It’s October once again. The leaves are changing, the humidity is low, and the air is full of the smell of blood. That’s right, October is the month of Halloween, and also when film buffs the world over celebrate the greatest genre of film — horror. Missile Test has joined in the celebration, dedicating the entire month of October to watching and reviewing horror films. The good. The bad. The putrid. There’s no rhyme or reason here. If it bleeds, it leads.

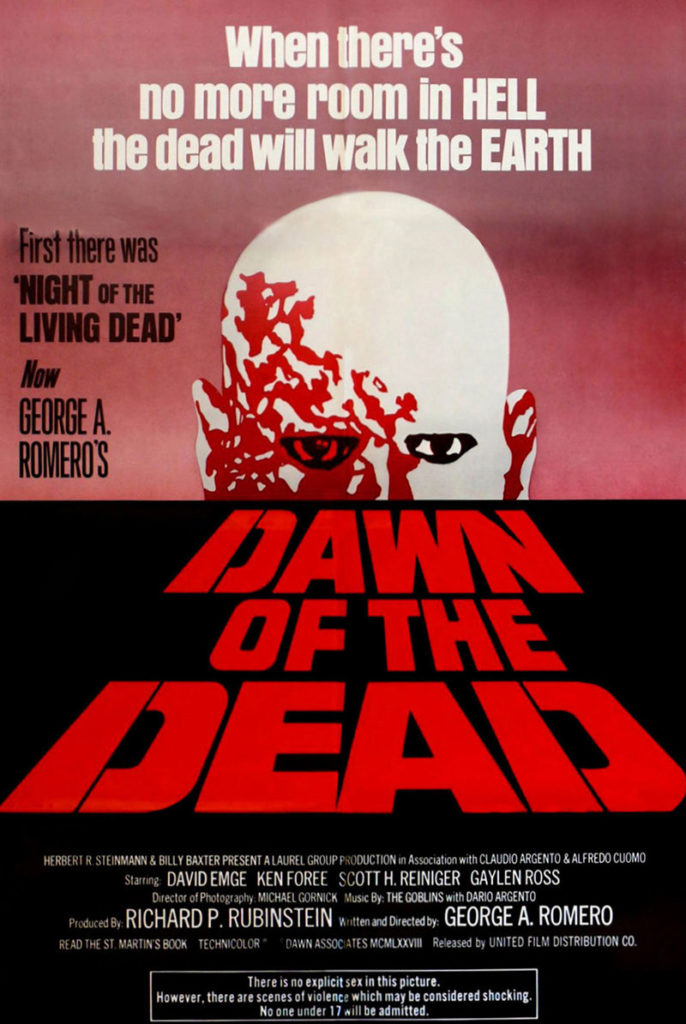

Horror auteur George A. Romero waited ten years to make a sequel to his groundbreaking zombie flick, Night of the Living Dead. What he made is not a film as revolutionary as what came before, but is still a classic of horror cinema.

Dawn of the Dead begins during the initial outbreak of the zombie plague, while government and society are trying to cope, and before the hopelessness sets in. There is a scene early on where members of the local SWAT team assault an apartment building where local residents have harbored their zombified relatives, morally conflicted as to whether or not these people can be disposed of so readily, so shamelessly, without consequences to their souls. It’s a weighty and powerful part to the film, showcasing the desperate early efforts of an overwhelmed government to deal with this supernatural menace. It also points out, earlier than most zombie films do, that the undead at least used to be people. They do not deserve our sympathy or compassion any longer, but that is the view of logic and reason. When a person watches a loved one turn into a flesh-eating monster, maybe rational thought is superseded by emotion, despite the obvious danger.

The protagonists flee the big city in a helicopter and observe from above the lighthearted efforts of the local hilljacks to control the outbreak, echoing the ending of the first film. But that ending could lead one to believe that eventually the authorities were able  to get a handle on the zombie plague. Dawn of the Dead shows that these efforts to combat the horde were in vain. Society is indeed gone. Collapsed. And the only responsibility a person has is to themselves, and any person that can help them survive.

to get a handle on the zombie plague. Dawn of the Dead shows that these efforts to combat the horde were in vain. Society is indeed gone. Collapsed. And the only responsibility a person has is to themselves, and any person that can help them survive.

There are only four protagonists in the film. Stephen, Peter, Roger, and Francine, played by David Emge, Ken Foree (the standout performer), Scott H. Reiniger, and Gaylen Ross, respectively. They eventually find a shopping mall to settle in and wait out the plague, setting up a nice little world for themselves.

Romero was very clever in choosing a mall for the setting of Dawn of the Dead. He was suspicious and skeptical of America’s growing consumer culture, a trajectory that took no rest during the 1970s. Filling a mall with zombies was very much a commentary on what that culture was doing to the country. As the zombies ramble with no purpose, save swarming and eating the living, so real society is equally oblivious to how it is being led astray — how they are forgoing real thought to mindless obeisance to popular culture. Human flesh, Adidas, rotting corpses, Orange Julius — the only difference in context is superficial if one has ever been to a shopping mall.

Romero’s survivors find the new existence they have carved out rudely interrupted by circumstance. If they hadn’t, Dawn of the Dead would have been boring. That’s how horror works. Comfort zones are punctured. As the chaos grows and consumes the plot, denouement is reached, and finally resolution. Without spoiling the film, not all of the four survive.

Of note, Dawn of the Dead was the first film in which special effects legend Tom Savini made his mark on horror. He also had a significant bit part in the film as a leader of a band of bikers that was trying to survive the zombie apocalypse, looking to take all they needed, by force, if necessary. This is one of the more significant films on Savini’s resume. There wasn’t a lot of budget to work with, as far as effects goes, which is why the majority of the zombies are just regular folks plastered with grey makeup, but where it was needed, the blood flowed with abandon. And what blood it is. It’s bright red, evocative of the early days of color film, but apparently that was a decision by Romero, who felt it was not necessary to burden such a fantastical film with any sort of gory realism. There’s no reason not to defer to his judgment.

Dawn of the Dead is a worthy sequel to Night of the Living Dead. It retains its humble roots in both budget and location. It strikes a great balance between cheese and seriousness, managing to achieve more depth in social commentary than most Hollywood films. Most importantly, Dawn of the Dead features a tense story filled with just the right amount of lulls and shocks to keep things surprising. A viewer will become invested in the fates of the main characters, rooting for them to do only the simplest of human endeavors — to survive.