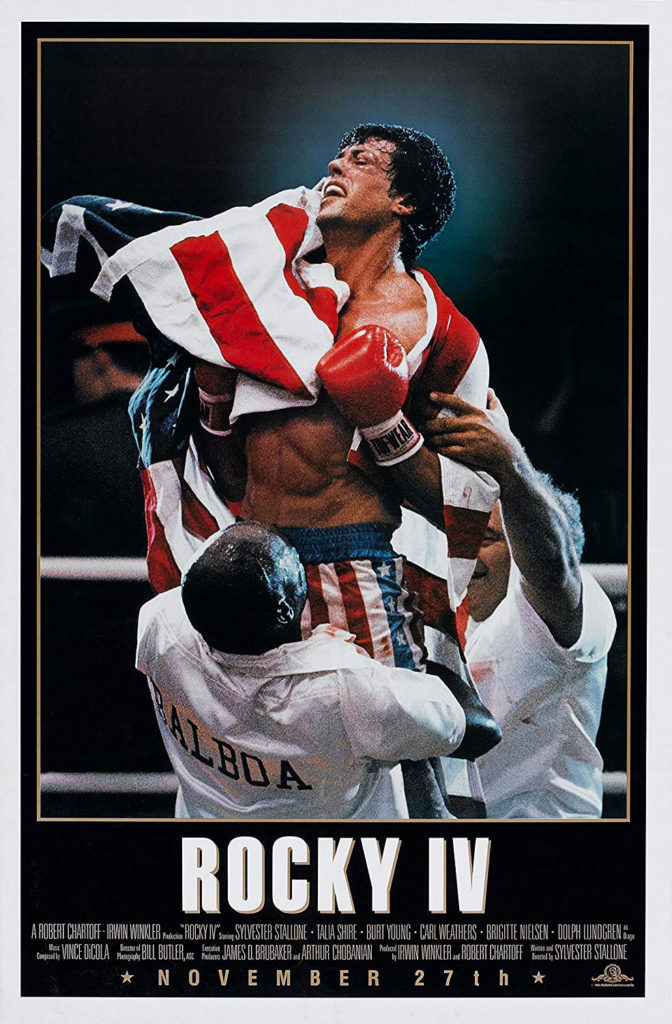

This film is, without a doubt, peak Rocky. Gone is the working class Joe with the wicked left. In his place is a warrior for not just the American way, but for the Reagan era. It’s a stunning character transition, and also makes for spectacle of the highest order. Just sit back and say “wow” whenever it feels appropriate. But first, viewers must endure Paulie’s birthday party scene.

Rocky IV was released in 1985. Besides returning to play the titular character, Sylvester Stallone also wrote and directed. This, for Sly, was complete creative control. He could take the character of Rocky wherever he wanted, and if that meant a jingoistic propaganda piece, then so be it. Temperamentally, Rocky IV may be a departure, but the overarching themes aren’t all that different.

Sly’s political beliefs started creeping into his films as soon as he found it possible. Sly is a self-made man and a conservative. He has encountered doubt and adversity, and perseverance was critical to his success. He should be, and has been, applauded for his achievements. But he, like so many other successful people, sees no reason why that success cannot be emulated by others if they just worked as hard as he did. Because so many others can’t do what he did, they must have some moral weakness preventing them from succeeding. They are unworthy of either riches or, perversely, help. Should they slip into poverty or destitution, no help should be forthcoming, because no one owes anybody a damn thing. The very idea of the public good is anathema.  Sentiments like these are all over Sly films from the ’80s. Sometimes it’s just a line or two, but the message is always clear. Sly was a man at home in the Reagan years. It is no surprise, at all, that he would take his most personal character and turn him into a warrior for the United States.

Sentiments like these are all over Sly films from the ’80s. Sometimes it’s just a line or two, but the message is always clear. Sly was a man at home in the Reagan years. It is no surprise, at all, that he would take his most personal character and turn him into a warrior for the United States.

In Rocky IV, both Rocky and Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers) are basking in retirement. Mansions, cars, and swimming pools abound. But, there comes an announcement that the world amateur boxing champion, a Soviet by the name of Ivan Drago (Dolph Lundgren, in his most famous role), is coming to the States to embark on a career in professional boxing.

The decision isn’t his. Drago is a propaganda piece for the USSR (much like this film was for us, in a funny way). He’s accompanied by a coterie of Soviet scientists and officials, including his wife, Ludmilla (Brigitte Nielsen), and his comically evil manager, Nicolai (Ohio’s own Michael Pataki).

Drago is a roided-up Soviet boogey man. In 1985, he fit right in with the raised tensions of the latter days of the Cold War. I remember those days, even though I was only nine years old when this film was released. By that time, we had spent decades in a standoff with the Soviets, and President Reagan introduced uncertainty into the equation, upending the ideas of parity and containment. All of a sudden, nuclear apocalypse was closer than it had been since the ’60s.

The Soviet man is represented in Ivan Drago. He is bigger, taller, stronger, faster, than our best. He has at his back the entire engine of communism. Drago is also a fraud, as he receives PED injections to aid in his training. The evil machine of communism has focused its efforts on this boxer, this lone representative of an inherently illegitimate political system, and they still have to cheat. At no point, ever, are these commies portrayed with any human characteristics beyond oppression. It’s a wild ride, this vision of our greatest foe.

Apollo, being appreciative of the opportunities he was afforded by being an American, is offended by the idea of Drago, and agrees to a fight. The fight is a brutal display, and Apollo is killed in the ring. It’s a devastating blow to both Rocky and the country. An ambassador of the might of the Soviet Union came to this soil for single combat and beat our champion so badly within six minutes that he died. In ages past, this would have meant losing vast swathes of territory. Luckily for us, in this age, all it meant was that another champion, Rocky, would want revenge.

The main thing I like about this first act of the film is that it focused on Apollo. He was always a complex character. He didn’t rival the importance of Rocky, but being an amalgamation of Muhammad Ali and the black experience in America, there was always so much more lurking behind Apollo than Rocky. It was nice seeing Apollo get his due, somewhat, in this film. Too bad he had to die.

The remainder of the film returns to the normal rhythm of a Rocky film. There will be a fight. Rocky and his opponent must train for that fight. That training is presented to the audience in montage form. Then follows fight, roll credits. It’s a predictable formula, sure, but if someone could think of another way to end a Rocky film, I’m sure it would have been filmed by now.

This film stakes out its own place in the franchise by making the fight about America versus the Soviets. Rocky III was about Rocky confronting his own doubts, but there’s no personal message in this flick. The American way is at stake. The weight of the propaganda is overwhelming. Yet despite that, it’s easy to get lost in this film. There is no ambiguity anywhere to be found. Not only is the world black and white, so are the values of the two combatants. On one side is the product of a monolithic machine of oppression. On the other, an American with talent and a work ethic. This wasn’t about Rocky and it wasn’t about avenging Creed. This was about the Cold War.

To be clear, the Soviet Union can go to hell. It’s a good thing that state is on the dustbin of history. Good riddance. But this flick is absolutely shameless. It’s also a hoot, like seeing the fireworks on the 4th of July. Sometimes, a little flag waving isn’t all that bad. I have no clue how this film plays across the border, but it wasn’t made for anybody but us Americans.