Horror films are more than just about fear. They run the gamut of distressing emotions. Besides fear there is its more frantic cousin, panic. There is also disgust, grief, loneliness, and, of course, dread. Going beyond fear into these other realms of negative emotional experience can do a lot to rob the fun from a horror flick, but they also introduce realism and honesty into stories that, otherwise, have little more depth than a carnival funhouse. Today’s film dips far into a reservoir of hopelessness, so much so that the experience will linger in a viewer’s mind after the credits roll.

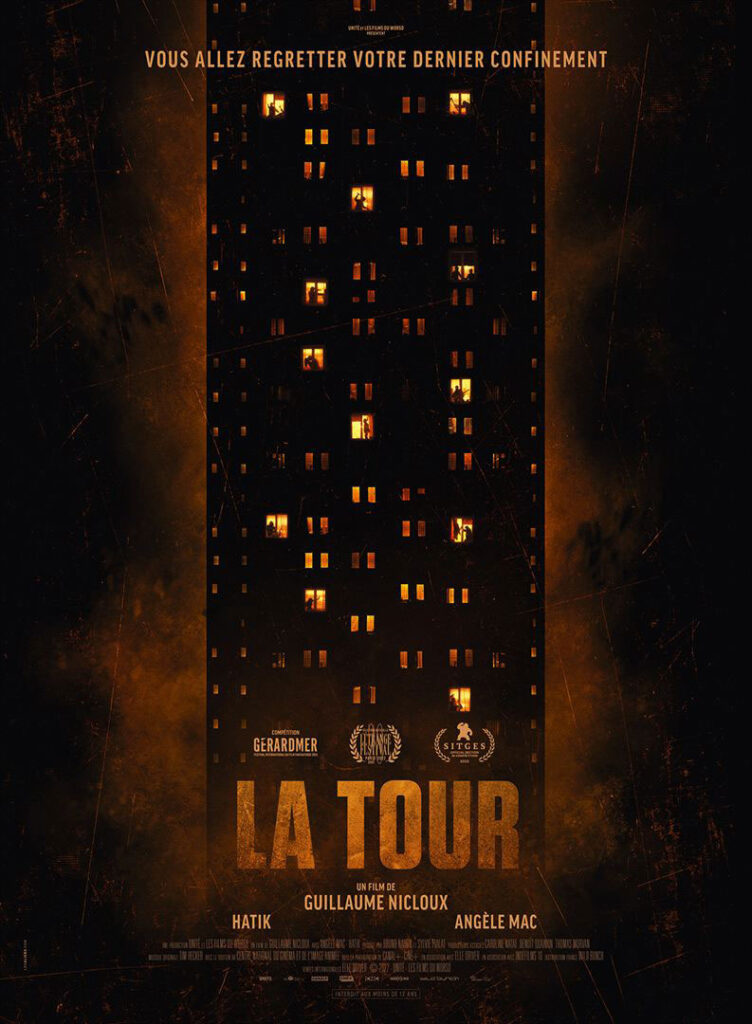

From France comes Lockdown Tower, a bastardized version of its original title, La tour (translated as The Tower), meant to evoke what we all went through during the Covid lockdowns of a few years back. Such an unequivocal title is unnecessary. We were all there. And it evokes an agency of distress that is far different from what is seen in the film.

Written and directed by Guillaume Nicloux, Lockdown Tower takes place at an urban tower block in France. The building is a diverse place, where caucasians live alongside Blacks and ethnic North Africans. One morning the residents of the tower discover that an inky shroud has descended around the building. They can no longer see anything beyond the windows and exits of the tower. Anything that passes through the shroud disappears, and things that only partially pass are neatly severed at the point of contact, to injurious result.

By the end of the first day the residents of the tower are consolidating into factions based on race. The racial tensions afflicting France are known outside of that country in broad strokes, but foreign viewers, such as myself, will be aware they are missing  much of the nuances involved. Shorthand for viewers here in the States is that the new situation resembles a prison flick.

much of the nuances involved. Shorthand for viewers here in the States is that the new situation resembles a prison flick.

As time goes on, the divisions between the residents harden. Trust is lost. A state not unlike simmering gang war prevails. Meanwhile, everyone in the tower has to figure out how to survive without any contact with the outside world. There’s a good chance, indeed, that the outside world no longer exists.

Here is where the film requires suspension of disbelief from the viewer in order for the plot to move forward. There is no way out of the tower, and no way in. Everything that passes through the shroud is literally cut off from everything which remains. How, then, is the power still on? Why did power remain yet water is cut off? Most unrealistically, the tower is now a closed system, with the exception of the electricity, yet the residents can grow tubers and breed housepets as livestock. This is one of those times when it’s best to not think too hard while watching. The logistics of the film are not the point.

Lockdown Tower is all about the battle against isolation and, as the movie goes on, total and abject despair. The film takes place over a longer timeframe than one might expect, and as time passes, and also because this movie is French, it becomes clear that a happy ending will not be had.

Of the twenty-three directing credits Nicloux has on IMDb, as of this writing, Lockdown Tower is his lowest rated since 2006. This film was not well-received, and I think that’s because of how unpleasant is the emotional experience of watching the story unfold. At least one critic, and plenty of viewers, latched on to the unrealistic nature of surviving in the tower as a kind of surrogate for how effectively Nicloux manipulates the audience’s emotions. They did not like how Nicloux made them feel, so lashing out at and magnifying the flaws of the film is therapeutic.

I, for one, was rapt. By the end of this film’s 89-minute running time, the aching pit in my stomach had grown from pea-sized to a cantaloupe-sized black hole of despair. The film moves from light to dark, from confusion to oppressiveness, at a steady and relentless rate. There is no uplifting message, and there is no reprieve. A movie like this is not for everyone. I’m glad that most horror movies are fun. I’m also glad that, on occasion, a filmmaker chooses to explore emotions that are deeply uncomfortable.