John Milius must have a violence jones. That’s the only explanation for the films in which he’s played a pivotal part. He wrote Apocalypse Now, which turned war into hallucinatory spectacle, wrote and directed Red Dawn, considered by some at the time to be the most violent film ever made (no, it was not), and wrote and directed Conan the Barbarian, which really was the most violent film ever made at the time. I remember my first encounter with Conan the Barbarian. It was late one night when I was very young. I was supposed to be in bed, but from downstairs, I heard the television. Great clashes of bombastic music and the sounds of screaming warriors made their way up the steps, and I had to see what craziness the old man was watching. I should have known better.

I crouched at the top of the stairs and peeked through the railing at the TV, just in time to see Arnold Schwarzenegger cut off about fifty people’s heads with a fucking sword. Oh, no. There was blood everywhere. I ran back to my room and flew into bed. How I kept from crying out when I saw all that violence, I’ll never know. I was only six years old. That’s the last time I snuck out of bed to get a look at the television. Lesson learned.

Maybe it’s the distorted memory of childhood, but that scene I remember has been toned down quite a bit in every other cut of this movie I’ve seen since. I remember all sorts of necks spouting fake blood like a collection of gory fountains, but in this latest viewing, I counted only a single gusher. I don’t know what copy the Movie Channel was showing in 1983, but if they still have it, hidden away in the back of a closet somewhere, they should burn it. The cut that’s available now is violent enough.

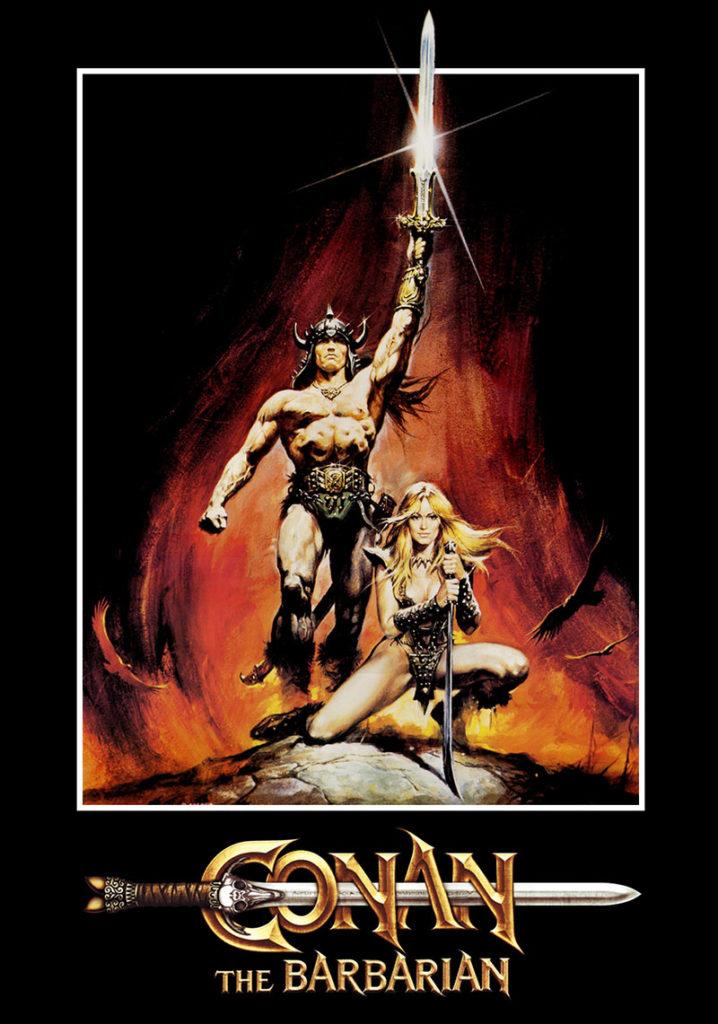

Arnold plays the titular Conan, taken  as a slave while just a boy and raised to be a ruthless killer. Conan’s only concern in life is roaming the unfamiliar lands of antiquity and killing as many people as he can. But he’s not a psychopath or anything. He’s an adventurer. For as bloody as this movie is, at heart it’s an adventure story. Conan and his band of adventurers travel to strange lands where people wear exotic clothes and hawk wares from distant walled cities. They walk through bazaars where the scents of spices and incense fill the air. They battle the monsters of myth and legend. And they see lots and lots of tits.

as a slave while just a boy and raised to be a ruthless killer. Conan’s only concern in life is roaming the unfamiliar lands of antiquity and killing as many people as he can. But he’s not a psychopath or anything. He’s an adventurer. For as bloody as this movie is, at heart it’s an adventure story. Conan and his band of adventurers travel to strange lands where people wear exotic clothes and hawk wares from distant walled cities. They walk through bazaars where the scents of spices and incense fill the air. They battle the monsters of myth and legend. And they see lots and lots of tits.

Buckets of blood and gratuitous nudity. It’s a total mystery how John Milius never became the biggest director of his day. What was missing?

Well, in Conan, it was probably the acting. James Earl Jones had a substantial role as the villain, and Mako danced well for his coin, but all of the other roles were filled by relative unknowns or bodybuilders. There was a paucity of dialogue in this film, which gives it a unique atmosphere, and one that works well, but I think this was by accident, rather than design. It couldn’t have taken Milius long to realize that just about everyone in his film could barely read a line. His solution? Go light with the words.

While the choreography and believability of the action sequences in this film are suffering over time, none of it feels any less exciting. Many other roaming adventure stories feel like they just lurch from set piece to set piece, and while Conan does have delineated scenes, the broader narrative tells a coherent story. Villain kills boy’s family, boy grows up into strong man, man vows revenge, man and his friends hunt villain. Along the way, if there are lost jewels and the hidden tombs of kings, then so be it. It’s all worth it just to get to the orgy scene, and not for the reason one might think. It’s in this scene that Milius’s film transforms from raucous vulgarity into poetry, when Basil Poledouris’s score comes to life and James Earl Jones turns into a snake. This scene made the film.

Many viewers could be turned off by either the one-dimensional nature of the film, or its overbearing masculinity. If one likes that kind of stuff, though, this film is a hoot. Hercules in New York made Arnold look like a joke, but this is the movie for which he was made. Correction: this is the movie for which Arnold made himself.