I didn’t think I was going to like this silly movie. If not for this month of reviews, I doubt I would have seen it again, ever. Demolition Man feels like a pure expression of movie by committee. The action genre had had much of its life polished out of it by the time this flick came around in 1993. The effect on this film is that, bizarrely, it feels as much like a stage play at times as it does a movie. There is no possibility for suspension of disbelief, nor does the movie require it for the viewer to be entertained. The ideas behind the film are outlandish, something of which the filmmakers were aware. Therefore they wisely shied away from heavy-handed seriousness in favor of the absurd.

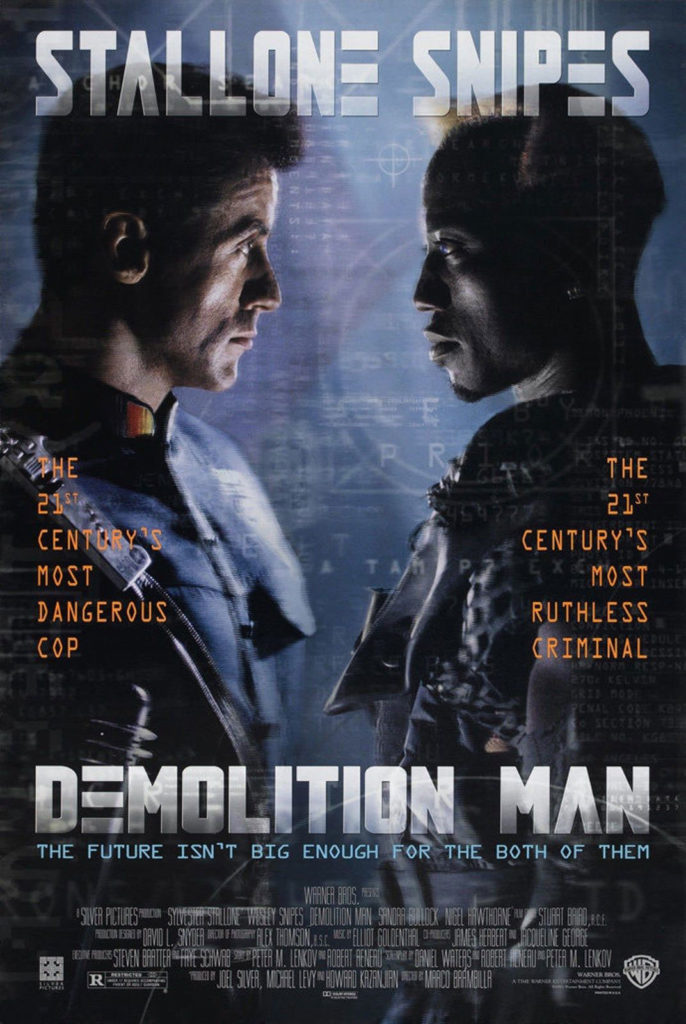

Directed by Marco Brambilla, Demolition Man follows LAPD Sergeant John Spartan (Sylvester Stallone) as he battles against criminal nemesis Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) in the not-too-distant year of 1996. It’s amazing how far Brambilla and company picture Los Angeles falling in the three short years from release to when the opening scenes occur. The film opens with a shot of the Hollywood sign burning. Much of the city appears to be a war zone, with lots of fires and explosions greeting the viewer. Back in the days before crime rates took a nosedive in this country it was a fairly common theme in film to see near future America overcome by violence.

Brambilla doesn’t waste any time getting the two stars together. There’s gunplay galore, some hand-to-hand fighting, and then one of the most gigantic explosions I’ve ever seen in an action film. The scale of the fireball (all practical effects, by the way) is astounding. It’s exactly what one would want from an action flick, but I remember back when this film came out that an explosion of this scale felt  somewhat obscene, like the genre had lost its direction and this was the best it could offer. For shame, 17-year-old me. 40-year-old me thinks that big boom was awesome.

somewhat obscene, like the genre had lost its direction and this was the best it could offer. For shame, 17-year-old me. 40-year-old me thinks that big boom was awesome.

Spartan gets blamed for the explosion and the lives it took, although he was responsible for neither, and gets sentenced to a long term in cryogenic freeze alongside Phoenix. And this is where the film really takes off, because 1996 isn’t nearly far enough in the future. We are off to the year 2032!

That’s the year that Simon Phoenix is awoken from his suspension for a parole hearing. Wait. Parole? How does that work?

In this film, cryogenic freeze is a humane way to send someone to prison, but it’s not a passive confinement. While the prisoner is in suspension, he is subject to synaptic stimulation and reprogramming in order to remove criminal tendencies. The parole hearings, I gather, are when the techs at the prison wake someone up to see if the reprogramming worked. In the case of Phoenix, it did not (or did it?), and he breaks free into a future SoCal that is so peaceful there hasn’t been a murder in 22 years.

The film’s portrayal of the future society is absolutely precious. Everyone is super nice to each other. The streets are clean. Everyone is prohibited from engaging in harmful behavior yet seem completely fine living within such a strict rule set. There are so many implications this society has for a viewer who is politically minded, like myself. Is it the ultimate expression of fascism or liberalism? Taken to their extremes, all political ideologies eventually become oppression, but the people of this future society seem so happy. What to make of it all? Well, maybe since the film is from 1993, when the current political polarization was but a gleam in Newt Gingrich’s eye, I should stop reading so deeply into it. After all, this flick is about Stallone and Snipes kicking ass, not some commentary on political morality.

But, this future society has turned everyone, and I mean everyone, into total pussies. Their happy little contentment means they are incapable of capturing the rampaging Phoenix. But one cop, the bubbly Lenina Huxley (Sandra Bullock) comes up with a plan. In order to stop a 20th century criminal, one needs a 20th century cop. Therefore, Spartan is defrosted, reinstated to the police force, and partnered up with Huxley to chase down and stop Phoenix.

That part of the plot is standard action fare, with some spectacle thrown in that takes it out of the range of believability, as I wrote about above. But the true meat of this film is Spartan’s fish out of water story. His reactions to the world around him, and the film’s light embrace of the absurd, are what make it work, more than the action. Sure, a whole pile of the jokes in this flick fall flat, but there is so much rich fodder in the environment Brambilla crafted. A more deft hand behind the camera could have gotten more out of the excellent ideas behind the film, but just because it did not reach its full potential is no reason to cast Demolition Man away. There’s some creative stuff going on here.

Demolition Man came around when ’80s action stars, and the genre itself, was struggling for relevancy. Back then, these films were castigated for failing to live up to the peak standards of the genre from only a few years before. But there is still a load of fun to be had in films like Demolition Man.