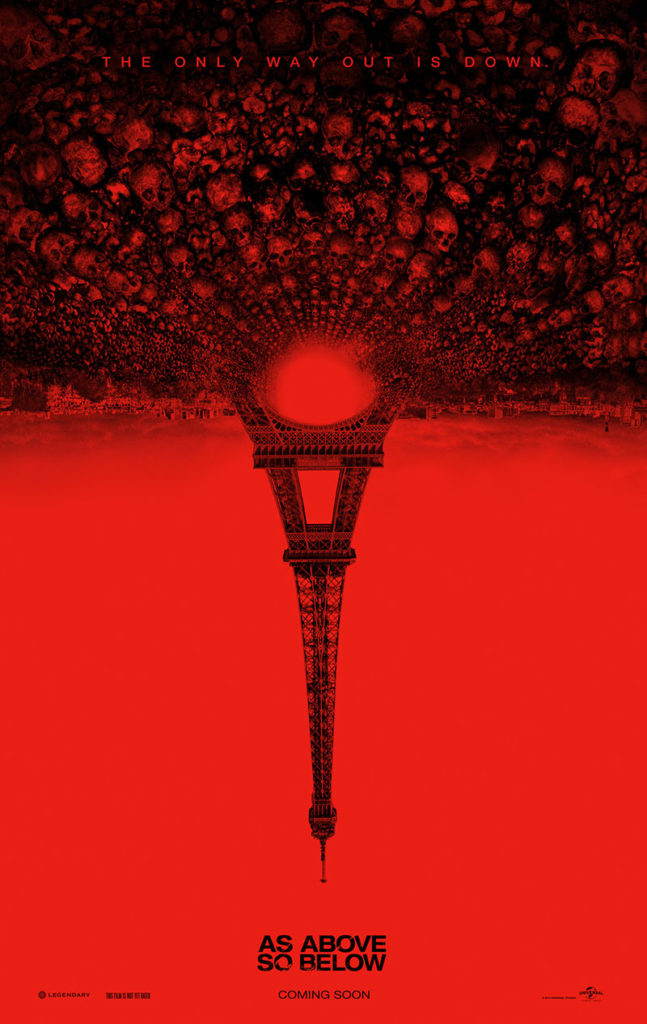

The scenes in Iran are introductory. The setting shifts to Paris and that is where the action starts. Scarlett is a scholar of alchemy searching for the philosopher’s stone, the mystical alchemical substance that is said to change lead into gold and grant immortality to its users. It turns out the stone might be in a long forgotten section of the Paris Catacombs. Scarlett enlists the help of the normal cast of characters one expects in a horror flick. There’s the ex who could turn out to be a rekindled love interest, George (Ben Feldman); the tough local guide, Papillon (Francois Civil); a couple others whose presence seems to be to fill out the cast; and, of course, the cameraman, Benji (Edwin Hodge). They all descend into the tunnels underneath Paris, and that is when things begin to go wrong.

Filmed in the actual Catacombs, the darkened tunnels and blind corners offered a real bounty to Dowdle and company. The atmosphere is ready-made and claustrophobic — oppressive, even. For someone like myself, who has a real fascination with tunnels and abandoned spaces, the idea that something evil may be lurking around the Catacombs is intriguing, as I think it may be for a number of people.

Other films have used similar settings. Some have even used the Catacombs, as well. But these films tend to be monster flicks, where unwitting explorers of the depths find some human/animal crossbreeds or devolved humanoid monsters with a hankering for flesh. There isn’t any of that, here. The Catacombs in this film are more possessed by demons than anything else. There is even a possibility that the entrance to the Christian hell is to be found along our adventurers’ path. The deeper they go into the tunnels, the more it appears they may end up finding the underworld. All of this does relate to the philosophers’ stone, believe it or not. In the story the Dowdles tell, hell and alchemy are interrelated. Seek one and the other will also be found.

The Catacombs are a wonderful filming location. Every single character in the film is wearing a headlamp, yet the light never seems to penetrate more than a few feet. John Erick Dowdle also deserves credit for preventing his film from becoming just a bunch of set piece scares with little going on in between. By the final act of the film, it began to feel like his poor characters were going to be stuck in the tunnels forever. And I do mean forever. Not that they would end up lost and starving to death, but that in exploring the tunnels, they have indeed entered a realm of punishment where their souls are forfeit for eternity. Dying would be no salvation. As the characters continued descending, I found myself keeping mental track of how far away from the streets above they were. Being aware of that distance became a form of currency in the film, adding to the tension.

There is nothing evil about a tunnel or an underground chamber. They are just musty-smelling places with no windows and walls thick enough to prevent any outside sound. They are atypical of the way humans experience their day to day lives, and that is what makes them inherently uneasy places. Dowdle used the location in this film to effect, realizing that making the tunnels the malevolent presence, and not some monsters creeping about therein, would make for better scares. There are some things that show up here and there, but throughout, it is the tunnels, the idea that they may be the corridors of hell, that works best.

As for the found footage, it makes more sense after the characters enter the Catacombs, but it still isn’t needed all that much until the characters realize how much trouble they are in. Also, by mounting the cameras on the actors as they mingle with one another, the shots convey the closeness of the walls in a way that a camera that had been pulled back could not. We, as viewers, always have the perspective of the pursued. Like walking through a funhouse, we have no clue what could be around the next corner. Or worse, what’s behind us. In the second half of this film, the found footage makes sense because it brings the viewer into the movie. It creates the illusion of participation. That is proper use of found footage. It’s too bad that Dowdle wasn’t able to make this work throughout.

As Above, So Below is not all that memorable of a horror flick. It hits a lot of the standard notes, but it has strong ideas behind the plot. By the end, I found that I was actually concerned with the fate of the protagonists. By this time I’ve seen so many horror movies that a lot of the time I just want the bad guys to get it over with so I can go to sleep. Not here. My goodness, I think I may have liked this little movie.