Mix one part huge spaceship, one part small cast, and one part gore, blend on high, and what do you get? Alien. Or one of the many Alien clones that have dotted sci-fi cinema for the last thirty years. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. Formulas in film that work well are often repeated ad nauseam, and while they never quite live up to the creative spirit at work in the original, they still serve to entertain, and that is the primary purpose of film. Even Alien itself is derivative of earlier films, most notably It! The Terror from Beyond Space, including many, many other sci-fi and horror films that portray a small group of people being mercilessly slaughtered one by one. But these days, where there’s outer space and buckets of blood, there is a debt of gratitude owed to Ridley Scott and his crew from 1979.

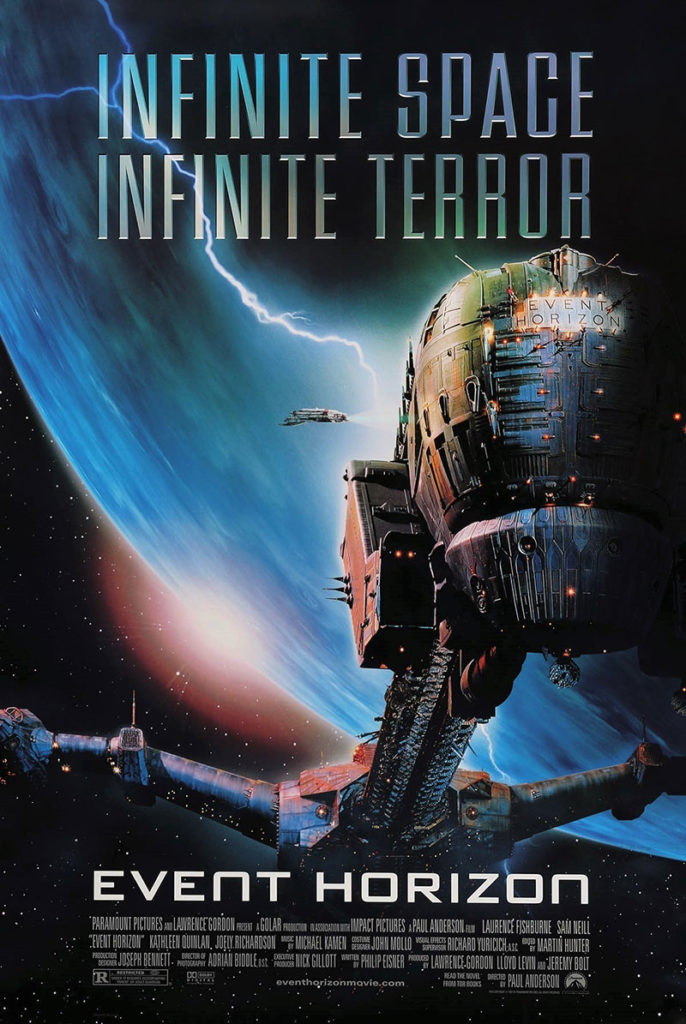

Event Horizon, from director Paul W.S. Anderson, can be saddled with Alien clone designation, despite there being no ravenous monster at work in the plot. Rather, a malevolent presence that may or may not be the devil has turned a derelict spacecraft into what has been referred to as a “haunted house in space.”

The idea behind the film is promising. In the near future, a spaceship, the Event Horizon, has been lost while testing a new engine that would allow instantaneous travel between the stars, the holy grail of space exploration. Years later, the ship mysteriously reappears in orbit around Neptune, and a small rescue ship is sent out from Earth to investigate and save any surviving crew.

The rescue ship, the Lewis and Clark, is commanded by Captain Miller (Laurence Fishburne). His crew displays the generic diversity common in films of this sort, including the resident know-it-all, Doctor Weir (Sam Neill), a temporary member of the crew, along for the ride because he is the designer of the Event Horizon.

Upon arriving at Neptune, the crew of the Lewis and Clark locate the Event Horizon, and the movie begins in earnest when that ship is boarded. The Event Horizon is completely derelict, it’s crew scattered in bloody pieces throughout the forward section. The mystery of the ship’s fate now includes why and how the crew was slaughtered, alongside the circumstances of its disappearance. Anderson establishes  early on that the very engine of the ship may have something to do with the goings on aboard her. Strange happenings begin to manifest aboard the Event Horizon while the rescuers are aboard, eventually leading to the demise of much of Miller’s hands. By the end, only a few of the initially small cast has survived to bring about resolution to the story. That makes Event Horizon not only an Alien clone, but a film utilizing the classic SCREWED formula.

early on that the very engine of the ship may have something to do with the goings on aboard her. Strange happenings begin to manifest aboard the Event Horizon while the rescuers are aboard, eventually leading to the demise of much of Miller’s hands. By the end, only a few of the initially small cast has survived to bring about resolution to the story. That makes Event Horizon not only an Alien clone, but a film utilizing the classic SCREWED formula.

Event Horizon touches lightly on concepts inherent to many branches of theoretical physics, metaphysics, spirituality, cross-dimensionality, and group psychosis, but never settles on any one source for the horrific goings on aboard the ship. All that is mere backdrop to a film that has fine production design, but is pedestrian when it comes to both story and scares. It’s not that such high-handed material had to be dumbed down to be attractive to a larger audience. Compare Event Horizon with a sci-fi film such as Sunshine, and one sees that even an intelligent film can compete on equal terms at the box office (both films were mediocre performers). That being the case, erring on the side of intelligence should be the preferred means to producing a sci-fi/horror film.

As stated earlier, Anderson didn’t skimp when it came to the film’s look. This has been a constant throughout most of his work, with rare exceptions. His bad films tend to look good. The CGI is vintage 1997, which makes it look dated today, only twelve short years later, but it was state of the art in its time. Some of the interior sets are striking, especially the green-lit shaftways surounding the Event Horizon’s engine room (itself among the highlights of the sets). The scenes where they are used are evocative of Alien, once again, but instead of being dark and foreboding, as they were in Alien, these shaftways are overlit, the bright green creating a disturbing mood similar to the pale walls and bright fixtures of a hospital examination room. Even before anything happens, they are uncomfortable places to share with the characters on the screen.

Event Horizon, though, just isn’t that good of a film. There aren’t enough surprises to keep a viewer engaged in the plot, and the characters and dialogue were both pulled from the Hollywood Studios’ ultimate book of cliché. Good ideas poorly executed litter the bargain bins of DVD stores throughout the world, and pollute the overnight airwaves of television stations. Event Horizon belongs among their number. Still, it’s better than Alien: Resurrection, which, strangely enough, feels more akin to Event Horizon than it does to the original Alien. The amount of circular logic set off by that idea is mind-boggling.