Wes Craven used to have one hell of a mean streak. I don’t mean personally. I never met the man, and have never read or heard anything to disparage his character. I’m referring to his methods as a filmmaker, specifically his earlier films.

The first film he wrote and directed, The Last House on the Left, is a brutal exploration of rape and murder, made during a time when filmmakers had a freer hand when it came to depicting brutality on screen. That film is an important part of the history of the horror genre, but liking it can feel like a moral failing at times. That’s how tough the subject matter was. His follow-up to that film was The Hills Have Eyes, from 1977.

The Carter family is on vacation. Patriarch Big Bob (Russ Grieve) is a retired police officer from the city of Cleveland, Ohio. He’s stuffed his family (wife, adult and teenage kids, a spouse, two dogs, and an infant grandson) into a station wagon and trailer and set off for a vacation in sunny Los Angeles. But along the way they decide, for very thin reasons, to seek out an old silver mine in the middle of the Nevada desert. They couldn’t have picked a worse place to go on a little adventure.  The area they chose is part of the Nellis Air Force Range, a huge expanse of barren wasteland where the Air Force is free to drop as many bombs as it wants. Nearby is the Nevada Test Site where, once upon a time, the United States exploded about 900 nuclear bombs in above and below ground tests. I’ve been to this part of the country before, and I can attest to its creepiness. It’s the perfect setting for a horror film, even before the film’s protagonists encounter anything frightening.

The area they chose is part of the Nellis Air Force Range, a huge expanse of barren wasteland where the Air Force is free to drop as many bombs as it wants. Nearby is the Nevada Test Site where, once upon a time, the United States exploded about 900 nuclear bombs in above and below ground tests. I’ve been to this part of the country before, and I can attest to its creepiness. It’s the perfect setting for a horror film, even before the film’s protagonists encounter anything frightening.

Which they do!

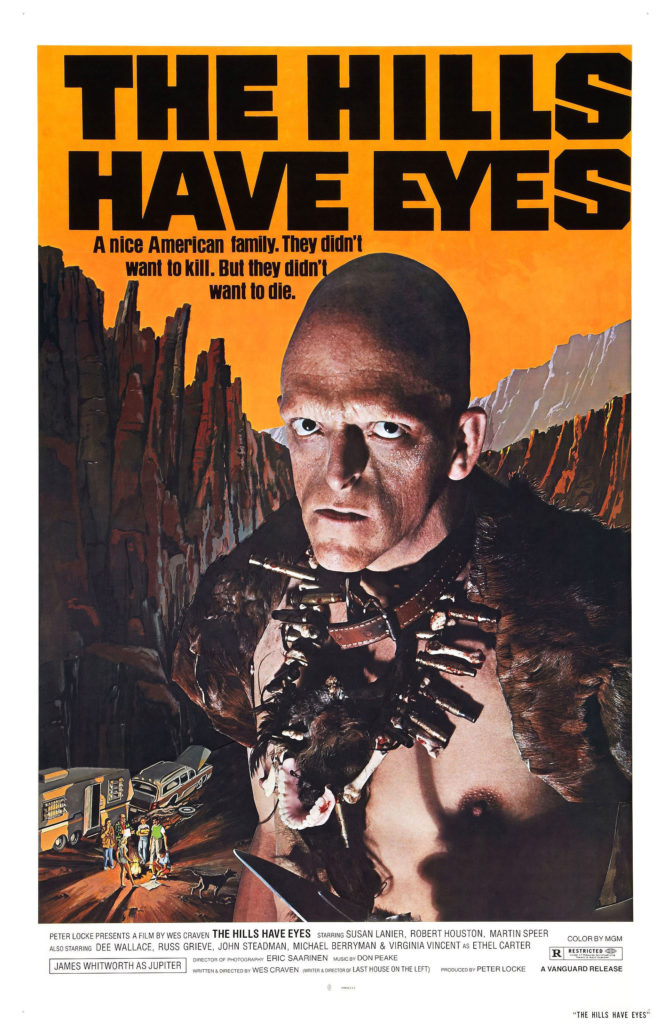

While searching for the mine, Big Bob runs the station wagon off a remote dirt road and breaks the rear axle. The Carters are stranded. But they aren’t the only family around. It turns out there’s a family of cannibals living up in the surrounding hills, and it’s been a while since they had a decent meal. They’re led by Papa Jupiter (James Whitorth), an insanely violent and bloodthirsty man. He dispatches his sons Mars (Lance Gordon), Mercury (Arthur King), and Pluto (horror icon Michael Berryman) to attack the family and bring back some good eats. What follows is another study in violence as brought to viewers by Wes Craven.

The film is broken up into multiple segments where members of the Carter family are attacked by the cannibals, but there’s one sequence in particular that will stick with viewers. After the sun has set and terrible, bad, no good things have already happened to Big Bob, the family is set upon by Pluto and Mars. Craven took what he learned in his previous film and applied it here, crafting a disturbing scene of violence, rape, and kidnapping. It’s the type of horror scene that is not designed to frighten, but rather to sicken. There’s nothing supernatural or otherworldly about Papa Jupiter and his kids. They are violent savages, and this attack plays out closer to reality than what many viewers would expect. The film marches to a frenetic denouement and an ending that left me gasping for air.

The Hills Have Eyes, in many ways, makes me question the purpose of horror films. Off the top of my head, it seems the purpose is to create jolts of adrenaline in the viewer. Under the right circumstances, fright can be an enjoyable experience. If that weren’t true, there would be no such things as horror movies or carnival fun houses. But with this film, Craven brought a heaviness that is hard to enjoy. This is a well-crafted film, with fine pace and storytelling, and even some good performances here and there. But to say it’s a pleasant experience would be disingenuous. It doesn’t reach the torturous effort it takes to get through something like Eraserhead, but it’s far from fun. The Hills Have Eyes is essential viewing for horror film buffs and students of cinema. Just remember that it’s a sick little exercise.