It has been over a hundred and twenty years since Bram Stoker’s groundbreaking vampire novel was published. In that time, the titular character of Dracula has been put to film dozens of times. Every generation gets its own version of the tale. There’s just something about Dracula. The genre of horror itself is drawn to the character like one of his hapless victims. One can be sure that no matter what kind of just fate befalls Dracula in these films, it is only a matter of time before he returns.

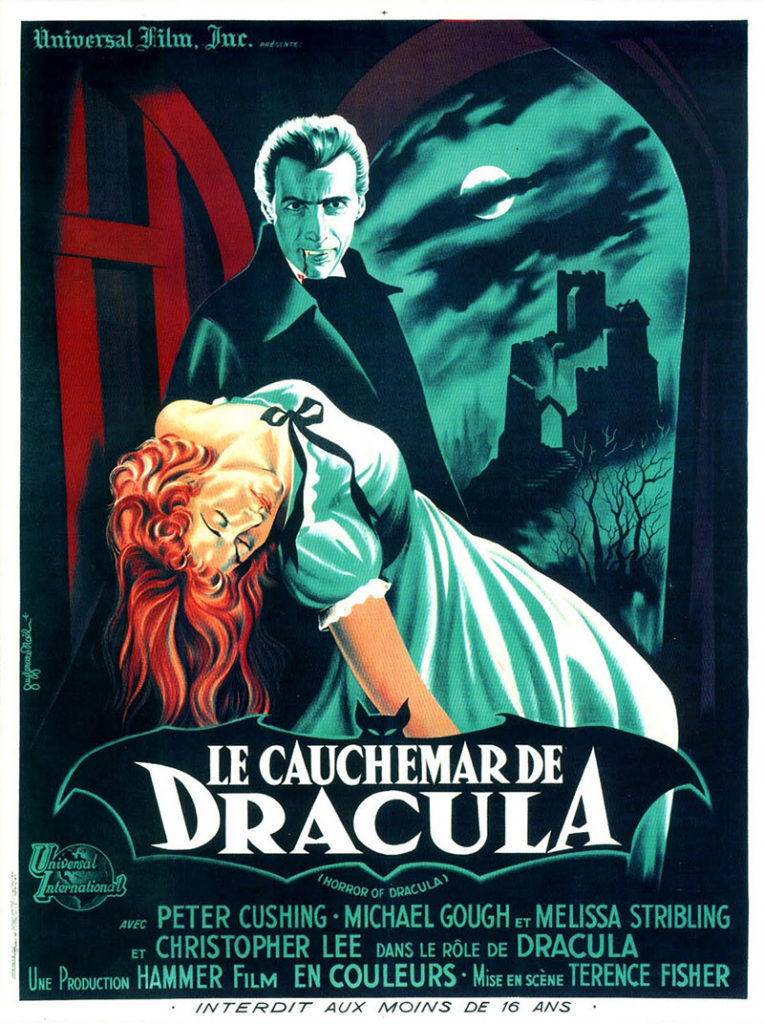

Dracula, released in the United States as Horror of Dracula, was Hammer’s first entry into the long list of Dracula adaptations. Released 27 years after the first of the Universal Dracula films, part of the purpose of this film must have been to take a character that Universal had turned into camp and reground it. There is always a good Dracula tale waiting for a filmmaker or two to come along and offer a reinterpretation. For a company that was still dipping its toes in horror, Dracula must have looked like low-hanging fruit to Hammer Film Productions. It comes with a readymade and malleable plot, and built-in familiarity with the moviegoing public.

The film was directed by Terence Fisher from a screenplay by Jimmy Sangster. Really, by the end of this month, it will look like I’ve copy/pasted that last sentence into most of the reviews. Fisher and Sangster are at the heart of so many of these Hammer films. Here’s another: The film stars Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee.

Cushing plays the vigilant vampire hunter Van Helsing, while Lee, of course, plays Dracula. He plays Dracula as somewhat of an English gentleman, excising the Eastern European foreignness that added to Dracula’s creepiness. It’s not a baffling decision, but it does serve to remove much of the distance between the demonic Dracula and regular people. That valley between the two was very useful in enhancing Dracula’s evil nature.

Dracula is Lee’s signature role. He had a wonderful career as an actor, appearing in over 200 films over the course of eight decades. Dracula is not the albatross around his neck that it  was for Bela Lugosi, mostly, I think, because Lee was a much more talented actor. His abilities and profligacy meant that, although one can associate him with this single character of Dracula, it cannot be used as the sole measure of his career.

was for Bela Lugosi, mostly, I think, because Lee was a much more talented actor. His abilities and profligacy meant that, although one can associate him with this single character of Dracula, it cannot be used as the sole measure of his career.

Dracula is a quite condensed version of the source material. Gone are Dr. Seward, Renfield, Quincey Morris, and most of Dracula’s brides. They were ruthlessly chopped from the story. The result is a lean telling that clocks in at just 82 minutes. I applaud Fisher and Sangster for their efficiency, but damn.

I don’t know enough about Hammer’s history to know why they chose to trim so much, but it might have something to do with the budget. It’s hard to look back at a year as distant as 1958 and make sense out of the purchasing power of pounds and dollars at the time. But for comparison’s sake, South Pacific, the top-grossing American film that year, had a budget of around $6 million, while Dracula was made for £81,000, or about $98,000 at the exchange rate of the time. Talented filmmakers do not need a substantial budget to make a good movie, but it sure helps. Perhaps another ten thousand pounds would have made all the difference to Hammer, and they could have fleshed out the production some, although the film does just fine as is.

Dracula begins, of course, with Jonathan Harker (John Van Eyssen) arriving at Dracula’s castle. Unlike in the source material, Harker’s visit is not an innocent one. He is aware ahead of time that Dracula is a creature of the night, and has plans to rid the world of his evil. He doesn’t succeed, which leads to Van Helsing arriving on scene. Van Helsing has dedicated his life to hunting vampires, and although he arrives too late to help Harker, he remains on Dracula’s tail as he flees his castle.

Dracula makes his way to Harker’s hometown, as he always does. Only in this film England is nowhere to be seen. Harker and Lucy Holmwood (Carol Marsh), his betrothed, hail from much nearer the Carpathians than in the source material. Again, this appears to have been in the service of condensing the story. Lucy is being visited in the night by Dracula. His feeding is causing a wasting illness that her brother, Arthur (Michael Gough), and his wife, Mina (Melissa Stribling), are helpless to ease. Van Helsing’s investigations lead him to the Holmwoods, and he teams with Arthur to battle Dracula.

This Dracula is a swift film. The condensing I mentioned above is very noticeable to viewers familiar with either the novel or one of the many other adaptations. Taken alone, there are no ill effects on the quality of the film. But at times it does feel like the film is only paying lip service to the source material, as if there is required material that must be gotten out of the way before the film can move forward. That doesn’t stop this from being an essential part of the Hammer filmography, however. Dracula was Hammer’s bread and butter, and it’s easy to see why.